OK I'll bite :-)

Off the top of my head, here are 6 reasons (in somewhat random order) why a heterogeneous agent model allows you do more than "just starting from the MPC>>0 and then going forward from there":

(I'm sure there are many others -- what else?)

Off the top of my head, here are 6 reasons (in somewhat random order) why a heterogeneous agent model allows you do more than "just starting from the MPC>>0 and then going forward from there":

(I'm sure there are many others -- what else?)

https://twitter.com/JWMason1/status/1410811618481614851

1. The world is dynamic: future income affects current consumption and current income affects future consumption. This obviously matters for policy.

HA models provide a framework for this, see eg the nice exposition by @a_auclert Rognlie @ludwigstraub web.stanford.edu/~aauclert/ikc.…

HA models provide a framework for this, see eg the nice exposition by @a_auclert Rognlie @ludwigstraub web.stanford.edu/~aauclert/ikc.…

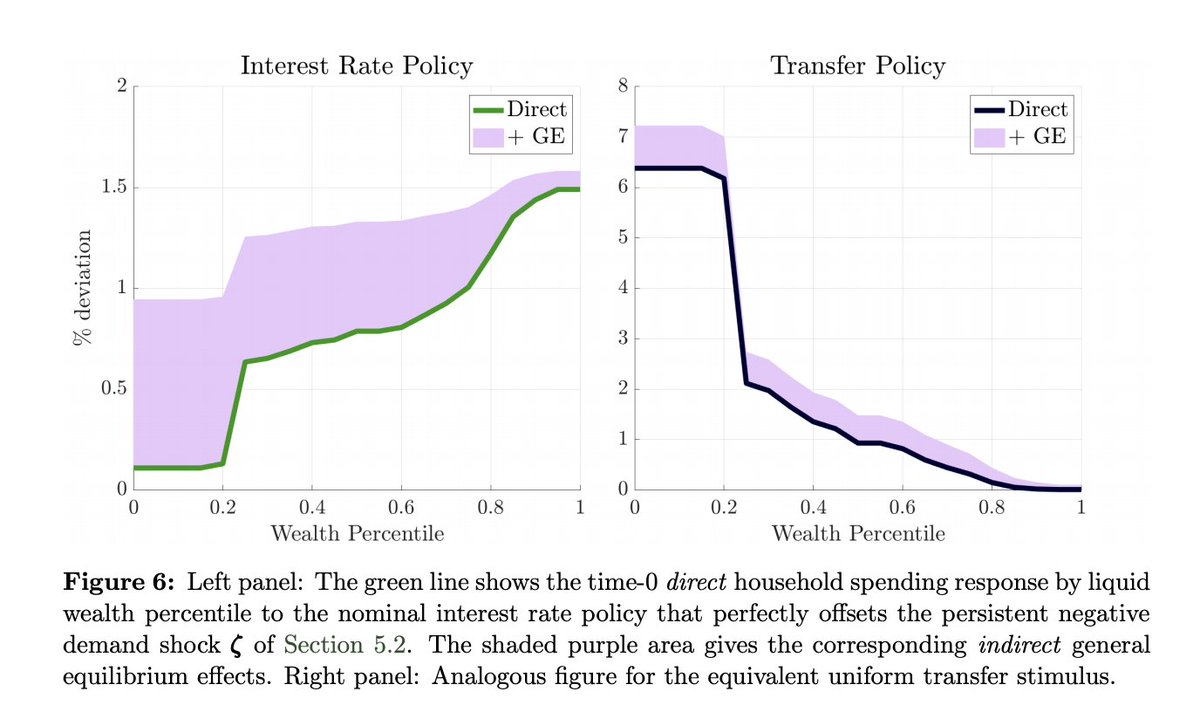

2. We may want to compare different policy options within the same framework, e.g. how does fiscal policy compare to monetary policy?

Again HA models provide a framework for this, see e.g. this nice recent paper by @ChristianKWolf scholar.princeton.edu/sites/default/…

Again HA models provide a framework for this, see e.g. this nice recent paper by @ChristianKWolf scholar.princeton.edu/sites/default/…

3. We may want to think about the distributional and welfare effects of monetary and fiscal policy. Again HA models allow you to do this, see e.g. @glviolante ecb.europa.eu/pub/conference… and ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/scpwps…

4. Q: how do we actually know how sensitive consumption is to current income?

A: mostly from micro evidence see e.g. the work of @ProfJAParker @p_ganong @pascaljnoel @Farrell_Diana @FionaGreigDC @AndreasFagereng @BlomhoffHolm @GNatvik @LorenzKueng @pilossopher @THEdanjlewis

A: mostly from micro evidence see e.g. the work of @ProfJAParker @p_ganong @pascaljnoel @Farrell_Diana @FionaGreigDC @AndreasFagereng @BlomhoffHolm @GNatvik @LorenzKueng @pilossopher @THEdanjlewis

4. (continued): would it perhaps be useful to have a framework that can connect to this micro evidence?

I happen to think so. HA models can do this. I struggle to see how the framework @JWMason1's envisions does this.

I happen to think so. HA models can do this. I struggle to see how the framework @JWMason1's envisions does this.

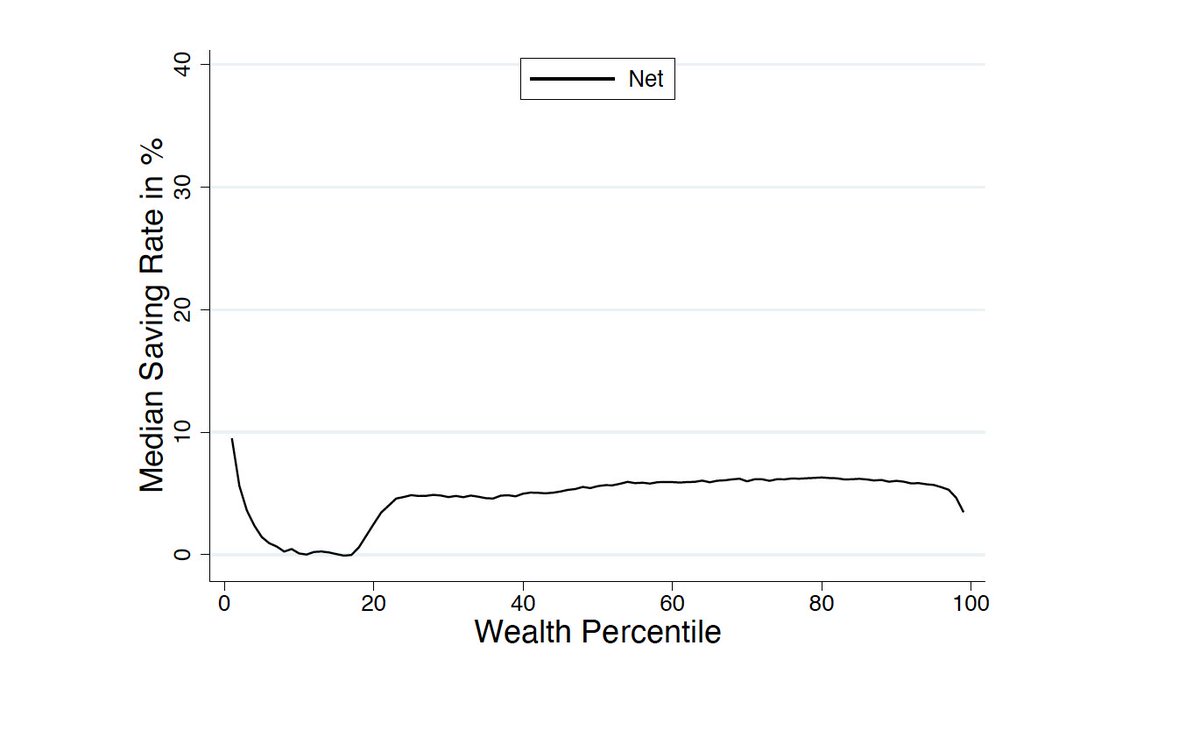

5. Related, I'd say there is really no such thing as *the* aggregate MPC. Instead there's a distribution of micro-level MPCs.

HA models feature exactly such a distribution and can connect with empirical evidence on it, see eg @GregWKaplan and @glviolante

HA models feature exactly such a distribution and can connect with empirical evidence on it, see eg @GregWKaplan and @glviolante

6. There are lots of different potential transmission mechanisms of monetary and fiscal policy.

HA models provide an integrated organizing framework to think through these (and their distributional and dynamic effects), see e.g. benjaminmoll.com/research_agend…

HA models provide an integrated organizing framework to think through these (and their distributional and dynamic effects), see e.g. benjaminmoll.com/research_agend…

OK let me stop here. What other reasons did I miss?

I should also add: obviously I'm not trying to say "all is amazing in macro."

And there are a number of arguments in @JWMason1's piece I'm quite sympathetic to, eg putting more emphasis on national accounting in PhD teaching

I should also add: obviously I'm not trying to say "all is amazing in macro."

And there are a number of arguments in @JWMason1's piece I'm quite sympathetic to, eg putting more emphasis on national accounting in PhD teaching

(p.s. I missed yesterday's EconFIP panel because it was a bit late in London so don't know what was discussed there)

Late addition:

7. Distribution may matter for aggregate MPC & dynamics more generally

Note: these distributional state vars can be v different from "inequality" e.g. distribution of savings from mortgage refinancing here arlene-wong.com/s/refinance.pdf

Thx @JohnHCochrane for nudging

7. Distribution may matter for aggregate MPC & dynamics more generally

Note: these distributional state vars can be v different from "inequality" e.g. distribution of savings from mortgage refinancing here arlene-wong.com/s/refinance.pdf

Thx @JohnHCochrane for nudging

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh