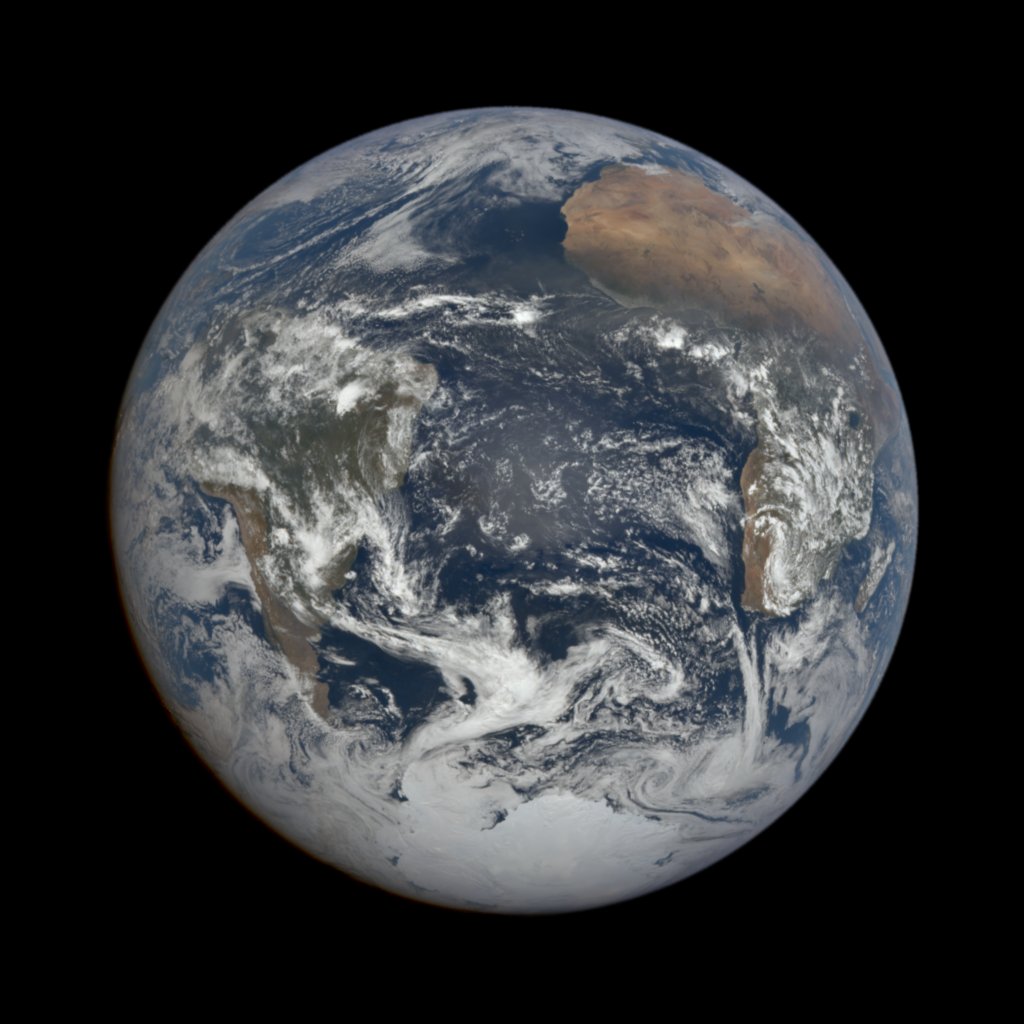

Preliminary reports suggest #HurricaneIda is the fifth-strongest storm ever to make landfall in the continental U.S. earthobservatory.nasa.gov/images/148767/…

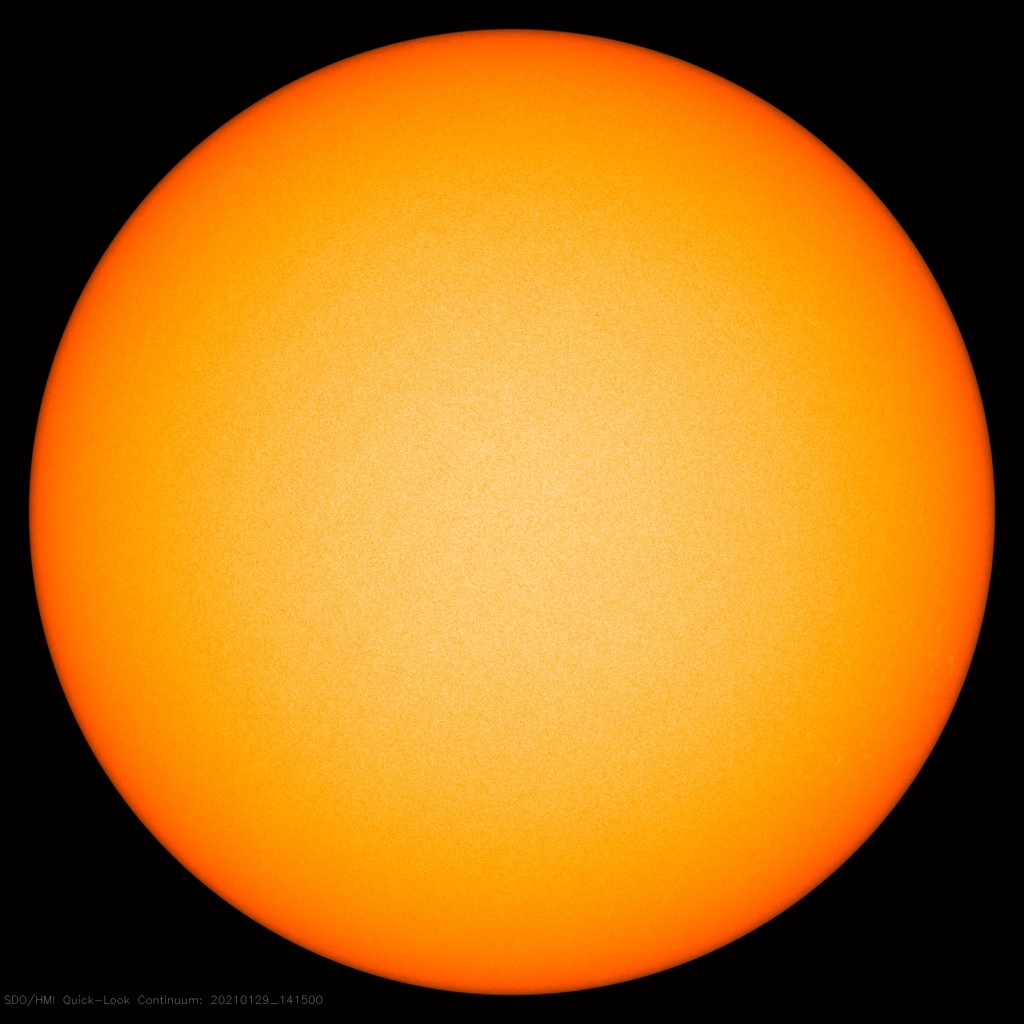

“For me, the most compelling aspect of Ida was its rapid intensification up to landfall,” said Scott Braun, a scientist who specializes in hurricanes at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center.

More than 1 million customers in Louisiana had reportedly lost power by midday on August 30. Another 100,000 customers lost electricity in Mississippi and 12,000 in Alabama.

The storm lingered over southern Louisiana for most of August 29, dropping flood-provoking rainfall before moving north and east into Mississippi and Alabama on August 30.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh