1/

Why is metformin associated with lactic acidosis? Do we need to routinely stop metformin when admitting patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM) to the hospital?

Let's explore these questions by looking at the history of metformin in the following #histmed #tweetorial.

Why is metformin associated with lactic acidosis? Do we need to routinely stop metformin when admitting patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM) to the hospital?

Let's explore these questions by looking at the history of metformin in the following #histmed #tweetorial.

2/

Metformin, a biguanide, works by decreasing hepatic glucose production and increasing insulin sensitivity.

It is a first-line therapy in T2DM because it's inexpensive, well-tolerated, helps with weight loss, and has very low risk of hypoglycemia.

ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/P…

Metformin, a biguanide, works by decreasing hepatic glucose production and increasing insulin sensitivity.

It is a first-line therapy in T2DM because it's inexpensive, well-tolerated, helps with weight loss, and has very low risk of hypoglycemia.

ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/P…

3/

Metformin derives from galega officinalis, a plant long used in European folk medicine.

First synthesized in the 1920s, metformin was shown to lower blood glucose in rabbits but it was soon forgotten and eclipsed by the discovery insulin.

Metformin derives from galega officinalis, a plant long used in European folk medicine.

First synthesized in the 1920s, metformin was shown to lower blood glucose in rabbits but it was soon forgotten and eclipsed by the discovery insulin.

4/

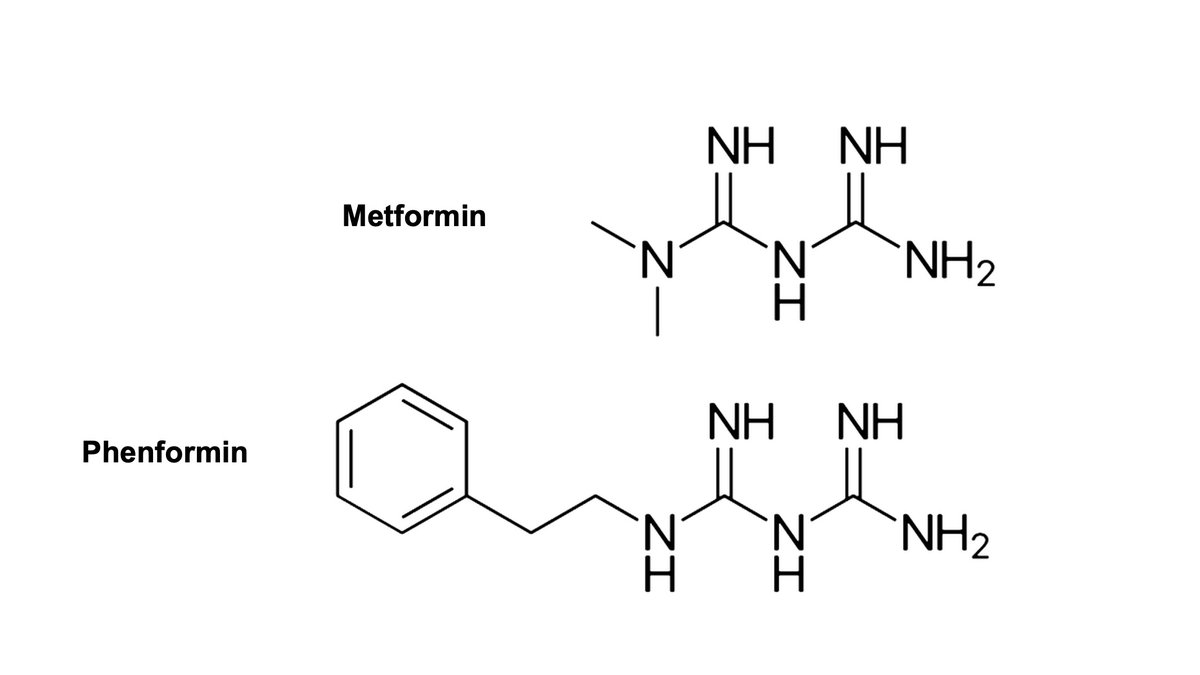

Interest in the biguanides returned in the 1950s, but metformin was again overshadowed, this time by phenformin, which had more potent blood glucose lowering effects.

Interest in the biguanides returned in the 1950s, but metformin was again overshadowed, this time by phenformin, which had more potent blood glucose lowering effects.

5/

While phenformin was quite successful at lowering blood glucose levels it would ultimately be pulled from the market in 1970s due to its association with severe lactic acidosis, which was often fatal.

jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/…

While phenformin was quite successful at lowering blood glucose levels it would ultimately be pulled from the market in 1970s due to its association with severe lactic acidosis, which was often fatal.

jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/…

6/

Why did phenformin lead to such severe lactic acidosis?

It came down to 3 factors:

1️⃣ The general mechanism of action of biguanides.

2️⃣ Phenformin's size and structure.

3️⃣ Phenformin's metabolism.

Why did phenformin lead to such severe lactic acidosis?

It came down to 3 factors:

1️⃣ The general mechanism of action of biguanides.

2️⃣ Phenformin's size and structure.

3️⃣ Phenformin's metabolism.

7/

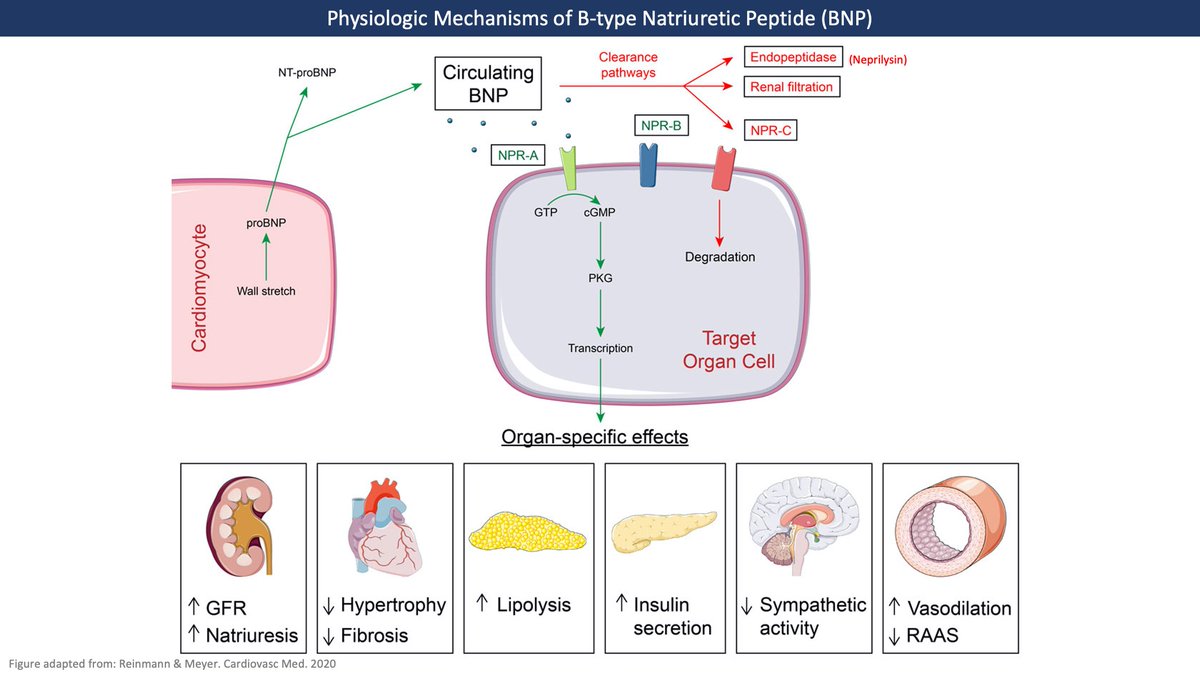

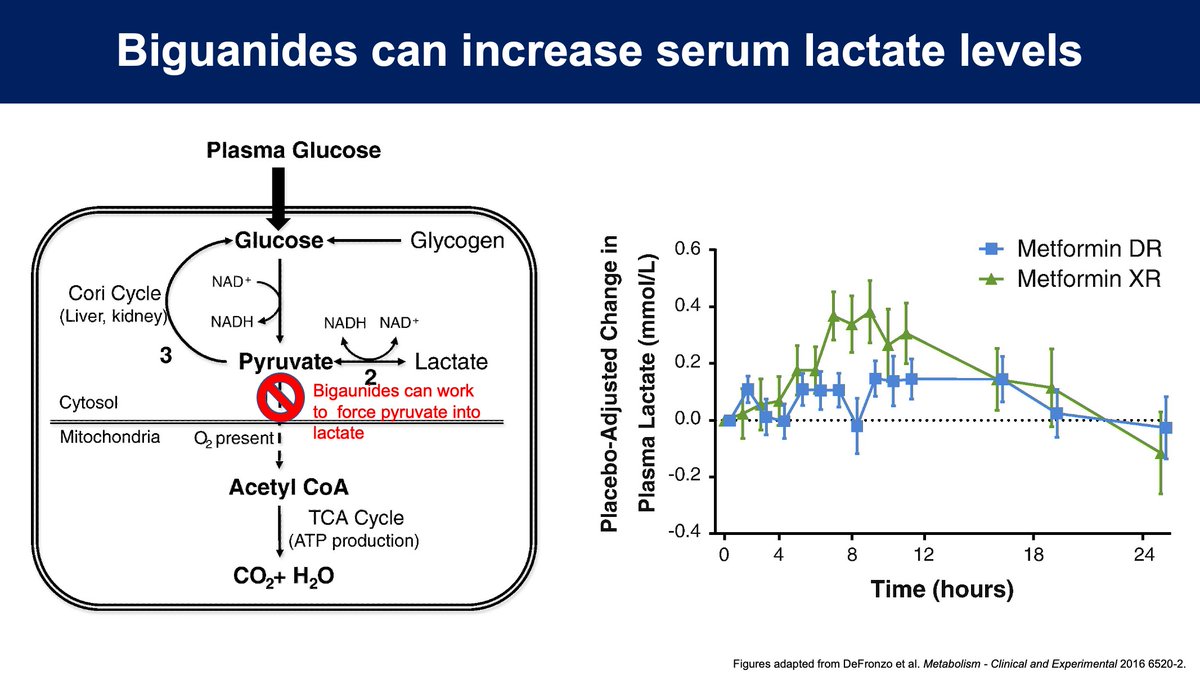

1️⃣ While the mechanism of biguanides isn't fully understood, they do inhibit pyruvate dehydrogenase and mitochondrial electron transport, which can force anaerobic metabolism.

As a result, all biguanides can cause serum lactate levels to rise.

pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26773926/

1️⃣ While the mechanism of biguanides isn't fully understood, they do inhibit pyruvate dehydrogenase and mitochondrial electron transport, which can force anaerobic metabolism.

As a result, all biguanides can cause serum lactate levels to rise.

pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26773926/

8/

2️⃣ While all biguanides ⬆️ lactate production, the body is usually able to handle this load without issue.

Phenformin, however, has a large lipophilic side chain which potently binds to mitochondrial membrane, causing excess lactate production.

pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9625516/

2️⃣ While all biguanides ⬆️ lactate production, the body is usually able to handle this load without issue.

Phenformin, however, has a large lipophilic side chain which potently binds to mitochondrial membrane, causing excess lactate production.

pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9625516/

9/

3️⃣ The last reason phenformin leads to lactic acidosis has to do with its 10-15h half-life, which can be even longer with renal insufficiency.

Additionally ~10% of people have defects in phenformin hydroxylation which can further increase levels .

pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7250534/

3️⃣ The last reason phenformin leads to lactic acidosis has to do with its 10-15h half-life, which can be even longer with renal insufficiency.

Additionally ~10% of people have defects in phenformin hydroxylation which can further increase levels .

pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7250534/

10/

The issues with phenformin led to understandable reluctance to use metformin, which wasn't approved for use in the US until the 1990s even though it had been used safely in other countries since the 50s.

But does metformin have the same risk of lactic acidosis?

The issues with phenformin led to understandable reluctance to use metformin, which wasn't approved for use in the US until the 1990s even though it had been used safely in other countries since the 50s.

But does metformin have the same risk of lactic acidosis?

11/

Unlike phenformin, metformin has a relatively short half-life as it is cleared through the kidneys without even being metabolized.

Metformin also binds mitochondrial membranes less potently and thus elevates lactate levels to significantly less effect than phenformin does.

Unlike phenformin, metformin has a relatively short half-life as it is cleared through the kidneys without even being metabolized.

Metformin also binds mitochondrial membranes less potently and thus elevates lactate levels to significantly less effect than phenformin does.

12/

While metformin does elevate serum lactate levels, the kidneys and liver are usually able to handle the increased lactate load (see tweet 8). As a result, metformin-associated lactic acidosis (MALA) is extremely rare without underlying hepatic or renal insufficiency (GFR <30)

While metformin does elevate serum lactate levels, the kidneys and liver are usually able to handle the increased lactate load (see tweet 8). As a result, metformin-associated lactic acidosis (MALA) is extremely rare without underlying hepatic or renal insufficiency (GFR <30)

13/

Despite decades of use, the data we have about MALA largely comes from case reports.

In almost all cases there are other conditions that themselves can lead to lactic acidosis including heart failure, sepsis, and kidney failure.

pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24326619/

Despite decades of use, the data we have about MALA largely comes from case reports.

In almost all cases there are other conditions that themselves can lead to lactic acidosis including heart failure, sepsis, and kidney failure.

pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24326619/

14/ The most comprehensive review of the data comes from a 2010 Cochrane review which analyzed 347 studies and found no cases of lactic acidosis despite looking at > 70,000 patient-years of metformin use.

cochrane.org/CD002967/ENDOC…

cochrane.org/CD002967/ENDOC…

15/

So, is metformin safe to use in hospitalized patients?

Many are trained to reflexively stop metformin on admission largely due to concerns about lactic acidosis. Do we need to universally stop it and deprive patients of an effective medication?

So, is metformin safe to use in hospitalized patients?

Many are trained to reflexively stop metformin on admission largely due to concerns about lactic acidosis. Do we need to universally stop it and deprive patients of an effective medication?

16/

The answer, of course, is it depends.

As with MALA, the data for metformin use in the hospital are poor but given the rarity of MALA we may not need to hold it as often as we do and should individualize care.

The answer, of course, is it depends.

As with MALA, the data for metformin use in the hospital are poor but given the rarity of MALA we may not need to hold it as often as we do and should individualize care.

17/

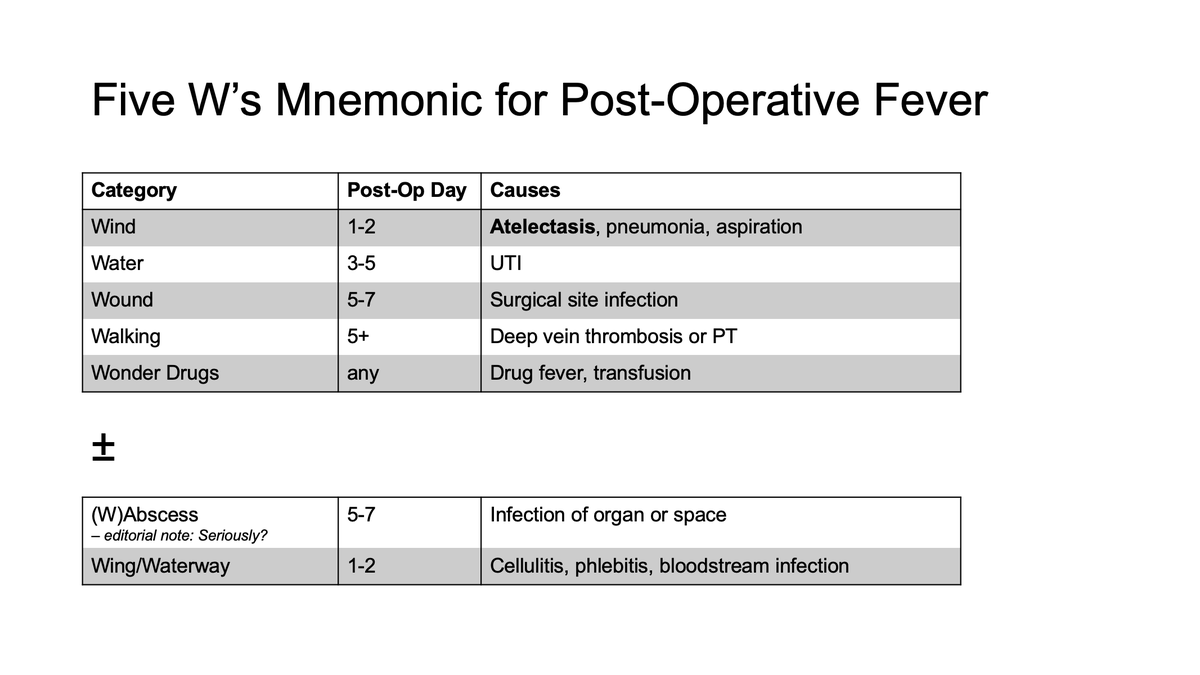

Obviously if there is renal impairment, especially GFR <30, another lactate-producing condition, or other obvious contraindication, metformin should be held.

But once things improve or if the patient is stable, it's probably okay to continue the metformin.

Obviously if there is renal impairment, especially GFR <30, another lactate-producing condition, or other obvious contraindication, metformin should be held.

But once things improve or if the patient is stable, it's probably okay to continue the metformin.

18/ In summary:

💊 Metformin is an effective first-line therapy for T2DM

💊 Phenformin is a biguanide historically associated with severe lactic acidosis

💊 Metformin can also cause lactic acidosis but this is very rare those with normal kidney and liver function.

💊 Metformin is an effective first-line therapy for T2DM

💊 Phenformin is a biguanide historically associated with severe lactic acidosis

💊 Metformin can also cause lactic acidosis but this is very rare those with normal kidney and liver function.

For more discussion on when to continue metformin or otherT2DM meds in hospitalized patients check out this podcast @SatyaPatelMD and I helped to produce for @COREIMpodcast!

https://twitter.com/COREIMpodcast/status/1448237044430512132?s=20

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh