The name of God in the Quran is Aḷḷāh, that much is clear. We also know that the Quran explicitly equates its God with the God the Christians and Jews follow. Today Arabic Christian and Jews alike will indeed call their God that. But where does this name come from? 🧵

It is frequently (and not unreasonably) assumed that Aḷḷāh is a contraction of the definite article al- "the" + ʾilāh "deity". And this is indeed likely its origin, but it is not without its problems. This loss of hamzah and kasrah (and addition of velarization) is irregular.

In Classical Arabic, the expected outcome of al-+ ʾilāh would simply be al-ʾilāh, not Aḷḷāh. So while its etymology might be "The God", the name does not mean "The God", just like "Peter" to an English speaker would not mean "stone".

en.wiktionary.org/wiki/%CF%80%CE…

en.wiktionary.org/wiki/%CF%80%CE…

In an ingenious article by David Testen, he writes an *extremely* specifically conditioned sound change (as is his wont) to account for the contraction al-ʾilāh > Aḷḷāh, and points out that a similar contraction could also account for ʾunās "people", but an-nās "the people".

This could indeed mostly regularly account for Aḷḷāh and an-nās, although there's the unexplained appearance of emphasis of the ḷ in the divine name which remains unexplained.

Importantly: Aḷḷāh is the *name* of God, not the way of saying "The God" (which would be al-ʾilāh)

Importantly: Aḷḷāh is the *name* of God, not the way of saying "The God" (which would be al-ʾilāh)

As I said, Jews and Christians call their God Aḷḷāh today, and that's been true since Medieval times.

But what about the uses of al-ʾilāh and aḷḷāh before Islam? Was Aḷḷāh used for the Jewish and Christian God? What was the use of al-ʾilāh?

But what about the uses of al-ʾilāh and aḷḷāh before Islam? Was Aḷḷāh used for the Jewish and Christian God? What was the use of al-ʾilāh?

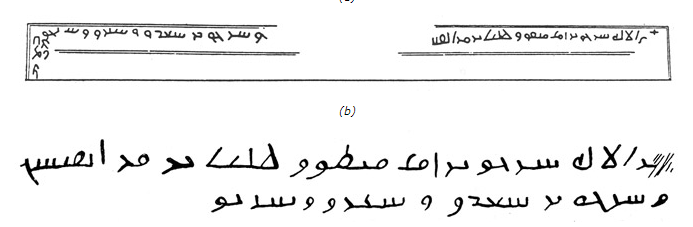

In recent years, more and more Christian Arabic inscriptions from before Islam have become available to us. And whenever they invoke the Christian God, he has a single name and it is *not* Aḷḷāh. Instead, they consistently call him al-ʾIlāh

The name occurs in the formula ḏakara al-ʾilāh "May The God remember". Al-Jallad has recently published another case of such an inscription, which is likely actually be from the Early Islamic period!

onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/aa…

onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/aa…

So far, there is not a single example where a Christian calls their Christian God Aḷḷāh. Always al-ʾilāh.

So what about Aḷḷāh? is it not around at all before Islam? As a matter of fact it is attested with some frequency!

So what about Aḷḷāh? is it not around at all before Islam? As a matter of fact it is attested with some frequency!

Tradition tells us that the Prophet Muhammad's own father was called ʿAbd Aḷḷāh 'servant of Aḷḷāh', which certainly suggests (if historical) that the name was around. And indeed exactly that name along with other Aḷḷāhphoric names are found given to Nabataean Arabs.

1. zbdw br zyd ʾlhy /zaydu ʾAllāhi/

2. ḥb ʾlhy /ḥuḅḅu ʾAllāhi/

3. ʿbd ʾlhy /ʿabdu ʾAllāhi/

4. šʿd ʾlhy /saʿdu ʾAllāhi/

But Nabataeans could just as easily have different Gods in this position, thus we find names like ʿbdmnwty /ʿAbdu Manōti/ "servant of Manāt"!

2. ḥb ʾlhy /ḥuḅḅu ʾAllāhi/

3. ʿbd ʾlhy /ʿabdu ʾAllāhi/

4. šʿd ʾlhy /saʿdu ʾAllāhi/

But Nabataeans could just as easily have different Gods in this position, thus we find names like ʿbdmnwty /ʿAbdu Manōti/ "servant of Manāt"!

Clearly then the name ʿAbd Aḷḷāh is appearing in a pagan context, and this is even clearer ni the En Avdat inscription, which is dedicated to the deified Nabataean King Obodas, but the author of the inscription calls himself grmʾlhy /ǧaramu ʾAllāhi/.

There is nothing in these Nabataean inscriptions to suggest that Aḷḷāh is the same god as the god of the Jews and Christians, and it's difficult to evaluate his position in the pantheons. While it's a common deity in theophoric names, he's (I believe) never invoked.

This is different for the writers the Arabic of Safaitic inscriptions. In these inscriptions, Aḷḷāh is occasionally invoked, but always besides other deities. And the other deities are invoked MUCH more than Aḷḷāh ever is.

(Statistic from: academia.edu/45498003/Al_Ja… )

(Statistic from: academia.edu/45498003/Al_Ja… )

In other words, Allāt ((ʾ)lt) of Quranic fame (quran.com/53/19) is invoked 36 times more often (!) than Allāh ((ʾ)lh).

This relative lack of popularity does not really suggest that he was in any way a central figure in the pantheon.

This relative lack of popularity does not really suggest that he was in any way a central figure in the pantheon.

Based on the data available, this does not seem to be a case of Quranic "mušrikūn" who associate other deities along with the primary monotheistic God of the Old Testament. If anything, they seem to associate Aḷḷāh with Allāt rather than vice-versa.

Nothing in the 41 attestations mentioned give any indication that the Safaitic Aḷḷāh was understood to be the Jewish God (many of inscriptions are likely pre-Christian so he can't be associated with the Christian God yet 😁).

To recapitulate: 6th century Christian Arabic speakers do *not* call their God Aḷḷāh, but al-ʾilāh.

Pagan Arabic speakers around 1st c. BCE-1st c. CE know a minor deity in their pantheon named Aḷḷāh, and it is unclear if they equated him to the Jewish God.

Pagan Arabic speakers around 1st c. BCE-1st c. CE know a minor deity in their pantheon named Aḷḷāh, and it is unclear if they equated him to the Jewish God.

So, is the Quran the first one to associate the name Aḷḷāh with a monotheistic deity? No, in recent years more and more monotheistic Arabic inscriptions, probably from the 6th century have been showing up. around the Hijaz that seem to invoke Aḷḷāh.

For example, the really exciting ʿAbd Šams inscription has the invocation بسمك اللهم bi-smi-ka Aḷḷāhumma "In Your Name, O Aḷḷāh", which the Islamic tradition indeed remembers as an invocation of Aḷḷāh before Islam!

https://twitter.com/shahanSean/status/1003055345026195457

Of course, this inscription still does not tell us with certainty that this Aḷḷāh is being associated with the Christian or Jewish God, but it clearly leads up to the later Hijazi association of Aḷḷāh as the central deity.

In an inscription in the Ancient South Arabian cursive script Aḷḷāh is invoked, clearly equated to the South Arabian Raḥmān, who was certainly considered to be the Christian and Jewish God. This equation is of course also seen in the Quranic basmalah.

academia.edu/43388891/Al_Ja…

academia.edu/43388891/Al_Ja…

So to sum up:

1. Aḷḷāh might come from al-ʾilāh "the God" but it is not the SAME as saying "The God". It is a name.

2. Christian before Islām call The God al-ʾilāh

3. Pagans around the year zero know a pagan God called Aḷḷāh

4. At some point before Islam these merge into one.

1. Aḷḷāh might come from al-ʾilāh "the God" but it is not the SAME as saying "The God". It is a name.

2. Christian before Islām call The God al-ʾilāh

3. Pagans around the year zero know a pagan God called Aḷḷāh

4. At some point before Islam these merge into one.

If you enjoyed this thread and want me to do more of it, please consider buying me a coffee.

ko-fi.com/phdnix.

If you want to support me in a more integral way, you can become a patron on Patreon!

patreon.com/PhDniX

ko-fi.com/phdnix.

If you want to support me in a more integral way, you can become a patron on Patreon!

patreon.com/PhDniX

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh