Fall was meant to mark the beginning of the end of the labor shortage that has held back the economic recovery. Instead, the labor force *shrank* in September. What happened?

Thread below, story here:

nytimes.com/2021/10/19/bus…

Thread below, story here:

nytimes.com/2021/10/19/bus…

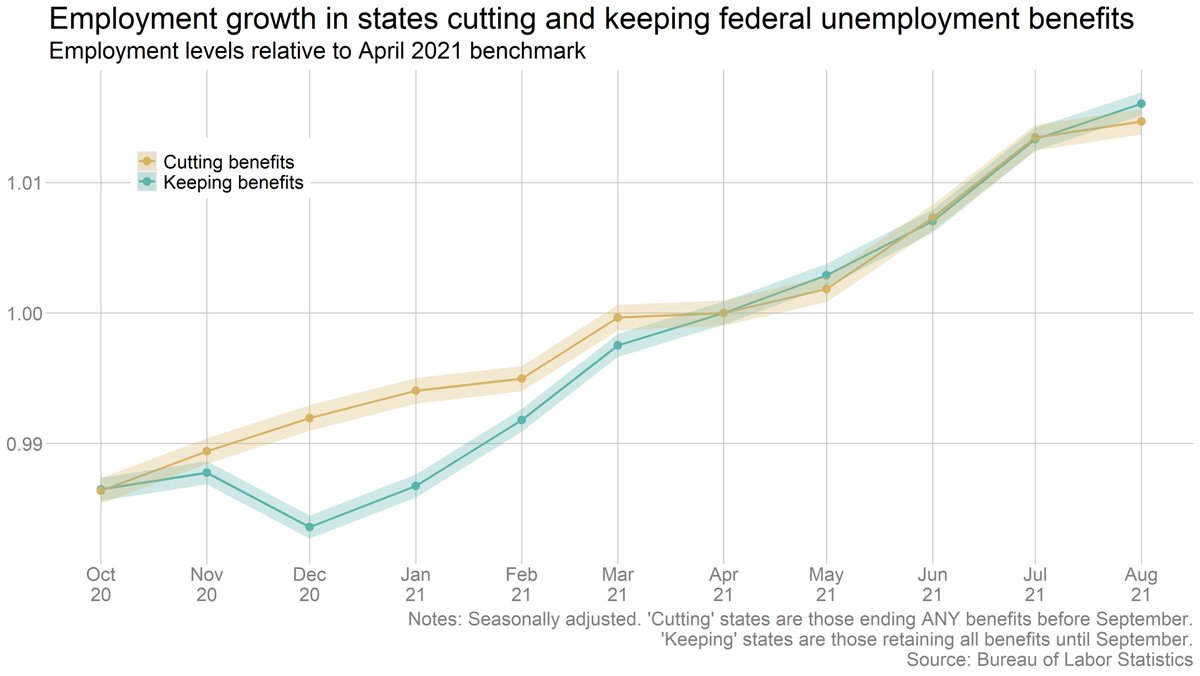

Last spring, many people blamed extra unemployment benefits for keeping people out of work. Some GOP politicians continue to make that claim. But the evidence doesn't support it: Data from states that ended benefits early shows that any impact was small.

nytimes.com/2021/08/20/bus…

nytimes.com/2021/08/20/bus…

Many progressives have argued there is a "shortage of wages, not of workers." But pay has been rising rapidly, especially in lower-wage industries, and the hiring difficulties aren't limited to low-wage sectors.

(Note that this is very different from the aftermath of the last recession, when many businesses also complained they couldn't find workers but were not raising pay.)

So what does explain the slow return of workers? A confluence of factors. Starting, of course, with the virus itself, which is still making some people reluctant to work, especially since the rise of the Delta variant.

Many workers also still cite child care as a big factor. Schools have reopened, but with constant threats of quarantines, and child care is hard to find (or afford) because of a labor crisis in that sector, as @clairecm has written:

nytimes.com/2021/09/21/ups…

nytimes.com/2021/09/21/ups…

I have also heard from a lot of people that the pandemic changed their priorities around work -- either making them want to work less, or to change industries, or to demand better conditions. This is hard to measure, but I do believe it's real.

.@byHeatherLong wrote arguably the definitive piece about this attitude back in May:

washingtonpost.com/business/2021/…

washingtonpost.com/business/2021/…

Here's the thing, though: People still have to pay rent. Fear of Covid, child care issues, a reassessment of work -- these are all real reasons to be reluctant to return to work (or to certain kinds of jobs). But most people don't have the luxury to just decide not to work.

Which brings us to the other big factor: savings. As @DLeonhardt wrote earlier this week, Americans are collectively sitting on trillions more in savings than they were before the pandemic.

nytimes.com/2021/10/18/bri…

nytimes.com/2021/10/18/bri…

Now, the "collectively" in that sentence is doing a lot of work -- a lot of that money is held by the rich. But it isn't just them. The combination of government aid and reduced spending during the pandemic has boosted savings across the income spectrum.

https://twitter.com/p_ganong/status/1450053587946688514

Now, as @FionaGreigDC has noted, median savings among low-income households is still only ~$1,000. Most people still need to work, and soon. But for some households, it isn't quite as urgent now as it usually is.

https://twitter.com/FionaGreigDC/status/1450055402557788164

(To be clear: These are averages. There are absolutely people whose savings were wiped out during the pandemic, and there are many, many others whose savings are still too meager to give them any flexibility.)

Add it all up, and we're in a moment when many people both have more reason than usual to be choosy about where/when/how they work, and more wherewithal to be choosy. They also know they have options -- they're seeing the same "labor shortage" stories as everyone else.

As @BetseyStevenson told me: "It’s like the whole country is in some kind of union renegotiation... I don’t know who’s going to win in this bargaining that’s going on right now, but right now it seems like workers have the upper hand.”

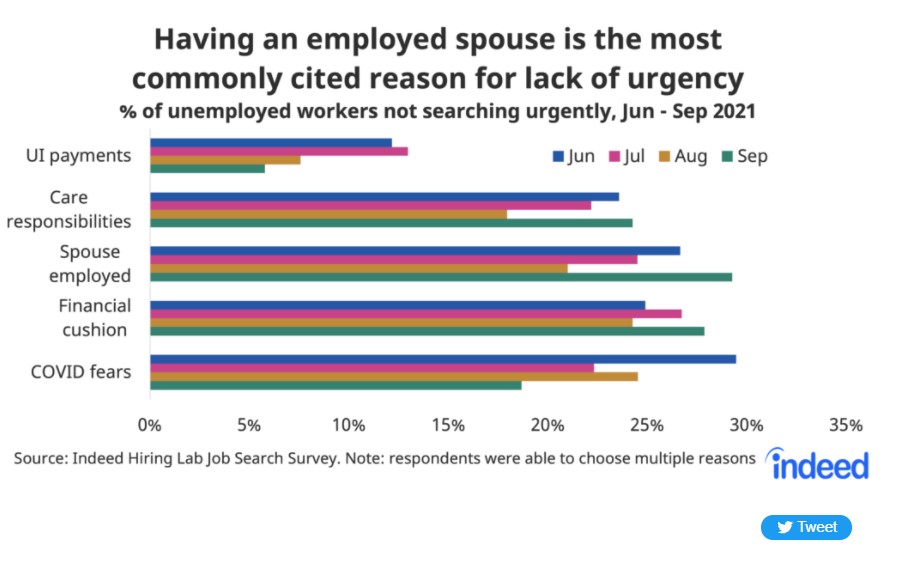

This survey from @indeed supports this idea. Most common reasons unemployed workers give for not searching "urgently" are related to other forms of support (spouse's job, financial cushion). But care responsibilities, Covid still up there.

hiringlab.org/2021/10/12/job…

hiringlab.org/2021/10/12/job…

But it's also worth asking how hard *companies* are searching. Many have found ways to get by with fewer workers, in some cases by putting the burden on customers (think long wait times, worse service). That can be pretty profitable, at least as long as customers put up with it.

As @juliaonjobs put it: “They’re making a lot of profits in part because they’re saving on labor costs, and the question is how long can that go on."

So there's a standoff: Workers are holding out until their savings disappear. Businesses are holding out until their customers disappear. Maybe one or the other will give, or maybe there will be a meeting in the middle. (Or, realistically, some of all three.)

Final note: Many workers I've spoken to have found ways to make ends meet outside of traditional jobs, via gig work, entrepreneurship (way up in Covid!), reduced spending, etc.

Will that last? Hard to say. But this is not a binary choice.

nytimes.com/2021/08/19/bus…

Will that last? Hard to say. But this is not a binary choice.

nytimes.com/2021/08/19/bus…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh