It can be useful for teachers to have a mental model of the main processes involved in learning.

Here's mine (thread):

↓

Here's mine (thread):

↓

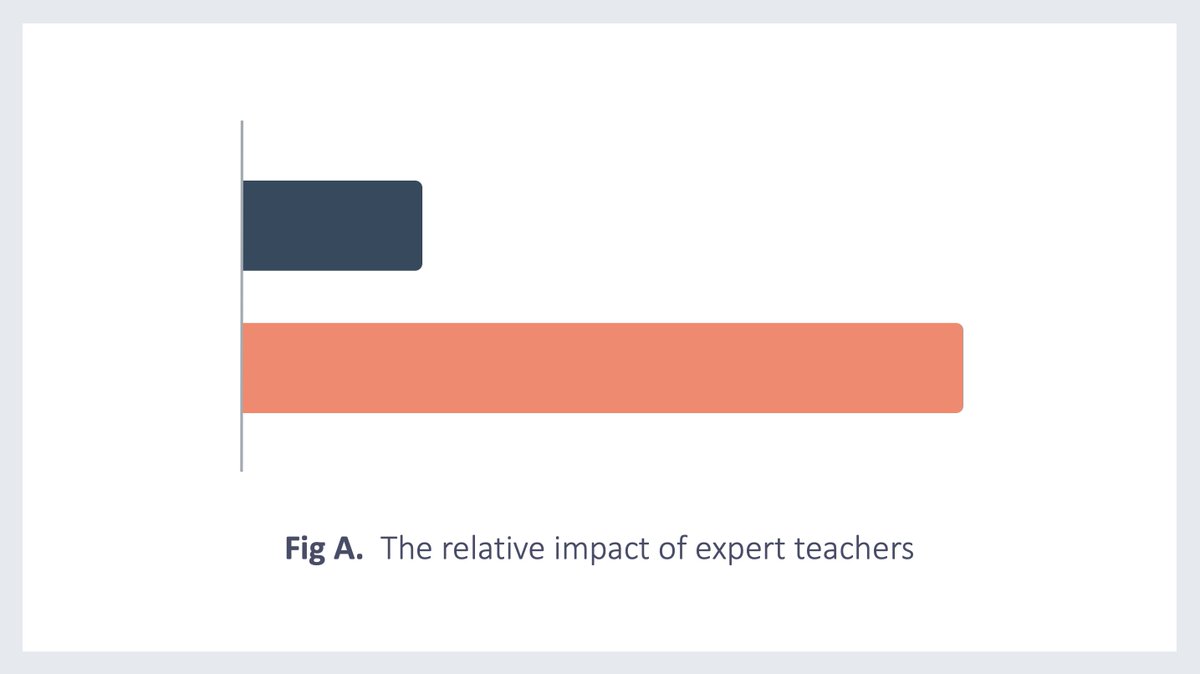

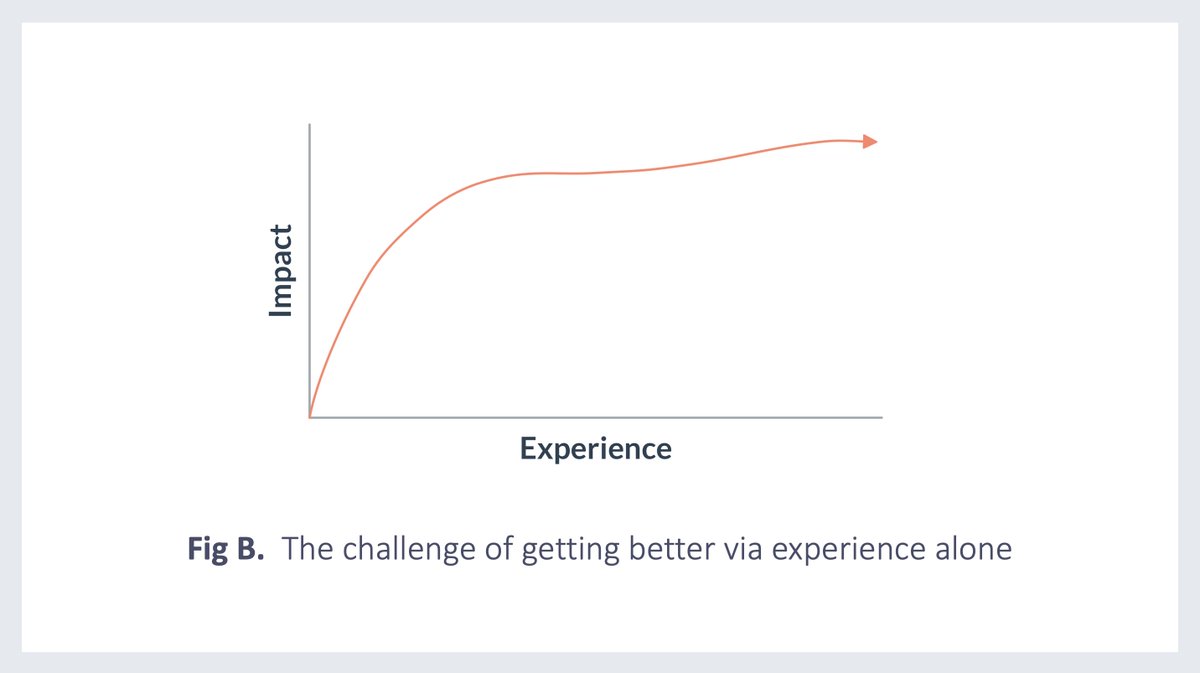

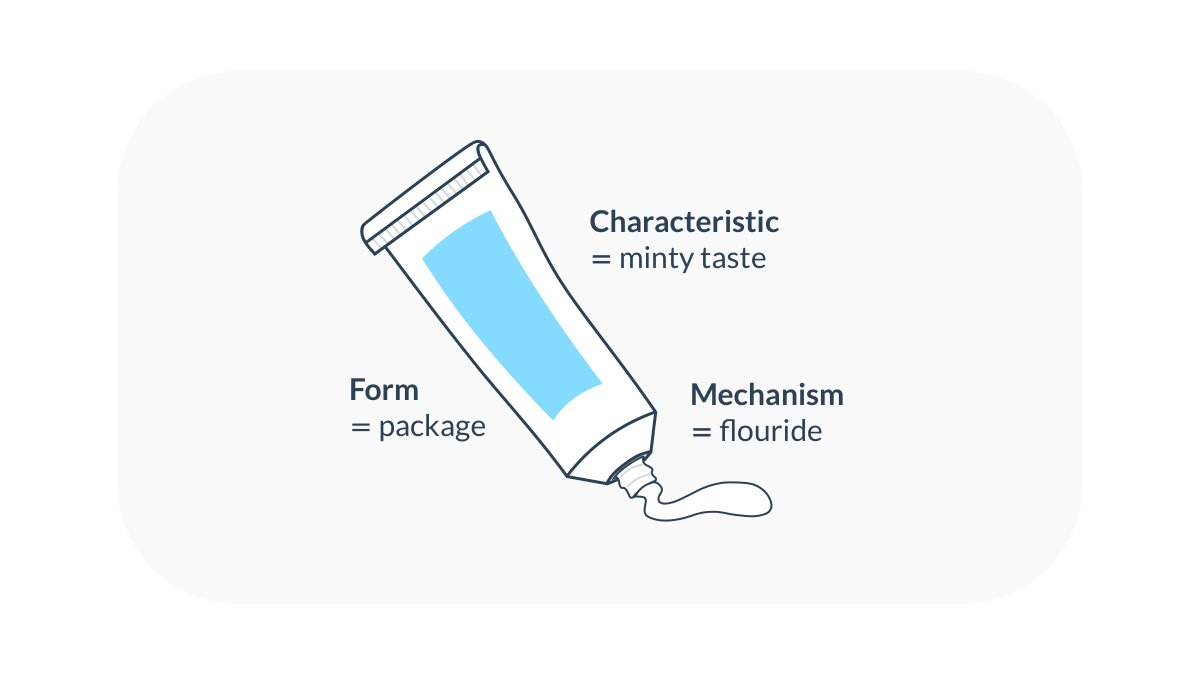

First, a reminder of why having a mental model of learning is useful for teachers. It can help us:

→ Better understand how our teaching strategies 'work'

→ Deploy them at the right time and in the right way

→ Adapt them for novel situations (and avoid lethal mutations)

→ Better understand how our teaching strategies 'work'

→ Deploy them at the right time and in the right way

→ Adapt them for novel situations (and avoid lethal mutations)

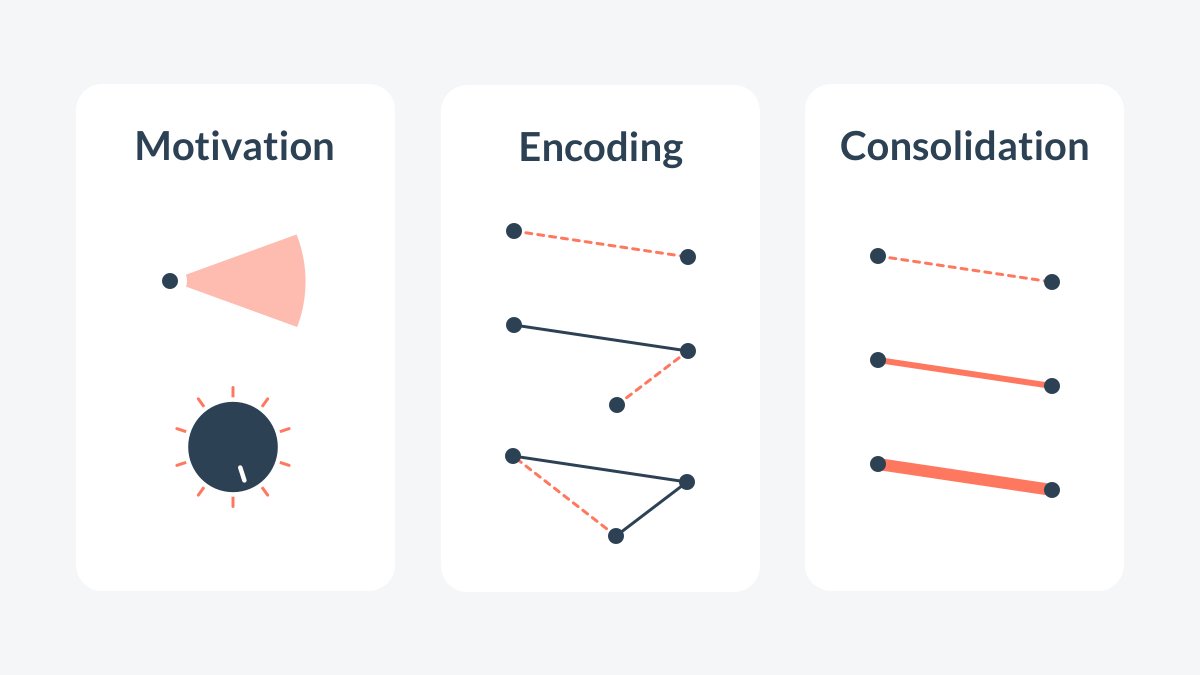

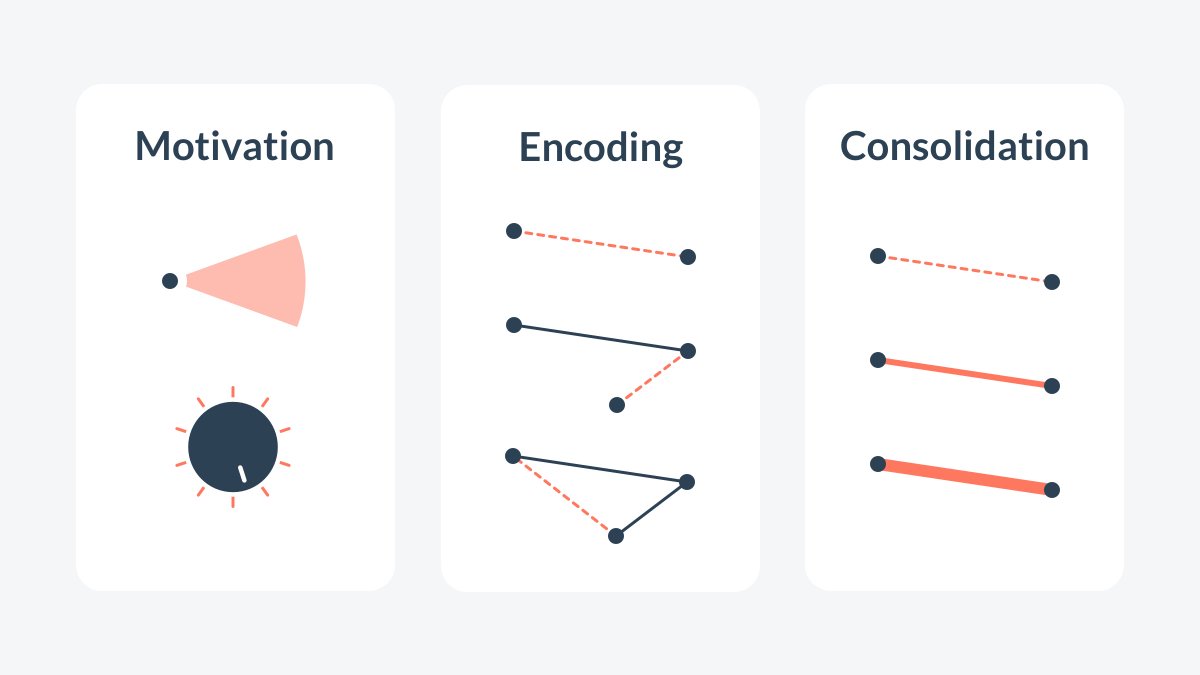

For me, at an individual level, learning involves 3 main processes:

1. Motivation

2. Encoding

3. Consolidation

The common linkage between these is attention.

1. Motivation

2. Encoding

3. Consolidation

The common linkage between these is attention.

Motivation is about influencing attention, both:

→ Direction: what to focus on

→ Magnitude: how strong that focus is (aka 'effort' or 'resilience')

→ Direction: what to focus on

→ Magnitude: how strong that focus is (aka 'effort' or 'resilience')

Encoding is about forging new connections to:

→ Generate fresh insights

→ Refine existing understanding

→ Generate fresh insights

→ Refine existing understanding

The relationship between motivation and encoding/consolidation is bi-directional:

👇 Motivation generates 'attentional potential'

☝️ Understanding and fluency build motivation

👇 Motivation generates 'attentional potential'

☝️ Understanding and fluency build motivation

As teachers, it's our job to routinely marshal these processes.

However, sometimes these processes require different teaching strategies, and so it's also important for us to manage the tensions and trade-offs between them.

However, sometimes these processes require different teaching strategies, and so it's also important for us to manage the tensions and trade-offs between them.

For example, introducing new insights whilst trying to build fluency can hamper consolidation (Davis et al., 2017*).

*core.ac.uk/download/pdf/2…

ht @adamboxer1

*core.ac.uk/download/pdf/2…

ht @adamboxer1

Either way, it can be useful to get into the habit of asking yourself:

→ What learning process am I trying to catalyse here?

→ What impact might it have on the other processes?

→ What learning process am I trying to catalyse here?

→ What impact might it have on the other processes?

Caveat: this is my mental model for learning at an *individual* level. It doesn't reflect social and cultural influences on learning.

And of course, it's still a work-in-progress. If you have suggestions for how it could be better, I'd love to hear them.

👊

And of course, it's still a work-in-progress. If you have suggestions for how it could be better, I'd love to hear them.

👊

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh