Sūrat Maryam (Q19) is well-known among scholars of the Quran for having a highly conspicuous passage (quran.com/19/34-40) which must be an interpolation.

The question however is: when was this section interpolated into the Quran? Manuscript evidence can give us some hints.🧵

The question however is: when was this section interpolated into the Quran? Manuscript evidence can give us some hints.🧵

Many scholars as early as Nöldeke and as recent as Guillaume Dye have pointed to these verses as looking like a conspicuous interpolation. And indeed the section really stands out for several reasons:

1. The rhyme scheme of Maryam is:

1-33: -iyyā

34-40: -UM (ūn/īm/īn)

35-74: -iyyā

75-98: -dā

In other words our passage abruptly disrupts the consistent (and unique to this Sūrah) rhyme -iyyā.

This is atypical for the Quran and makes the section stand out.

1-33: -iyyā

34-40: -UM (ūn/īm/īn)

35-74: -iyyā

75-98: -dā

In other words our passage abruptly disrupts the consistent (and unique to this Sūrah) rhyme -iyyā.

This is atypical for the Quran and makes the section stand out.

2. Narratively the Sūrah is perfectly coherent, with a clear narrative structure, when you remove this conspicuous section.

3. The suspected interpolation stands on its own and has a clear anti-Christian polemical tone, somewhat out of whack with the rest of the Sūrah.

3. The suspected interpolation stands on its own and has a clear anti-Christian polemical tone, somewhat out of whack with the rest of the Sūrah.

These are all compelling arguments for an interpolation. But it begs the question: when was this interpolation introduced? One might imagine that such an interpolation would be useful introduce in post-prophetic times when Islam more clearly distinguishes it from Christianity.

In recent years it has become clear that the standard text as we know it was certainly canonized no later than Uthman's reign (ca. 650 CE). And this passage is well-attested in early Uthmanic texts to confirm it was there in that recension.

corpuscoranicum.de/handschriften/…

corpuscoranicum.de/handschriften/…

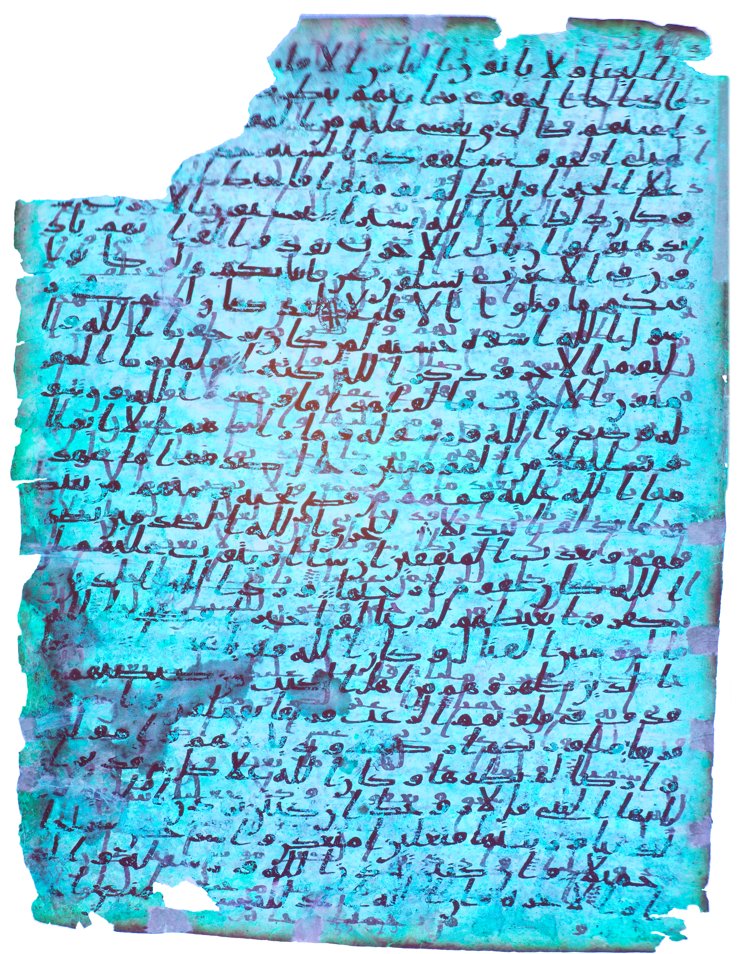

But as it turns out, the passage is even present in the Sanaa Palimpsest, an extremely early non-Uthmanic text, which Behnam Sadeghi has argued was a (copy of) one of the codices of the companions of the prophet.

This text is either a sister copy of the Uthmanic text, from an ultimate original archetype P (which Sadeghi identifies as a prophetic exemplar), or one of the companion copies that fed into the creation of the Uthmanic text.

In the edition of Sadeghi and @MohsenGT the relevant passage is attested. It deviates in some ways from the standard text, I've adapted their fastidious transcription somewhat and laid it out verse by verse and added all the dots. Green marks deviations from the Uthmanic text.

Q19:34 is identical except that after allaḏī the verb kāna 'it was' follows, with an unreadable gap which should leave room for an-nāsu, a reading reported for the codex of ʾUbayy b. Kaʿb: "That is Jesus, son of Mary - the word of truth about which the people used to dispute"

Q19:35 the wording is a little different. Rather than "It is not befitting for Allah to take any son", the text rather reads "Allah can not take a son".

The other variants are small to the point of being barely translatable. But clearly the interpolation is there.

The other variants are small to the point of being barely translatable. But clearly the interpolation is there.

So this tells us that the interpolation must even predate the Uthmanic recension project by some time, back to a time that variant companion codices were still around and held some authority already.

The manuscript record does retain a non-interpolated version.

The manuscript record does retain a non-interpolated version.

The fact that companion codex reports in the literary tradition likewise have variants reported (one of which also shows up in the Ṣanʿāʾpalimpsest), suggests that it wasn't just the Ṣanʿāʾ palimpsest that had this interpolation, other codices of the time did too.

This makes it it clear that the common ancestor of all these companion codices, that is the "prophetic archetype" already had these interpolations. That makes it quite likely that the prophet himself interpolated these verse at some point during his career.

There are other ways to explain the same data, but it would require quite radical rethinking of who was composing these portions of the Quran in the "prophetic" archetype, and it is difficult to see how the interpolation came to be widely accepted without an authoritative figure.

Of course the Islamic tradition reports at times examples of 'autointerpolation' by the prophet, where certain later revelations were inserted into certain sections of the Quran. This could very well be an example of that.

This is not the only case where the Ṣanʿāʾ palimpsest allows us to confirm the very ancient origins of interpolations. In fact, not a single verse present in the ʿUṯmānic text is missing in the Ṣanʿāʾ palimpsest (and vice versa!)!

In a short article I'm currently writing about the contents of the Ṣanʿāʾ palimpsest I make the point that in order to properly historically contextualize possible cases of interpolation, we have acknowledge the striking fact that they were already in place before canonization!

If you enjoyed this thread and want me to do more of it, please consider buying me a coffee.

ko-fi.com/phdnix.

If you want to support me in a more integral way, you can become a patron on Patreon!

patreon.com/PhDniX

ko-fi.com/phdnix.

If you want to support me in a more integral way, you can become a patron on Patreon!

patreon.com/PhDniX

INTERPOLATE *not between "does" and "retain" please. Sorry. Clumsiest typo ever.

ADDENDUM: I forgot a "not" in a rather crucial part of my thread 😂

https://twitter.com/PhDniX/status/1454182174278799373

ADDENDUM 2:

Interpolation: an insertion of a piece of text after its original composition.

Autointerpolation: an insertion of a piece of text after its original composition, by the person who composed the original composition.

Interpolation: an insertion of a piece of text after its original composition.

Autointerpolation: an insertion of a piece of text after its original composition, by the person who composed the original composition.

https://twitter.com/still_reading/status/1454181985166020619

ADDENDUM 3:

*sigh* I'm definitely not on my A game tonight.

*sigh* I'm definitely not on my A game tonight.

https://twitter.com/PhDniX/status/1454187712945262598

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh