This inspired me to make a small🧵about this phenomenon from one of my own fields of study, the niche field of pre-Islamic South Arabian studies.

About South Arabia's identification with India (what?!) and sourcing on Wikipedia. Let's have a look.

About South Arabia's identification with India (what?!) and sourcing on Wikipedia. Let's have a look.

https://twitter.com/5katkov/status/1455141952463192064

This is from the Wikipedia page "South Arabia". Overall, it's not bad. At times, it feels a bit amateuristic, but I've seen worse.

But look at the etymology part. Yes, sometimes South Arabia is identified with India in Greek and Roman (and also Jewish Aramaic) texts, but why?

But look at the etymology part. Yes, sometimes South Arabia is identified with India in Greek and Roman (and also Jewish Aramaic) texts, but why?

Wikipedia says that's because the Persians, who annexed the area around 560, thought Indians and Ethiopians were similar, as both are "dark-skinned". This makes alarm bells go off, because references to South Arabia-as-India are much older than that. But let's look at the source.

The source Wikipedia gives is Richard Bell's 1926 "The Origin of Islam in its Christian Environment". That's 80 years old at this point. So where did Bell come up with this idea?

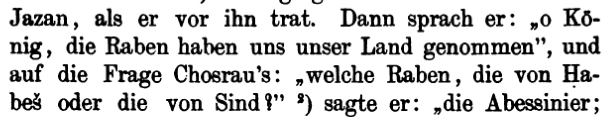

We're going farther down the rabbit hole, to Nöldeke's Geschichte der Araber und Perser, from 1879.

We're going farther down the rabbit hole, to Nöldeke's Geschichte der Araber und Perser, from 1879.

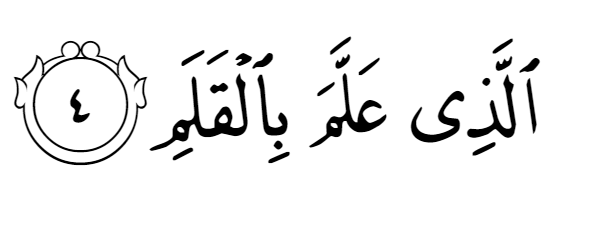

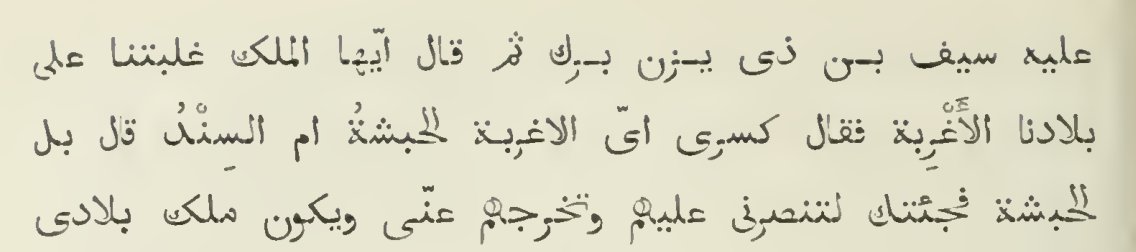

At this point, we're in the later half of the 19th century. This text is basically a translation of the South Arabia narrative found in al-Tabarī's History of Kings and Prophets:

"The ravens have come to us". The Persian king replies "which ones, the Ethiopians or Indians?"

"The ravens have come to us". The Persian king replies "which ones, the Ethiopians or Indians?"

In short, Wikipedia's statement on South Arabia's identification with India is based on a 1926 book, which cites a 1879 translation of a 10th century Islamic legend.

As far as I'm aware, there are no contemporaneous Persian sources identifying South Arabia with India.

As far as I'm aware, there are no contemporaneous Persian sources identifying South Arabia with India.

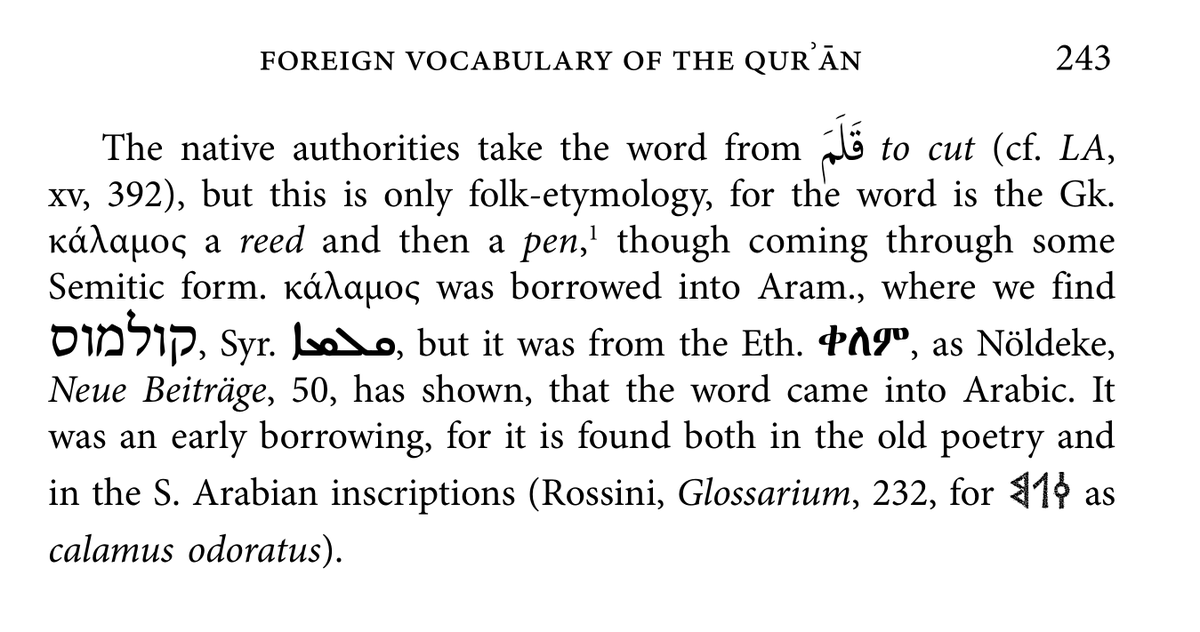

Where do we find identifications of South Arabia with India? Pieter van der Horst, professor emeritus of Utrecht University, wrote a great article entitled '"India" in Early Jewish Literature".

References exist in Greek, Latin, Hebrew, Aramaic, and Coptic.

References exist in Greek, Latin, Hebrew, Aramaic, and Coptic.

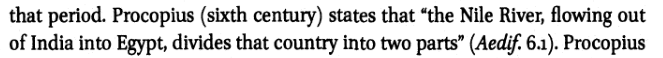

In reality, as time progressed, Greek and Roman writers began to think India and Africa were somehow connected. It's not entirely clear why, but it's probably because of an imperfect understanding of geography.

For this reason we also find people named "the Indian" connected with South Arabia or East Africa. What we find in al-Tabarī and Nöldeke is not the *cause* of this popular identification of India and South Arabia/East Africa, but a result.

Anyway, there is so much more to be said about this, and I do have a class to prepare. Anyway, don't trust everything you read on Wikipedia, kids!

~ fin ~

~ fin ~

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh