Was there anyone who could read South Arabian inscriptions after the coming of Islam?

A thread 🧵re-evaluating the skills of the Yemeni scholar al-Hamdānī (died c. 950), and what he knew about the inscriptions of pre-Islamic South Arabia.

A thread 🧵re-evaluating the skills of the Yemeni scholar al-Hamdānī (died c. 950), and what he knew about the inscriptions of pre-Islamic South Arabia.

Al-Hamdānī was so well-known for his knowledge on anything related to South Arabia that he earned the nickname Lisān al-Yaman, i.e. "The tongue of Yemen". This is no joke: he knew things about astronomy, geography, history, topography, linguistics, folklore, metallurgy, and more.

As far as we know, he authored three books:

- Ṣifat ǧazīrat al-ʿarab, "Description of the Arabian Peninsula"

- Kitāb al-ǧawharatayn, "The book of the two metals [i.e. gold & silver")

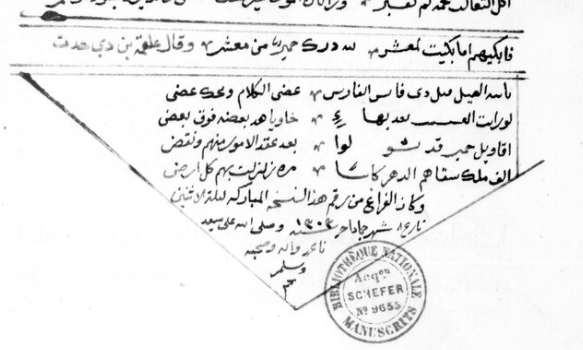

- Kitāb al-Iklīl, "The Crowns".

Of this last one, only volumes 1, 2, 8, 10 & 12 survived.

- Ṣifat ǧazīrat al-ʿarab, "Description of the Arabian Peninsula"

- Kitāb al-ǧawharatayn, "The book of the two metals [i.e. gold & silver")

- Kitāb al-Iklīl, "The Crowns".

Of this last one, only volumes 1, 2, 8, 10 & 12 survived.

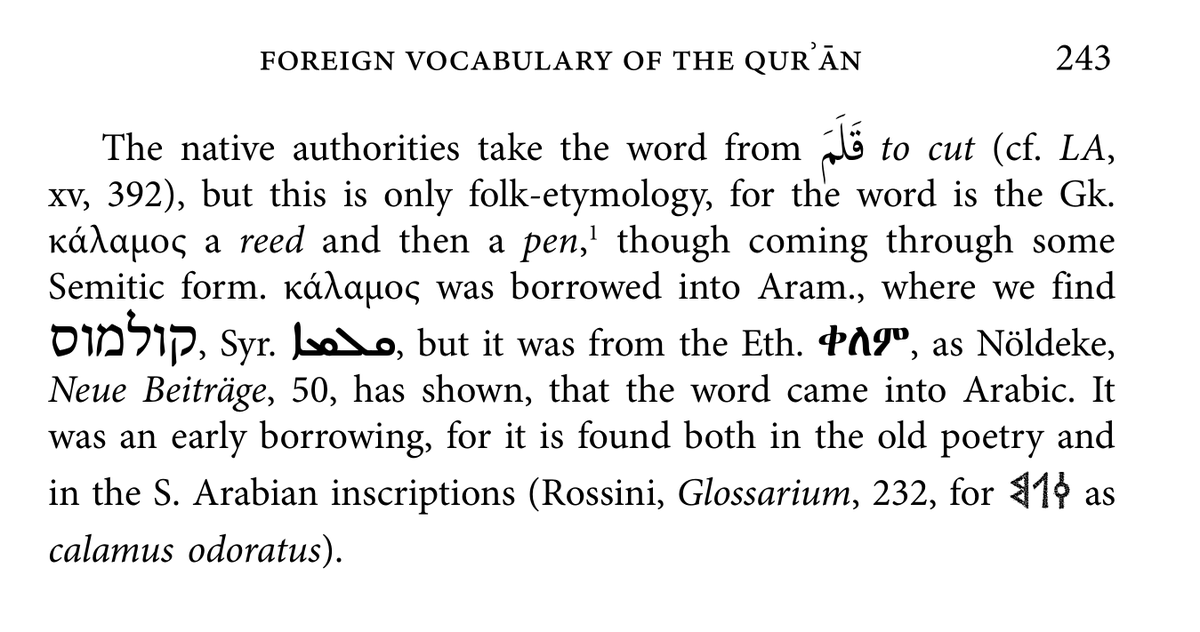

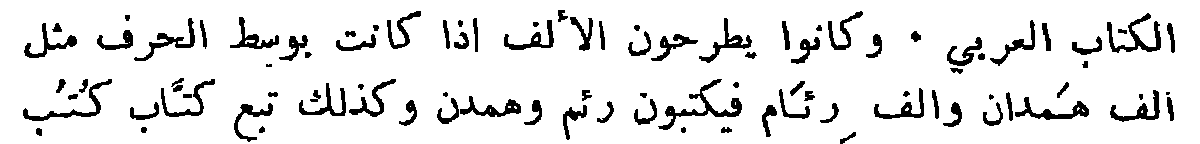

Let's look at al-Iklīl, vol. VIII. This is one of my favorite books, as it contains a lot of spooky South Arabian folklore (for another time). It also contains a short chapter on what he calls "the letters of the musnad". He is referring to South Arabian script, of course.

Al-Hamdānī knew:

1. That one letter could have several shapes

2. That ʾlif was not used to write long vowels

3. That the masculine 3rd person pl suffix was written <hmw>

4. About word-dividers

5. How to read and transcribe the inscriptions.

Let's take a closer look:

1. That one letter could have several shapes

2. That ʾlif was not used to write long vowels

3. That the masculine 3rd person pl suffix was written <hmw>

4. About word-dividers

5. How to read and transcribe the inscriptions.

Let's take a closer look:

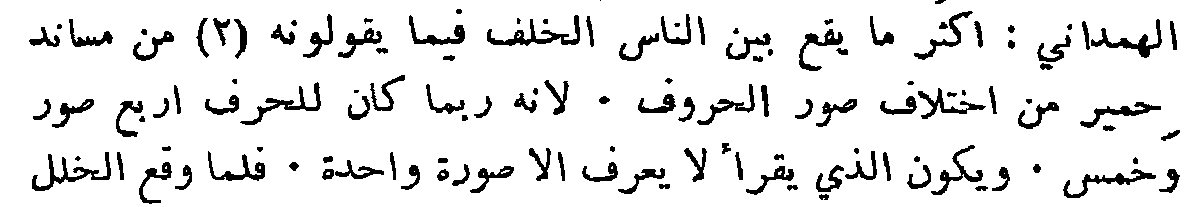

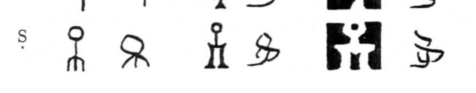

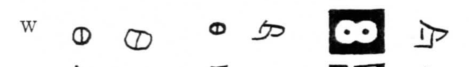

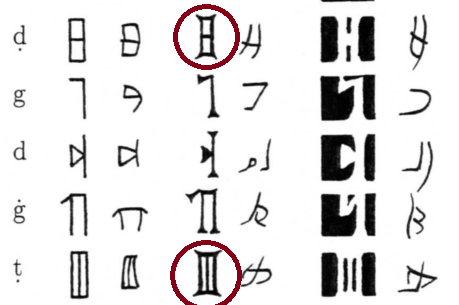

1. "Most of the disagreements regarding the inscriptions of Himyar stem from the letters' different shapes. So, someone who would read them might only know just one shape".

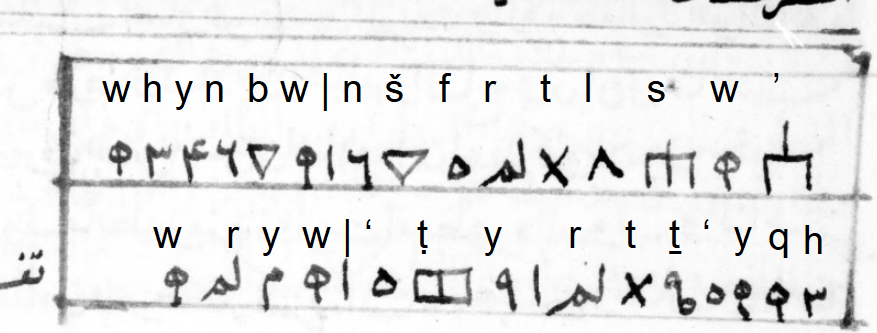

And when we look at the South Arabian scripts, some letters did indeed evolve differently, e.g., <ṣ>, <w>

And when we look at the South Arabian scripts, some letters did indeed evolve differently, e.g., <ṣ>, <w>

2. “They elided the ʾalif, if it occurred in the middle of the letter, such as in Hamdān and Riyyām, which they wrote as Hamdan and Riyyam."

In Sabaic, matres lectiones were not used word-internally. Why al-Hamdānī talks about just alif, and not waw and yā, is unclear, though.

In Sabaic, matres lectiones were not used word-internally. Why al-Hamdānī talks about just alif, and not waw and yā, is unclear, though.

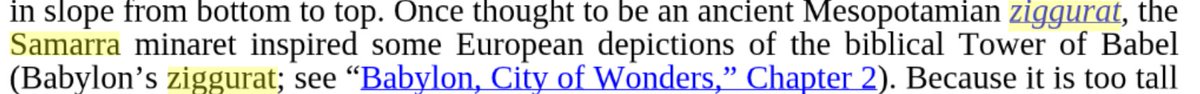

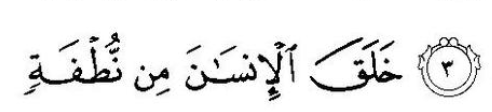

Al-Hamdānī compares this to the Qur'ānic spellings <rḥmn>, i.e. Raḥmān; and <ʾnsn>, i.e. insān. Even today, it is not uncommon to find al-Raḥmān spelled without an alif, but the defective spelling of insān is quite typically Qur'ānic!

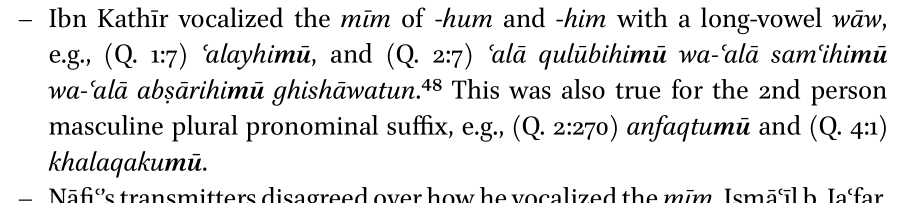

3. "They would also add a ḍamma at the end of a word, as well as a waw; i.e., alayhimū."

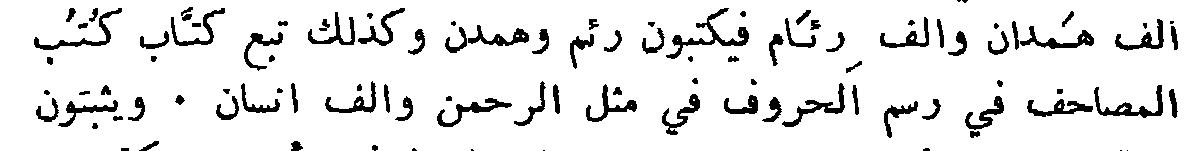

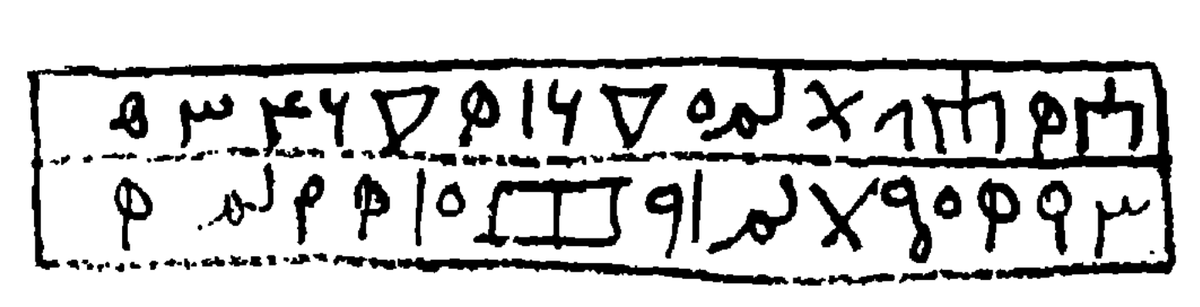

The Sabaic 3rd person masculine pronominal suffix was written <hmw>, as in this inscription (BR-M. Bayḥān 4). The 1st word of the 2nd line reads <w-bny-hmw>, i.e. "and their sons".

The Sabaic 3rd person masculine pronominal suffix was written <hmw>, as in this inscription (BR-M. Bayḥān 4). The 1st word of the 2nd line reads <w-bny-hmw>, i.e. "and their sons".

Al-Hamdānī compares that to the "recitation of the folk of Mecca, and those resembling them; except that it was required to be written".

The Meccan reciter Ibn Kathīr al-Makkī (d. 738) does recite ʿalay-humū & ʿalay-himū. A very astute observation.

The Meccan reciter Ibn Kathīr al-Makkī (d. 738) does recite ʿalay-humū & ʿalay-himū. A very astute observation.

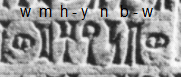

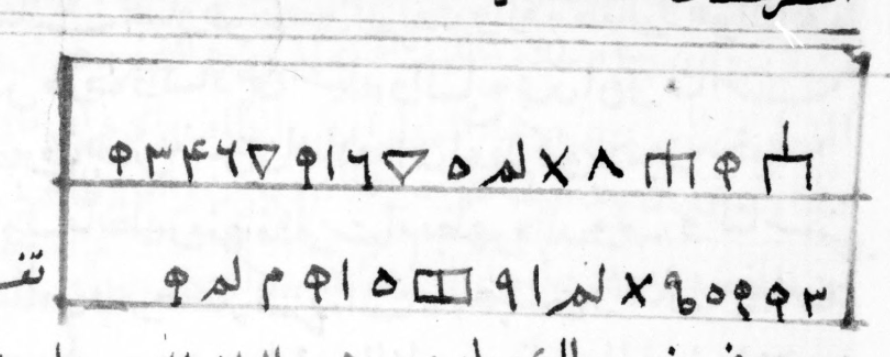

“They would separate two lines with a single stroke, and separate words with a vertical line."

Hamdānī is referring to what we would call word dividers. These were used to indicate, er, divisions between words. And yes, these were just a simple vertical stroke, such as here:

Hamdānī is referring to what we would call word dividers. These were used to indicate, er, divisions between words. And yes, these were just a simple vertical stroke, such as here:

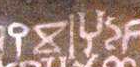

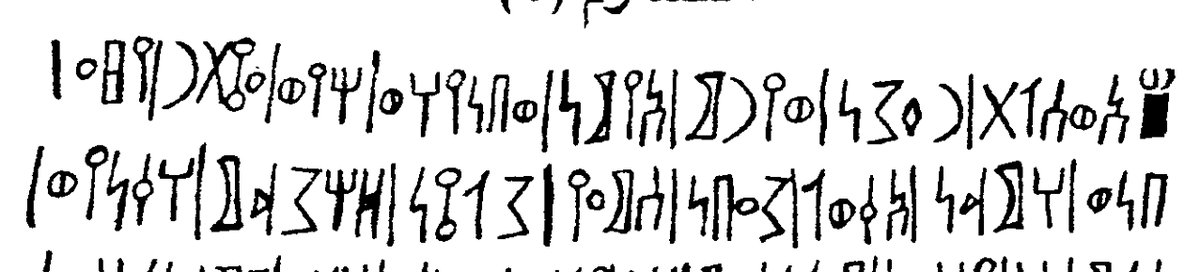

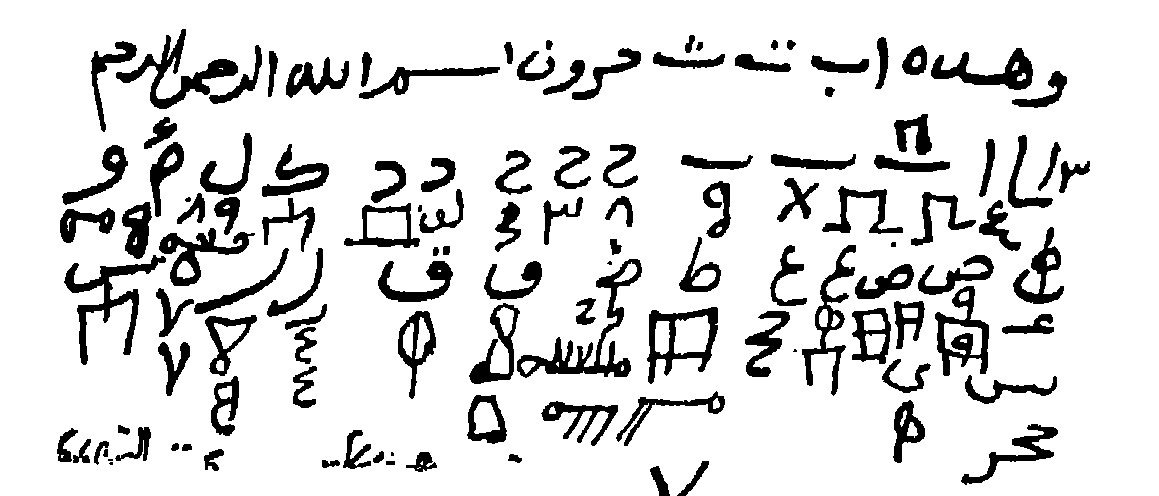

5.. Finally, al-Hamdānī shows us an actual inscription and its transcription in Arabic, too. It is a bit difficult to make out, recognizable, especially when you know the South Arabian script.

He reads this as: ʾAwsala Rafšān wa-banī-hū haqniya ʕaṯtar yāṭiʿ wa-yarīm.

He reads this as: ʾAwsala Rafšān wa-banī-hū haqniya ʕaṯtar yāṭiʿ wa-yarīm.

Is this a real South Arabian inscription?

It would seem so! The phrasing is very, very close to that of inscription Ir 4 (pre-4th century), which starts like this:

ʾwslt Rfšn w-ʾymn w-bny-hw Ḥywʿṯtr Yḍʕ bnw Hmdn ʔqwl šbʕn bn Smʕy šlṯn d-Ḥšdm hqnyw ʔlmqh Tḥwn...

It would seem so! The phrasing is very, very close to that of inscription Ir 4 (pre-4th century), which starts like this:

ʾwslt Rfšn w-ʾymn w-bny-hw Ḥywʿṯtr Yḍʕ bnw Hmdn ʔqwl šbʕn bn Smʕy šlṯn d-Ḥšdm hqnyw ʔlmqh Tḥwn...

Hamdānī gets most of it right, but there are some mistakes

1. He forgot to write the <n> in <hqny> "he dedicated", but gets it right in transcription.

2. He probably mixed up the <ṭ> and <ḍ>; they're quite similar.

3. He mixed up (or misrembered) ʿAṯtar and ʾIlmuquh.

1. He forgot to write the <n> in <hqny> "he dedicated", but gets it right in transcription.

2. He probably mixed up the <ṭ> and <ḍ>; they're quite similar.

3. He mixed up (or misrembered) ʿAṯtar and ʾIlmuquh.

Most of these mistakes can be forgiven, especially considering that Hamdānī probably did not copy this immediately.

Does this mean that al-Hamdānī understood the writing's meaning, though? Vol. 7 of al-Iklīl, which supposedly goes into more detail on this inscriptions, is lost.

Does this mean that al-Hamdānī understood the writing's meaning, though? Vol. 7 of al-Iklīl, which supposedly goes into more detail on this inscriptions, is lost.

But that he does not go beyond transcription, probably shows he knew the letters, but not what what the inscriptions meant.

And let's keep in mind, he was reading inscriptions already over half a millennium old! An incredible feat, whatever way you look at it.

And that's it.

And let's keep in mind, he was reading inscriptions already over half a millennium old! An incredible feat, whatever way you look at it.

And that's it.

Thank you, @PhDniX for the observation regarding Ibn Kathīr al-Makkī's recitations. You're the real MvP.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh