Every day clinicians struggle with equipment, space and layout that encumbers, rather than helps them do their job.

A 🧵on how we applied human factors principles, usability testing & #simulation informed design to our new pediatric resus tower

1/

A 🧵on how we applied human factors principles, usability testing & #simulation informed design to our new pediatric resus tower

1/

Our previous cart was a Broselow (color) based design. Lots of good human factors principles here but it's clear that even good HF intentions can be overcome when cluttered. Also the equip wasn't optimal.

Following design thinking principles, we began defining the problem

2/

Following design thinking principles, we began defining the problem

2/

We did substantial listening to our staff and seeking out expert feedback from pediatric MD & RN colleagues who work at peds centres.

We reviewed clinical cases.

We ran peds simulations with our existing equipment & identified several issues.

2/

We reviewed clinical cases.

We ran peds simulations with our existing equipment & identified several issues.

2/

What we learned that while the colors directed the staff to the appropriate drawers, it didn't help them complete key tasks. Issues included

- monitoring/vitals

- IV placement equip was missing

- difficulty finding equip in each drawer

- variable airway equipment

3/

- monitoring/vitals

- IV placement equip was missing

- difficulty finding equip in each drawer

- variable airway equipment

3/

So we started prototyping.

This is key in the #design process. Its not sufficient to write this down and then just order something from a catalogue.

We did start with a paper concept but then we built something tangible. Prototyping is underappreciated in healthcare.

4/

This is key in the #design process. Its not sufficient to write this down and then just order something from a catalogue.

We did start with a paper concept but then we built something tangible. Prototyping is underappreciated in healthcare.

4/

We also reviewed the literature and I reached out to people on twitter for feedback.

In fact, we built our NRP drawer from a concept that has been described whereby each NRP step is a separate bundle...a decision we figured we'd trial but abandon if didn't work for us

5/

In fact, we built our NRP drawer from a concept that has been described whereby each NRP step is a separate bundle...a decision we figured we'd trial but abandon if didn't work for us

5/

A few of our key design principles:

1. Remove friction for end-users to complete their task

2. Labelling needed to be clear and clinician-focused (not stocking focused)

3. We followed a similar well established cart design by @HumanFact0rz, leveraging familiarity

6/

1. Remove friction for end-users to complete their task

2. Labelling needed to be clear and clinician-focused (not stocking focused)

3. We followed a similar well established cart design by @HumanFact0rz, leveraging familiarity

6/

4. Bundling equipment for frequent/predictable tasks

5. Task specific levels/drawers

6. Maintaining broselow colouring for equipment

We then iteratively refined our prototypes.

7/

5. Task specific levels/drawers

6. Maintaining broselow colouring for equipment

We then iteratively refined our prototypes.

7/

It's key to remind the users that the process is dynamic. That the "end" state won't be achieved immediately.

Too quickly in healthcare we jump to "implementation" of final products...that simply don't work.

8/

Too quickly in healthcare we jump to "implementation" of final products...that simply don't work.

8/

We conducted usability testing to better understand how people worked. We compared our previous cart with the new one

RNs/MDs/clinical assistants

We ran task-based simulations at first, monitoring time to task completion, qualitative user feedback and soliciting new ideas

9/

RNs/MDs/clinical assistants

We ran task-based simulations at first, monitoring time to task completion, qualitative user feedback and soliciting new ideas

9/

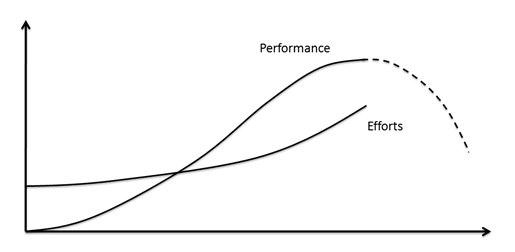

The data helped confirm our assumptions. We didn't make these decisions around a boardroom, divorced from the clinical space.

Rather the process put the user at the center, increasing our confidence that the end product would yield dividends for clinical performance

10/

Rather the process put the user at the center, increasing our confidence that the end product would yield dividends for clinical performance

10/

We also engaged multiple users in the process, seeking their feedback.

People want to be involved in making their workplace better. This builds a culture of performance and safety.

11/

People want to be involved in making their workplace better. This builds a culture of performance and safety.

11/

Interestingly people asked about making our labelling colorful like we've done with our previous resus towers, but we found this confused users when Broselow was used.

So we maintained easy to read, high contrast monochromatic labels.

This is our current prototype.

12/

So we maintained easy to read, high contrast monochromatic labels.

This is our current prototype.

12/

We brought it out for a pilot simulation a few wks ago.

Again there was some great feedback and we're conducting final tweaks while we wait for the custom built tower to arrive from the manufacturer.

Again there was some great feedback and we're conducting final tweaks while we wait for the custom built tower to arrive from the manufacturer.

This process relied heavily on #simulation informed design, usability testing and human factors principles.

We're not done yet...but we've learned alot

1. end-user feedback is critical

2. build prototypes

3. test & revise using simulation

4. integrate HF elements

END

We're not done yet...but we've learned alot

1. end-user feedback is critical

2. build prototypes

3. test & revise using simulation

4. integrate HF elements

END

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh