Want to publish in top journals?

Check the first sentence of your ABSTRACT and INTRO.

Does it introduce:

A: Your project?

OR

B: Your Field?

Learn why it MUST be B and how to diagnose and fix it in your own papers.

#phdchat

Check the first sentence of your ABSTRACT and INTRO.

Does it introduce:

A: Your project?

OR

B: Your Field?

Learn why it MUST be B and how to diagnose and fix it in your own papers.

#phdchat

2/ Thread structure:

- Places to relate to your reader

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Diagnose your own paper

- What NOT TO DO – negative examples

- More detailed material

Let’s dive in ⬇️

- Places to relate to your reader

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Diagnose your own paper

- What NOT TO DO – negative examples

- More detailed material

Let’s dive in ⬇️

3/ There are different places we can relate to our reader:

Abstract

Introduction

Conclusion

Let’s start with the abstract.

Abstract

Introduction

Conclusion

Let’s start with the abstract.

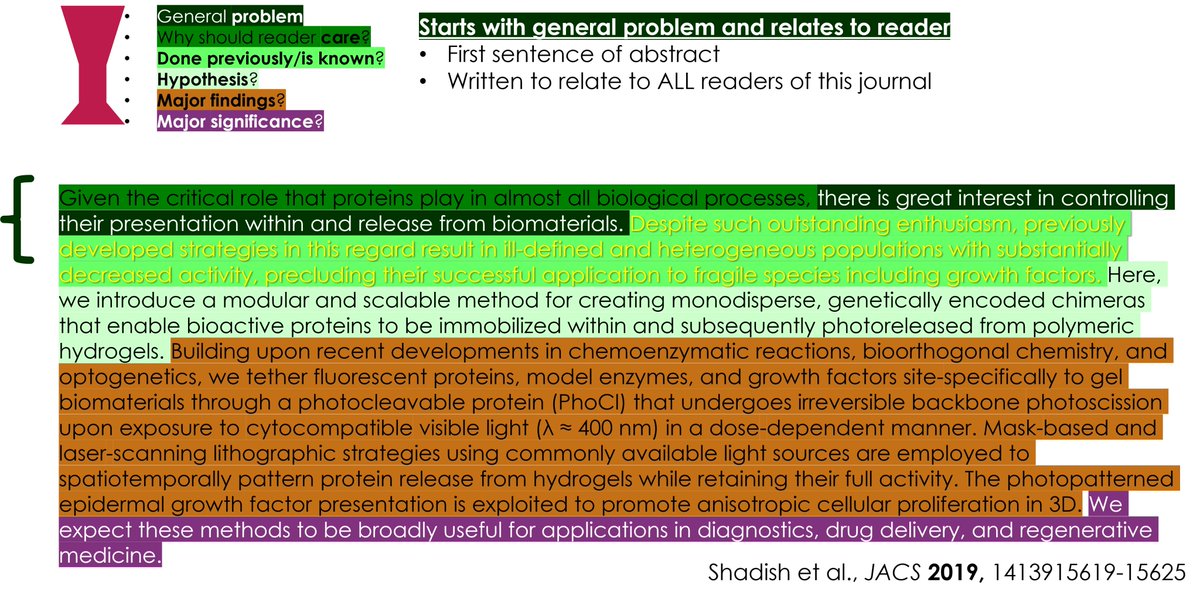

4/Abstract

This ideal abstract shows that the VERY FIRST SENTENCE here starts with a problem general enough for the average reader to relate and tells them

WHY

they should care.

Perfect

The reader knows how to place your work in context aka how to tell if your work is important

This ideal abstract shows that the VERY FIRST SENTENCE here starts with a problem general enough for the average reader to relate and tells them

WHY

they should care.

Perfect

The reader knows how to place your work in context aka how to tell if your work is important

5/ Same goes for your introduction

It starts with a broad scope, though here is a full paragraph

It conveys a major problem a reader can relate to

Overall, this paragraph explains why your FIELD of research is important and tells a reader why they should care about your project

It starts with a broad scope, though here is a full paragraph

It conveys a major problem a reader can relate to

Overall, this paragraph explains why your FIELD of research is important and tells a reader why they should care about your project

6/ Remember in your intro:

End this first paragraph on a GAP statement!

This GAP should be the reason your FIELD of research exists – why is work in this field necessary?

End this first paragraph on a GAP statement!

This GAP should be the reason your FIELD of research exists – why is work in this field necessary?

7/ Diagnose it:

Relating to the reader ABSTRACT + INTRO

Notice how the flow changes when the relatable part is buried after a definition.

If you don’t have a solid reason for reading this paper

And

It’s not your field,

you probably don’t get much further than the first sentence.

Relating to the reader ABSTRACT + INTRO

Notice how the flow changes when the relatable part is buried after a definition.

If you don’t have a solid reason for reading this paper

And

It’s not your field,

you probably don’t get much further than the first sentence.

8/ This is the MOST COMMON MISTAKE here.

Without relating broadly to the reader, this paper will seem irrelevant for anyone who isn’t directly in the field and already knows the importance.

➡️ Definitions are isolating.

Start broad, include the definition later.

Without relating broadly to the reader, this paper will seem irrelevant for anyone who isn’t directly in the field and already knows the importance.

➡️ Definitions are isolating.

Start broad, include the definition later.

9/ Another negative example:

The problem starts similarly to above: Not relating to the reader.

This abstract skips any relation at all.

Again: FOCUS on having a broad statement at the beginning that places this work into context for your reader.

The problem starts similarly to above: Not relating to the reader.

This abstract skips any relation at all.

Again: FOCUS on having a broad statement at the beginning that places this work into context for your reader.

10/ FIX IT: Brainstorm

→ Incessantly ask yourself WHY (i.e., pretend you are a small kid)

1. Ask yourself WHY until you get to your BIGGER PICTURE

2. Brainstorm the answers to forward-thinking questions

→ Incessantly ask yourself WHY (i.e., pretend you are a small kid)

1. Ask yourself WHY until you get to your BIGGER PICTURE

2. Brainstorm the answers to forward-thinking questions

11/ Brainstorm the answers to these forward-thinking questions:

- What specially does your research do to advance science?

- What exactly does this bring to the field? How has it advanced the field?

- What can be build/done/made/calculated now that your research exists?

- What specially does your research do to advance science?

- What exactly does this bring to the field? How has it advanced the field?

- What can be build/done/made/calculated now that your research exists?

12/ Give the reader something they can relate to while reading.

🧨Your work only matters as much as you can convince others that it does.

If you can’t convince someone your research is worth publishing or funding, your idea is literally worthless.

Let’s not let that happen.

🧨Your work only matters as much as you can convince others that it does.

If you can’t convince someone your research is worth publishing or funding, your idea is literally worthless.

Let’s not let that happen.

6/ More detailed information:

Find more details material at my blog post: butlerscicomm.com/what-to-do-whe…

or

my new YouTube video about it:

Find more details material at my blog post: butlerscicomm.com/what-to-do-whe…

or

my new YouTube video about it:

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter