I’d like to talk about the finances - and potential financial conflict of interest - at the National Board of Medical Examiners.

This is gonna be a long one - but thanks for hearing me out.

(Thread)

This is gonna be a long one - but thanks for hearing me out.

(Thread)

Yesterday, I started a discussion about how our focus on #USMLE Step 1 was hurting both undergraduate and graduate medical education.

It’s gotten a lot of attention, probably because I highlighted a comment from the CEO of the NBME that touched a nerve for a lot of you.

It’s gotten a lot of attention, probably because I highlighted a comment from the CEO of the NBME that touched a nerve for a lot of you.

Beyond that quote, when I read the article, what struck me was this:

The CEOs of the NBME and FSMB expressed numerous concerns about adverse effects of making USMLE Step 1 pass/fail...

...but loss of revenue to the @NBMEnow was not mentioned.

The CEOs of the NBME and FSMB expressed numerous concerns about adverse effects of making USMLE Step 1 pass/fail...

...but loss of revenue to the @NBMEnow was not mentioned.

I’m going to share some data on the NBME’s finances, and let you draw your own conclusions about whether the evolution and current financial structure of the NBME might lead to #COI.

But let’s begin somewhere else. Why does the NBME exist in the first place?

But let’s begin somewhere else. Why does the NBME exist in the first place?

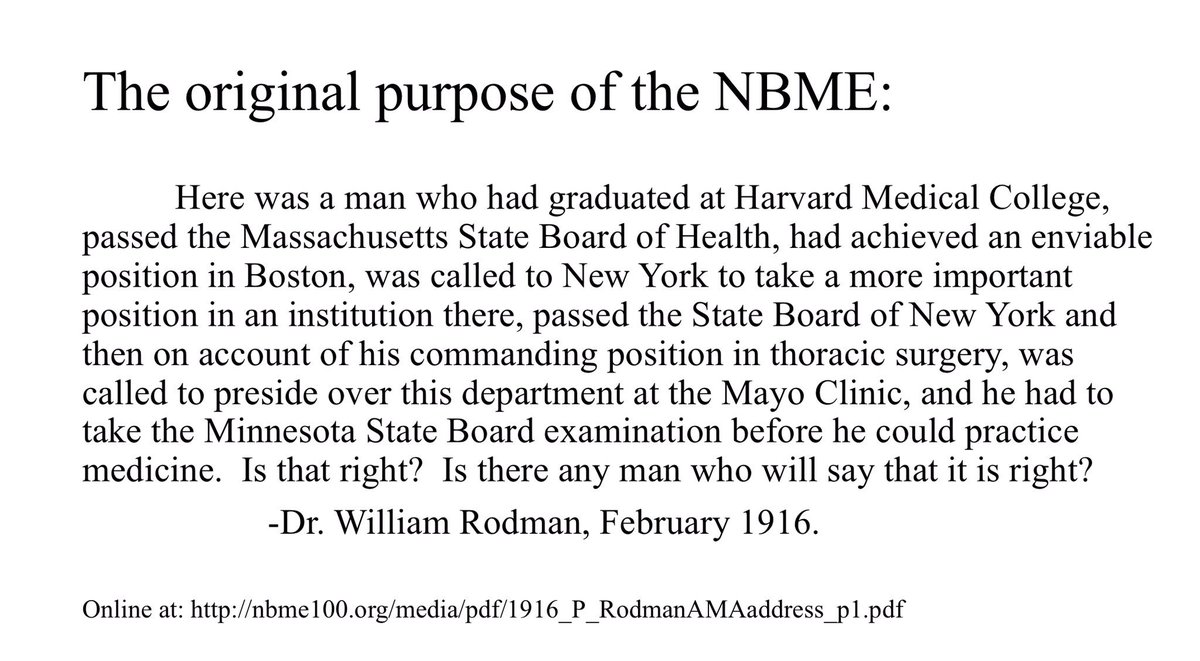

The NBME was founded in 1916 in large part to address an annoying problem for physicians. Since medical licensure is regulated at the state level, a physician had to take a separate board examination in each and every state in which he intended to practice.

So that’s pretty cool, right? Thanks to the NBME, all MDs can take the same test and then seek licensure wherever they want. (Compare that to attorneys, where taking a new state bar exam is a significant barrier to movement and may lead to workforce inefficiencies.)

In terms of accomplishing its primary mission, the NBME can say it’s done it for the past 100 years.

(Hold that thought.)

(Hold that thought.)

Now, let’s talk $.

The data shared here are all publicly available. As a 501(c)(3) organization, the NBME is reports its finances annually on an IRS Form 990.

Want to check my figures? The IRS forms are online at @ProPublica’s Nonprofit Explorer.

projects.propublica.org/nonprofits/

The data shared here are all publicly available. As a 501(c)(3) organization, the NBME is reports its finances annually on an IRS Form 990.

Want to check my figures? The IRS forms are online at @ProPublica’s Nonprofit Explorer.

projects.propublica.org/nonprofits/

Unlike many nonprofits, the NBME neither solicits nor accepts charitable donations.

They derive a small amount of income (~3%) from investments.

But the overwhelming majority of their $ comes from their programs (i.e., the USMLE, which accounts for ~75% of their revenue).

They derive a small amount of income (~3%) from investments.

But the overwhelming majority of their $ comes from their programs (i.e., the USMLE, which accounts for ~75% of their revenue).

Next thing to know is that the “pipeline” of USMLE test takers has been pretty stable.

Since 2007, the number of first-time test takers (including both US/Canadian and foreign medical school graduates) has been around 40-42,000/year.

Since 2007, the number of first-time test takers (including both US/Canadian and foreign medical school graduates) has been around 40-42,000/year.

So, given that:

a) the number of USMLE test takers is stable;

and

b) the NBME is a nonprofit corporation whose primary reason for existence was accomplished long ago;

...what trend would you expect to see in NBME program revenue from 2001 to 2017?

a) the number of USMLE test takers is stable;

and

b) the NBME is a nonprofit corporation whose primary reason for existence was accomplished long ago;

...what trend would you expect to see in NBME program revenue from 2001 to 2017?

Here is the @NBMEnow’s program service revenue, which has more than tripled, from $47.5 million in 2001 to $153.9 million in 2017.

For those of you wondering, this increase is NOT explained by inflation.

Using the Bureau of Labor Statistics consumer price index, $47.5 million dollars in 2001 would be equivalent to $65.6 million in 2017.

Using the Bureau of Labor Statistics consumer price index, $47.5 million dollars in 2001 would be equivalent to $65.6 million in 2017.

To put this in some perspective, consider this:

From the start of 2001 to the close of 2017, the Dow Jones Industrial Average increased from 10,646 to 24,719 - a factor of 2.3.

NBME program revenues increased by a factor of 3.24.

From the start of 2001 to the close of 2017, the Dow Jones Industrial Average increased from 10,646 to 24,719 - a factor of 2.3.

NBME program revenues increased by a factor of 3.24.

So what led to such a steep increase in revenue?

Two things: increased cost for the USMLE, and new revenue streams from new USMLE programs.

Two things: increased cost for the USMLE, and new revenue streams from new USMLE programs.

As far as the cost of USMLE over time: here’s where I need some help from #medtwitter. The data I can find are spotty, and I don’t have the cost for every year. If someone can help me, I will put together a chart.

As far as new revenue streams, the NBME has created several.

The increase in program revenue around 2004-2005 was from the introduction of a new test: the USMLE Step 2 Clinical Skills (CS) exam.

The increase in program revenue around 2004-2005 was from the introduction of a new test: the USMLE Step 2 Clinical Skills (CS) exam.

Step 2 CS is the most expensive product in the USMLE line - $1285 for U.S. students in 2018.

The cost to students is large - but because 96% of U.S. first-time test takers pass, the discriminatory value to licensing agencies is minimal.

ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23465102

The cost to students is large - but because 96% of U.S. first-time test takers pass, the discriminatory value to licensing agencies is minimal.

ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23465102

Much, much more about the (lack of) value of Step 2 CS has been discussed previously. If you missed it, I’ll leave it to the rest of the #meded community to fill you in.

In the background throughout the time period shown was the steadily-building crescendo of Step 1 mania that I discussed yesterday. The NBME is not primarily responsible for that - but they have undoubtedly benefitted financially by selling new products.

For example, in 2007, they began offering Customized Assessment Services (CAS), a program that allows medical schools to create examinations using “cold” NBME test items.

By 2017, 83 US medical schools were using CAS, and the number of exams administered had doubled since 2013.

By 2017, 83 US medical schools were using CAS, and the number of exams administered had doubled since 2013.

They also sold more “shelf exams” - the subject tests used at the end of clinical clerkships.

By the way, all of the medical students at my school pay for the shelf exams and CAS - the costs are just less transparent since the dollar amounts are rolled into the tuition bill.

By the way, all of the medical students at my school pay for the shelf exams and CAS - the costs are just less transparent since the dollar amounts are rolled into the tuition bill.

The NBME has also increased revenue from its Self Assessment Services. Here, students can purchase NBME question blocks at $60 apiece to help them prepare for the mandatory NBME tests later on.

And what does the NBME do with all of this revenue?

It’s time to discuss salaries.

It’s time to discuss salaries.

Top executives at the NBME are handsomely compensated.

Immediate past president Donald Melnick received total compensation of $1,265,066 in 2015.

Immediate past president Donald Melnick received total compensation of $1,265,066 in 2015.

Dr. Melnick’s compensation rose along the rising financial tides at the NBME, increasing from $399,160 in 2001 to over $1.2 million in 2015, almost perfectly in parallel with the tripling of program revenue over the same time frame.

The NBME president’s salary is on par with what other CEOs make. But it is substantially higher than what almost any practicing physician makes in a year - especially early career MDs, from whom the bulk of those dollars were derived.

So why am I pointing all this out?

Accountability, for one thing. All nonprofit, tax-exempt organizations deserve some scrutiny to be sure that their dollars align with the organization’s mission and stakeholder values. That’s the whole reason the tax forms are public.

Accountability, for one thing. All nonprofit, tax-exempt organizations deserve some scrutiny to be sure that their dollars align with the organization’s mission and stakeholder values. That’s the whole reason the tax forms are public.

Second, the NBME operates in a strange space where normal economic forces don’t have as much gravity. Paying “customers” (i.e., students) have little choice about whether or not to buy their “product” (the USMLE), at whatever price the NBME chooses to sell it.

Lots of us criticize the for-profit test prep industry - and often, rightly so - but at least normal economic forces maintain order. If I want to make a new USMLE test prep book, I know I have to make the content better than First Aid or come in at a lower price point.

Because it has a monopoly with all state medical boards, the NBME is not easily constrained by market forces. If its leaders set an agenda for growth, it’s easy for that growth to be achieved.

Now, for those of you saying, “But the NBME is non-profit! How could they possibly be motivated by financial gain?”

Because it’s an organization made of people. Regular people. People who want to keep their jobs, or get promoted, or please their boss, or make a higher salary.

Because it’s an organization made of people. Regular people. People who want to keep their jobs, or get promoted, or please their boss, or make a higher salary.

Nonprofit organizations don’t pay taxes or return profits to shareholders. But ultimately the organization is regular individuals who are motivated by the same things that we all are.

So back to where this all got started. Moving to a pass/fail system would devalue USMLE Step 1 and ultimately lead to a substantial loss of revenue for the NBME (as fewer students and schools would be willing to pay for their non-mandatory services).

Does this strike anyone else as a potential financial conflict of interest?

To have a frank and transparent discussion about a topic that matters to so many, I would have liked to see that #COI acknowledged by Dr. @Katsufrakis in his article.

/fin

To have a frank and transparent discussion about a topic that matters to so many, I would have liked to see that #COI acknowledged by Dr. @Katsufrakis in his article.

/fin

And just in case anyone out there needs to refer a non-Twitter user to these data, I’ve posted them here:

thesheriffofsodium.com/2019/02/01/a-n…

thesheriffofsodium.com/2019/02/01/a-n…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh