I've been mulling @Clover_Health's (superficial) investor deck. While I see huge potential in MA & other value-oriented models, my TL;DR take is:

1- Nothing here clearly establishes Clover as a differentiated MA plan

2- The Direct Contracting pivot is *very* interesting 1/n

1- Nothing here clearly establishes Clover as a differentiated MA plan

2- The Direct Contracting pivot is *very* interesting 1/n

https://twitter.com/chamath/status/1313461164890677249

Caveat to all this is the startling lack of meat in the investor presentation. It is >100 pages, but most look something like this 👇, and cite only "internal company analysis."

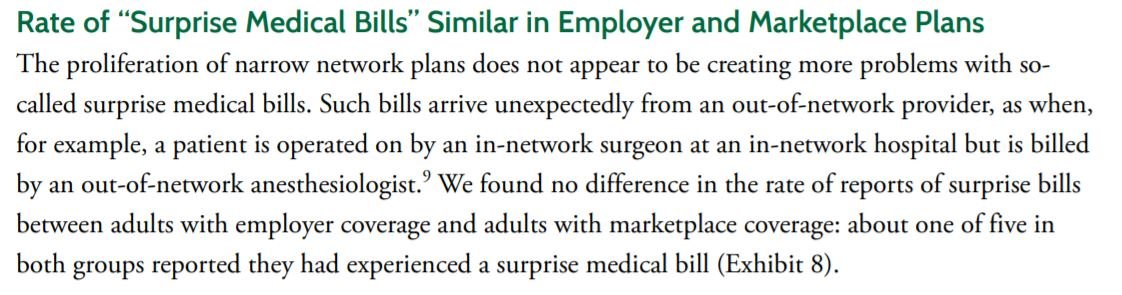

We can start by unpacking that growth. As @chamath notes, Clover had 41K MA members at the end of 2019, and the investor deck projects 57K by end-2020. So, adding a net 16,000 MA members over the course of the year.

By contrast, @Humana added ~480,000 in the year to June 2020.

By contrast, @Humana added ~480,000 in the year to June 2020.

We could also compare to a more recent MA-oriented IPO, in @OakStreetHealth, whose SEC filings show them adding ~19K members in 2019 and ~9K in the first half of 2020.

To be sure, 16K new members is material (would be ~$200M in incremental revenue), but does not seem exceptional

To be sure, 16K new members is material (would be ~$200M in incremental revenue), but does not seem exceptional

Then there is a quality question, most commonly measured via STAR ratings, which directly affect a plan's payments from CMS and enrollment growth.

Clover appears to be a 3 STAR MA insurer (overall), which sounds middling but would actually put them in the bottom 10%-ish.

Clover appears to be a 3 STAR MA insurer (overall), which sounds middling but would actually put them in the bottom 10%-ish.

Meanwhile, the deck touts a reduction in hospitalizations, relative to an un-sourced "benchmark," but it is not at all clear whether this number actually shows Clover doing better or worse than its peers.

https://twitter.com/joshk/status/1313486363497508865?s=20

For context, while the overall average number of hospitalizations (annually, per 1,000 enrollees) in traditional Medicare (aka FFS) is in the same ballpark as Clover's benchmark, there are huge variations by age, income and health status.

Oak, for example, says that it achieves a hospitalization rate of 183 per 1K members vs. a benchmark of 370. Since ~40% of Oak members are Dual eligible, 370 is prob about right.

In short, Clover looks like it has a healthier population than Oak, yet sees more hospitalizations.

In short, Clover looks like it has a healthier population than Oak, yet sees more hospitalizations.

For a non-Oak comparison, Humana's latest value-based care report claims a 29% reduction in hospitalizations relative to traditional Medicare, a figure that also seems rather better than Clover's claimed 22% reduction, though both companies are fuzzy on the baseline.

**Clover's chart isn't sourced, so unclear if they are b-marking vs. trad. Medicare or other MA plans. A possible source is this AEJ paper, which implies 252 admits/1K.

But that # is based on 2010 claims - would be dubious to compare to Clover in 2019.

web.stanford.edu/~leinav/pubs/A…

But that # is based on 2010 claims - would be dubious to compare to Clover in 2019.

web.stanford.edu/~leinav/pubs/A…

On net, Medicare Adv *is* a booming market. But it's also hotly competitive - there are ~3,000 MA plans, offered by >180 different companies, and the avg enrollee has 27 plans to choose from. Not obvious whether Clover really stands out in the crowd

As for Direct Contracting...

As for Direct Contracting...

It is striking how much Clover touts the opportunity in MA, but is really selling a Direct Contracting (DC) business.

Their projections imply that almost three quarters of their membership will be in DC vs. MA, as soon as 2021.

Their projections imply that almost three quarters of their membership will be in DC vs. MA, as soon as 2021.

This may be surprising, because DC is generally geared toward PCPs; it is arguably set up to let physician groups capture much of the margin that currently stays with MA insurers.

BUT...there's no particular reason that a carrier cannot become a "Direct Contracting Entity."

BUT...there's no particular reason that a carrier cannot become a "Direct Contracting Entity."

And, there could be real advantages to this path. Clover (and other MA plans) already have local provider networks, so can plug in add'l members. Moreover, CMS offers to act as a sort of re-insurer for DC lives, and takes on some of the admin tasks (e.g. claims adjudication).

Perhaps most interestingly, DC's voluntary attribution could shift member acquisition from PlanFinder (where a 3-STAR rating does you no favors) to the physician's office. The patient isn't choosing a new health plan, they are choosing a doctor (prob the one they already like).

All of which, I think, makes the Clover SPAC the first billion-dollar bet on Direct Contracting.

If you are buying in at a $3.7B valuation, about $2.8B of that number likely rests on the future growth and profitability of Direct Contracting, not MA. /n

If you are buying in at a $3.7B valuation, about $2.8B of that number likely rests on the future growth and profitability of Direct Contracting, not MA. /n

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh