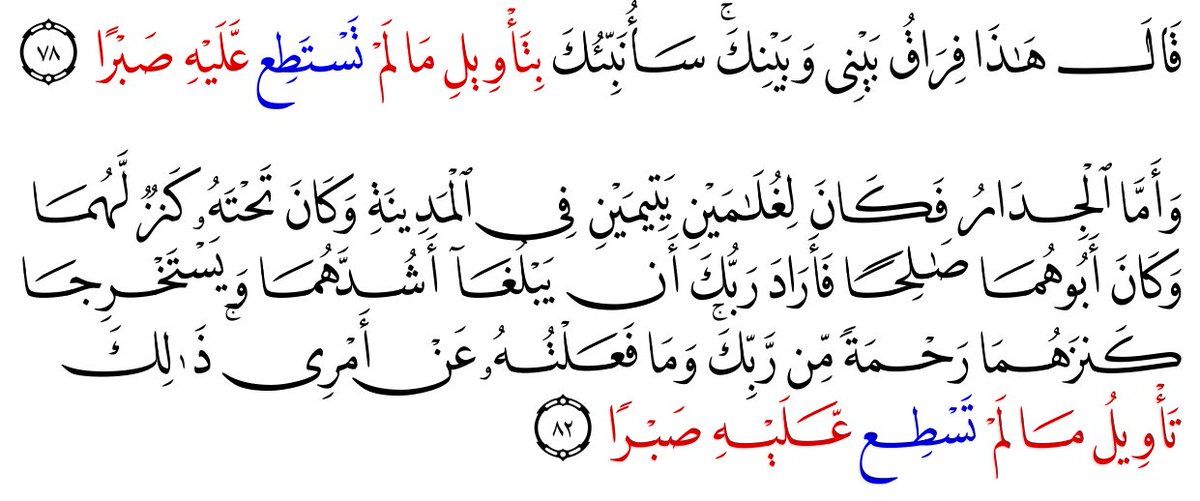

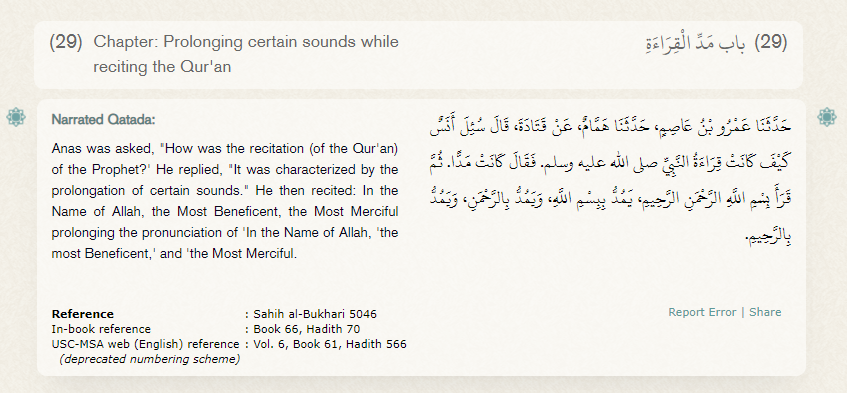

In Ṣaḥīḥ al-Buḫārī there is an interesting Hadith the claims that the prophet would have prolonged recitation, and an example is given, saying he would prolong bismi llāāh, al-raḥmāān, al-raḥīīm.

sunnah.com/bukhari/66/70

Thread on 'the prolonged reading of the prophet'. 🧵

sunnah.com/bukhari/66/70

Thread on 'the prolonged reading of the prophet'. 🧵

This hadith first caught my attention because of its incongruous nature: in Quranic recitation today, prolongation like that doesn't happen at all. In the basmalah only al-raḥīīm would be prolonged if you pause upon it and drop the final case vowels.

Me and @phillipwstokes argue on the basis of rhyme & spelling that in Quranic Arabic words lost their final case vowels not just in pause but in context as well, which would lengthen lengthening in recitation. Could this hadith be a memory of this recitation style?

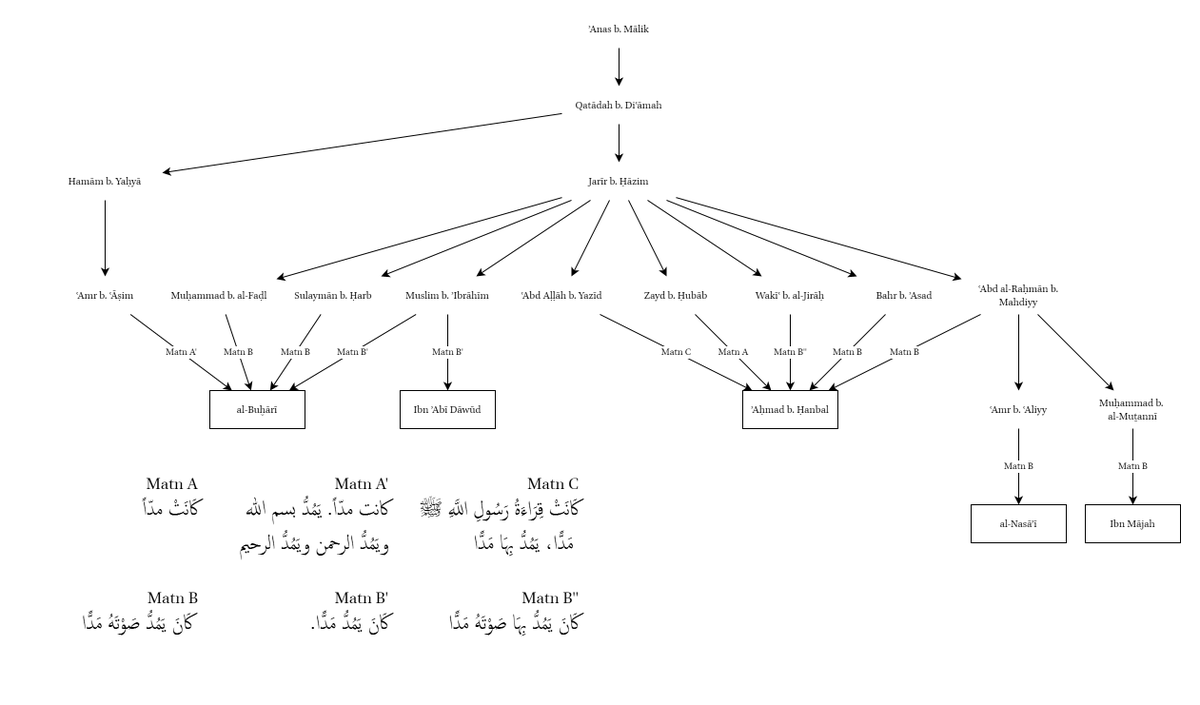

So I started tracking down versions of this Hadith to see if the wording like this is indeed ancient enough that it could be a plausible detail of a memory of the prophet's own recitation of the Quran. But it quickly becomes clear that Bukhari is the odd one out.

Other versions of the Hadith simply say the prophet's reading: kāna maddan "was stretched", kāna yamuddu maddan "used to stretched it excessively", kāna yamuddu bihā ṣawtahū maddan "used to stretch its sound excessively". But the specification of single words is Bukhari only.

Also the transmission of the Hadith is suspicious. Mapping out the different versions of this Hadith, with the wording a clear pattern emerges. The main wording of this hadith is kāna yamuddu ṣawtahū maddan, which consistently traces back to Jarīr b. Ḥāzim as the common link.

There are two fairly solid partial common links below him: ʿAbd al-Raḥmān b. Mahdiyy who seems to transmit the exact same wording. The other is Muslim b. ʾIbrāhīm who transmits a slightly abbreviated version (kāna yamuddu maddan).

Jarīr b. Ḥāzim as the spreader of the Hadith is extremely well-established, he forms the common link, and we can be certain that he is the one who spread the Hadith. The long version of Bukhari is a classic "dive".

It connects to an earlier authority with anomalous contents.

It connects to an earlier authority with anomalous contents.

With this isolated chain of transmission and its anomalous contents, it is difficult to take the account as historical. Even if it was (which I doubt). there is simply no way to corroborate it. Too bad, as I would like it as evidence for my reconstruction of Quranic Arabic.

All the reliable part part of this hadith tells us, then is that Jarīr b. Ḥāzim claims to have heard that the prophet used to "stretch out the sound". A frustratingly vague description, which was probably the reason for the explanatory expansion of the hadith to be forged.

If you want to read more about the case system of Quranic Arabic base on the Quranic Consonantal text, check out our article here:

academia.edu/37481811/Case_…

academia.edu/37481811/Case_…

If you enjoyed this thread and want me to do more of it, please consider buying me a coffee.

ko-fi.com/phdnix.

If you want to support me in a more integral way, you can become a patron on Patreon!

patreon.com/PhDniX

ko-fi.com/phdnix.

If you want to support me in a more integral way, you can become a patron on Patreon!

patreon.com/PhDniX

@threadreaderapp unroll

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh