When were the first human #coronaviruses (CoVs) discovered and studied?

How were these viruses associated with human #disease?

It's time to learn our history about human CoVs, and the scientists and volunteers that allowed us to identify this new group of viruses.

A THREAD.

How were these viruses associated with human #disease?

It's time to learn our history about human CoVs, and the scientists and volunteers that allowed us to identify this new group of viruses.

A THREAD.

Mid-sixties: HCoV-229E and HCoV-OC43 were identified.

1. Hamre et al. (1966)

2. McIntosh et al. (1967)

3. Tyrrell et al. (1965).

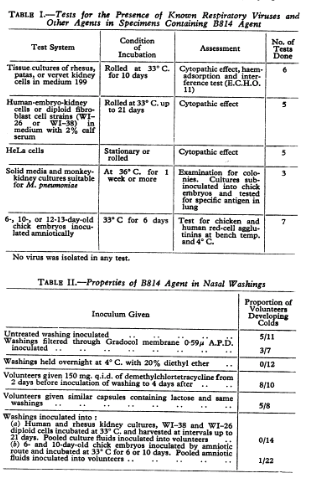

Image: Tyrrell et al. (1965).

1. Hamre et al. (1966)

2. McIntosh et al. (1967)

3. Tyrrell et al. (1965).

Image: Tyrrell et al. (1965).

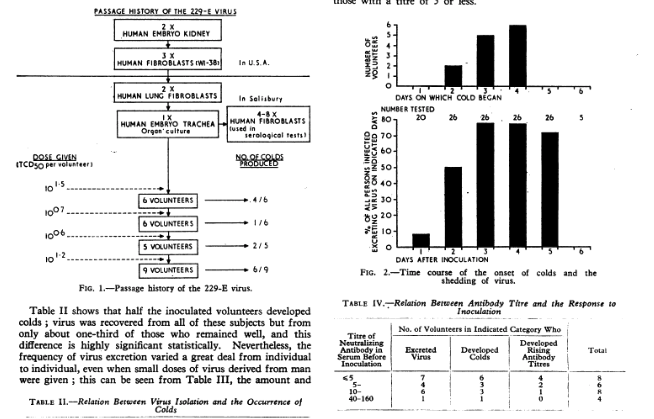

Healthy HUMAN volunteers were infected to demonstrate that 229E and OC43 resulted in a common cold.

1. Bradburne et al. (1967, 1972)

2. Hamre et al. (1966)

Image: Bradburne et al. (1967)

1. Bradburne et al. (1967, 1972)

2. Hamre et al. (1966)

Image: Bradburne et al. (1967)

Both 229E and OC43 were considered harmless or low pathogenic for humans.

This changed when #SARSCoV emerged in November 2002. This new #CoV caused severe respiratory disease.

1. Peiris et al. (2003): nejm.org/doi/full/10.10…

This changed when #SARSCoV emerged in November 2002. This new #CoV caused severe respiratory disease.

1. Peiris et al. (2003): nejm.org/doi/full/10.10…

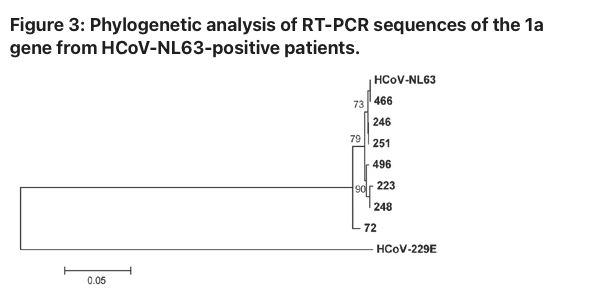

Later, two additional #CoVs were discovered in humans.

1. HCoV-NL63 (van der Hoek et al., 2004)

2. HCoV-HKU1 (Woo et al., 2005)

Image: van der Hoek et al. (2004)

1. HCoV-NL63 (van der Hoek et al., 2004)

2. HCoV-HKU1 (Woo et al., 2005)

Image: van der Hoek et al. (2004)

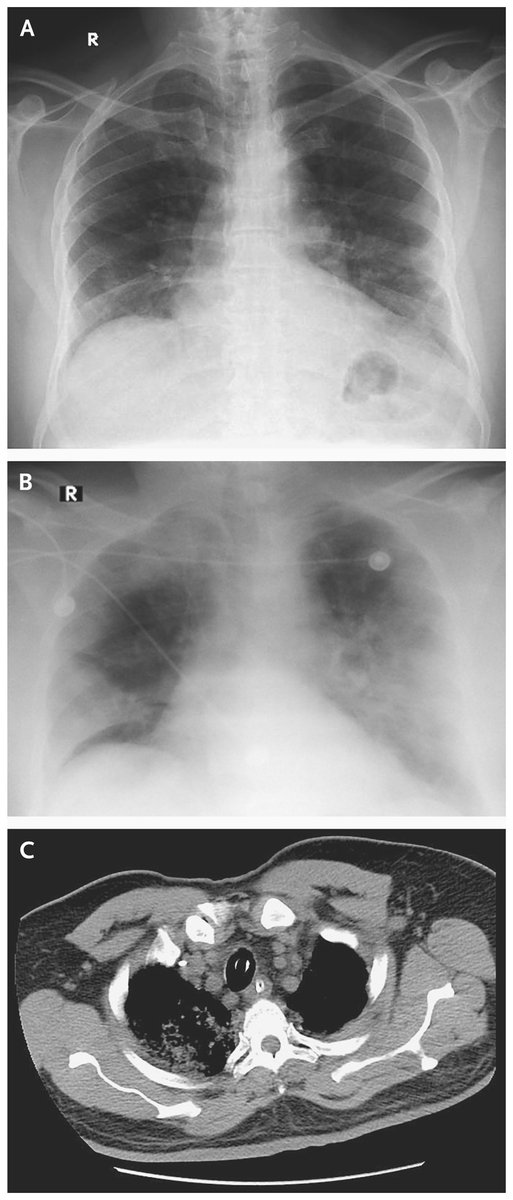

These were followed by #MERSCoV and #SARSCoV2 in 2012 and 2019, respectively.

1. MERSCoV first report: Zaki et al. (2012)

2. #SARSCoV2 first report: Zhou et al. Nature, 2020 (but there could be other simultaneous reports)

Image: Zaki et al. NEJM (2012)

1. MERSCoV first report: Zaki et al. (2012)

2. #SARSCoV2 first report: Zhou et al. Nature, 2020 (but there could be other simultaneous reports)

Image: Zaki et al. NEJM (2012)

I still have questions about why some human CoVs are low pathogenic, while others cause more severe disease. Site of replication? Ease of transmission/immune modulation? Feel free to chime in.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh