Campaign Against Italy Nonsense:

I receive comments such as: Ok, I get your data, but what can we do to make this work? A thread with ideas on achieving North-South convergence and making the €zone work for all countries /1

socialeurope.eu/keeping-the-pr…

#CAIN

I receive comments such as: Ok, I get your data, but what can we do to make this work? A thread with ideas on achieving North-South convergence and making the €zone work for all countries /1

socialeurope.eu/keeping-the-pr…

#CAIN

In its current architecture, the eurozone is a web of glass—superficially stable, but brittle when subject to shocks. To avoid a break-up and render it resilient for the long term, the sources of this fragility must be identified and remedied. /2

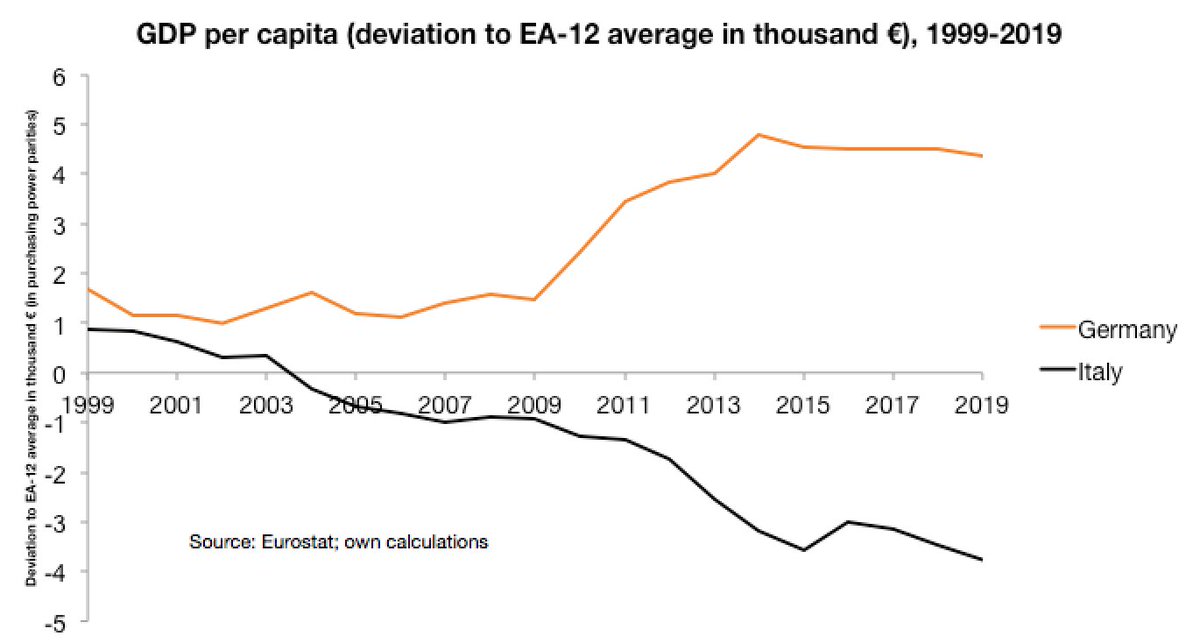

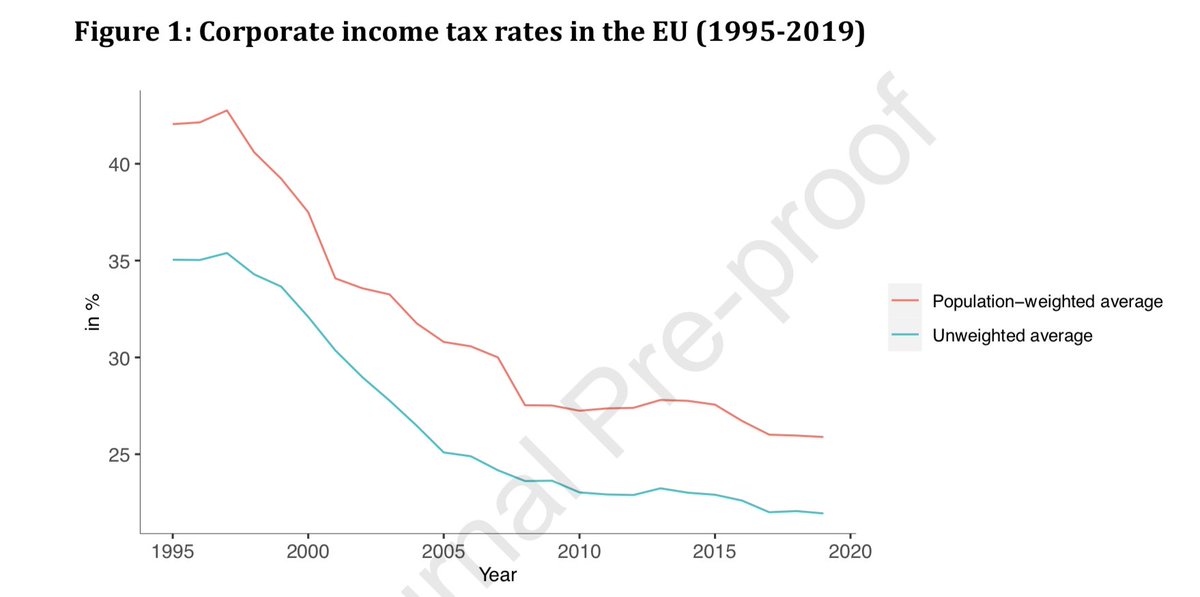

The reasons for the €Z’s fragility are essentially political; technical solutions have been on the table for years. There is a lack of intergovernmental trust, especially in the North, and a lack of legitimacy in the eyes of the population, especially in the South. /3

That's why I am so vocal in criticising nonsense about Italy and Southern Europe. If we don't increase trust, necessary projects won't get off the ground. /4

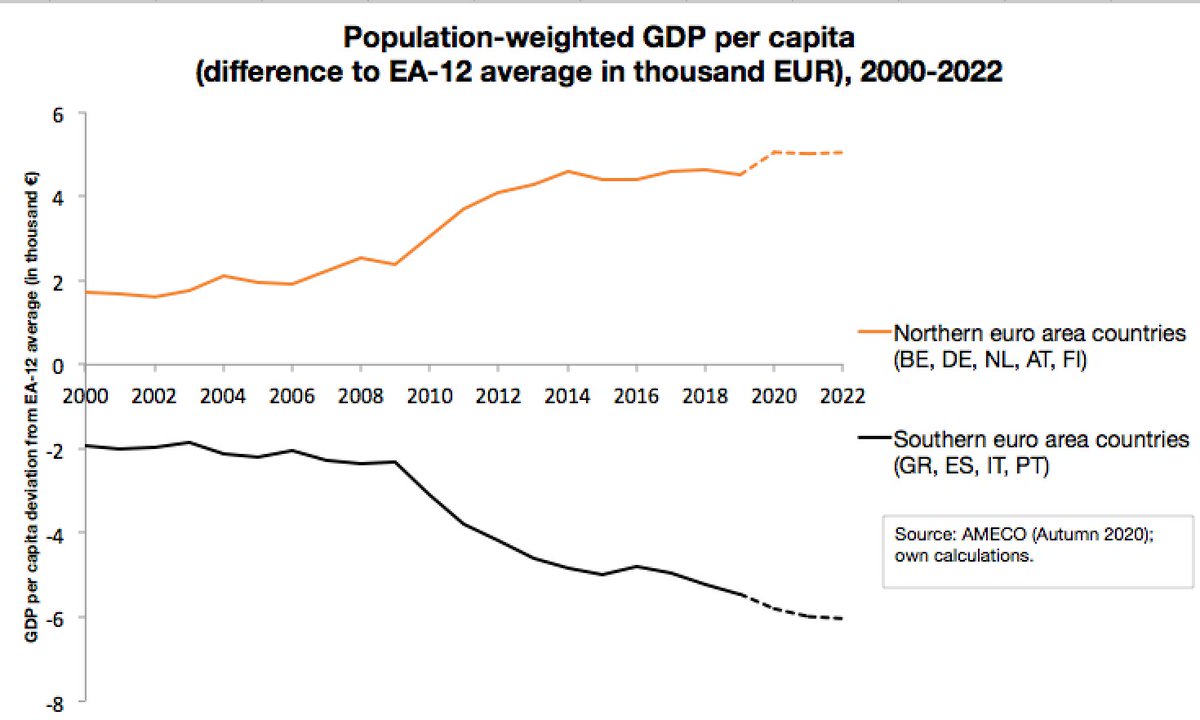

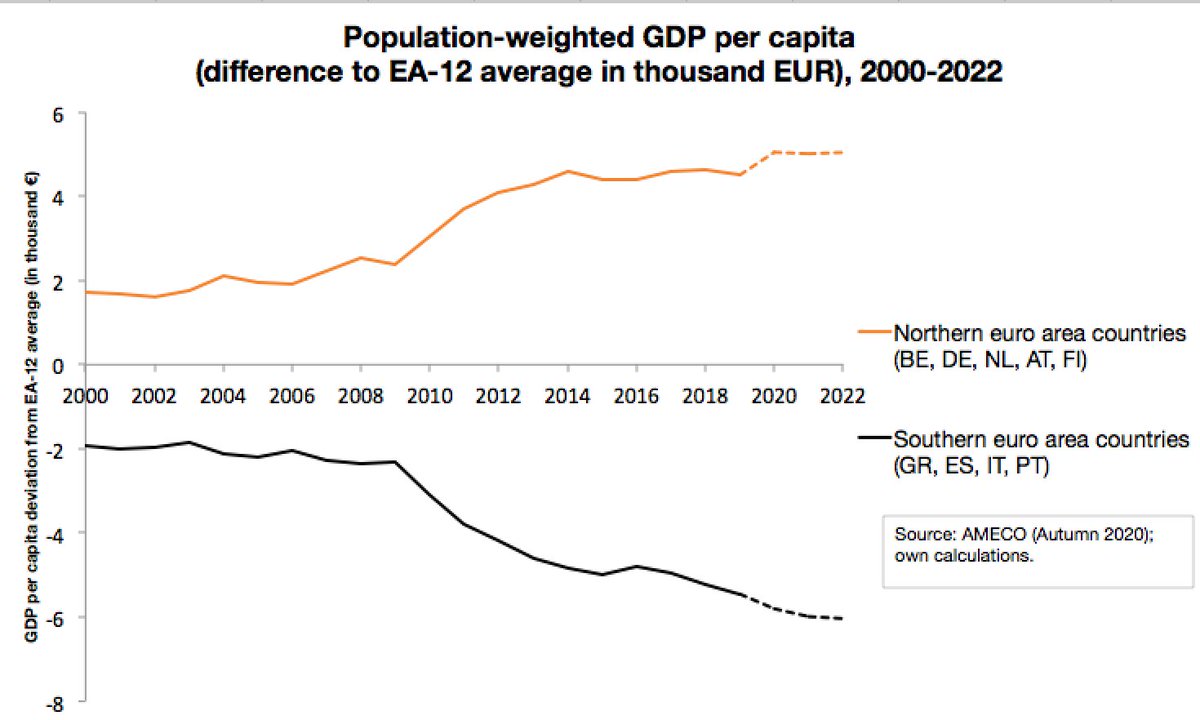

The € was linked to the promise of "prosperity for all" - which has not materialised. We must say this if we want to improve: per capita incomes in Northern and Southern €countries have drifted further apart; there are large regional differences within individual countries. /5

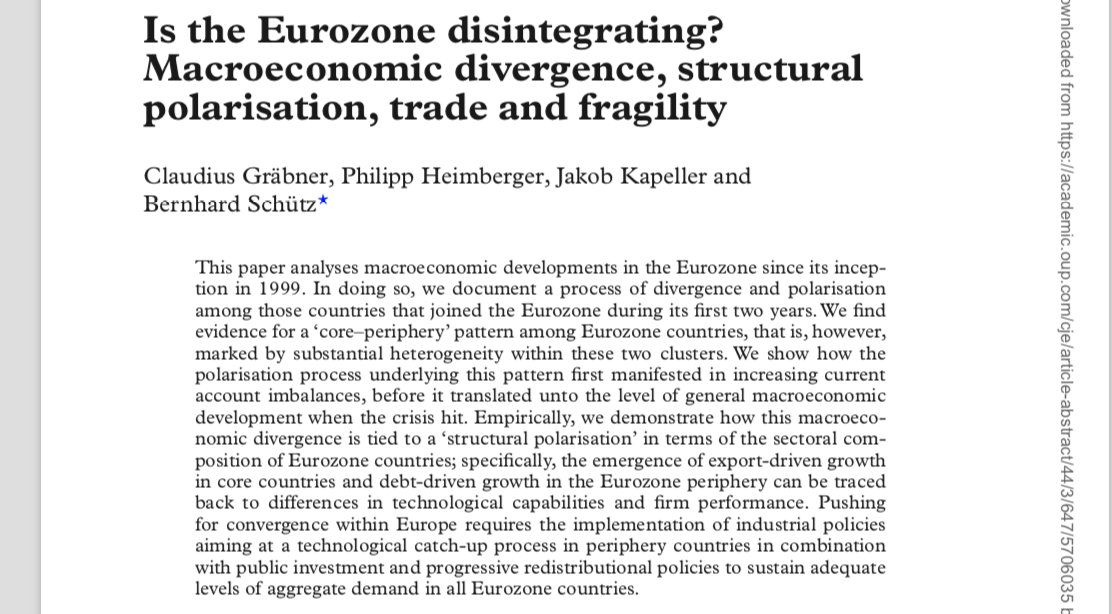

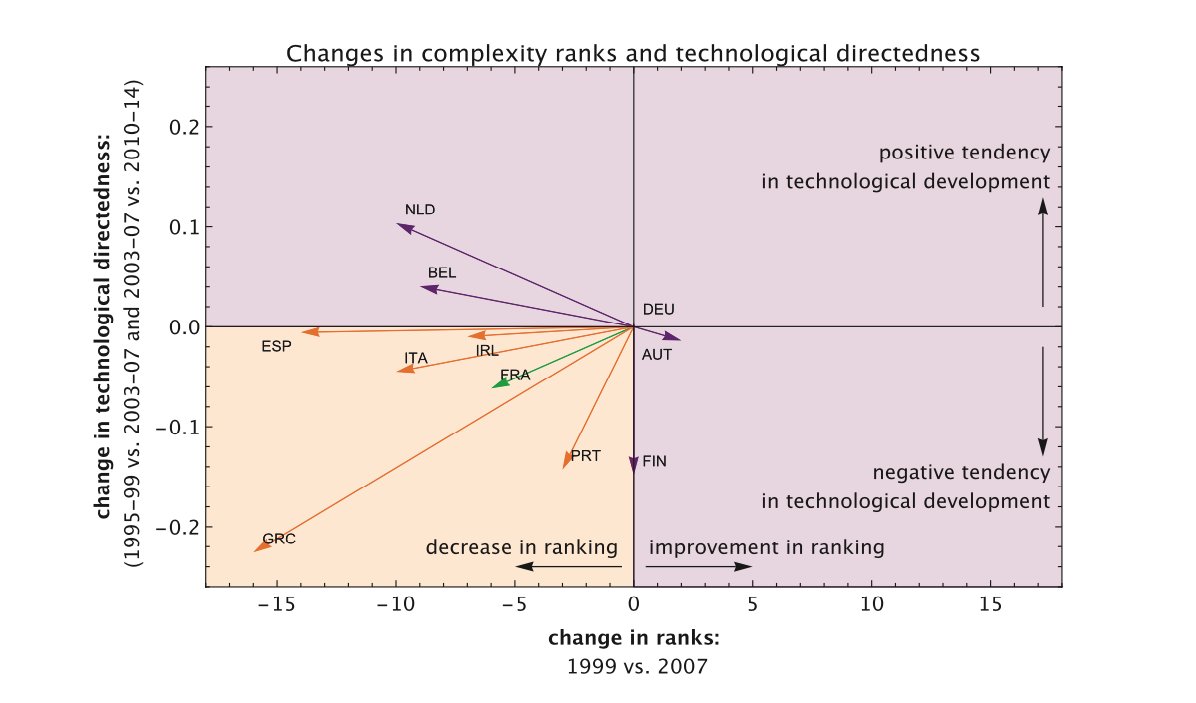

Economics helps explain why the member states are diverging. Successful companies tend to cluster in areas with lots of other high-productivity, high-value-adding companies. /6

academic.oup.com/cje/article/44…

academic.oup.com/cje/article/44…

Even though wages, rents and other costs may be lower elsewhere, companies prefer clusters because they offer strong regional labour markets, supplier and customer networks, research-and-development spillovers and other synergies. /7

Structural advantages have allowed the countries in the North to increase their lead since the euro was founded. At the same time, the convergence of living standards - although postulated as a goal - has never been a real priority of European economic policy in practice /8

A promising way forward is to reaffirm the promise of convergence and match the words of yesterday with the actions of tomorrow. Only thus can trust be restored and the euro endure. /9

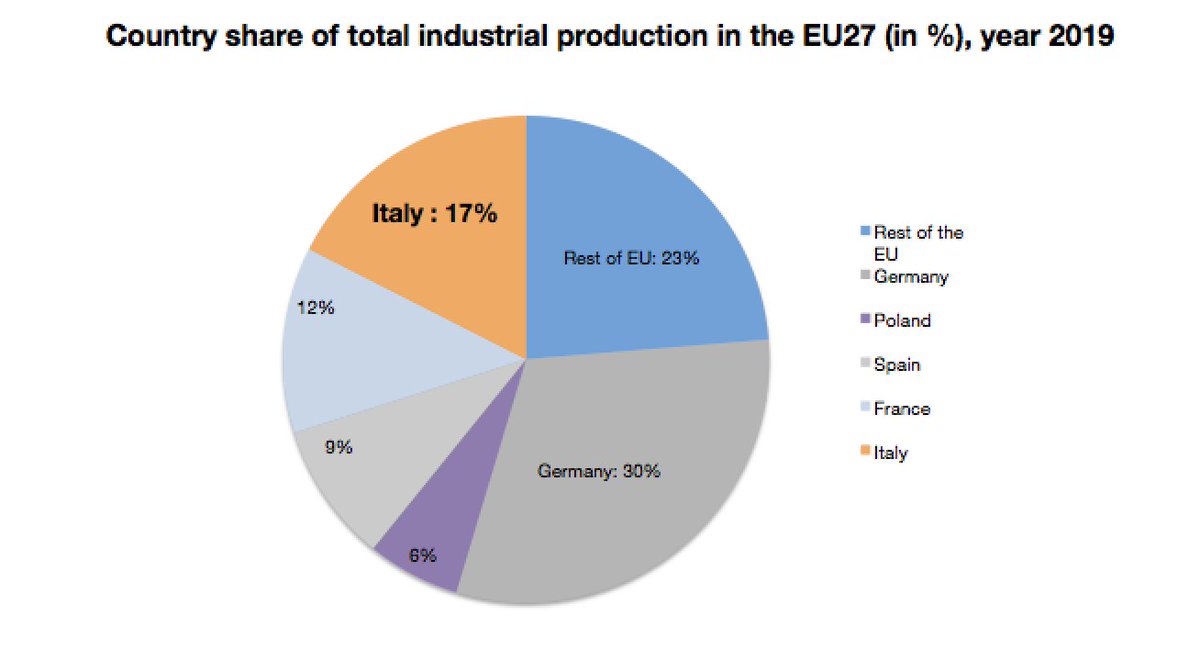

But: fostering convergence through permanent fiscal transfers is neither politically nor economically viable. Even in the past, proposals along these lines failed to find majority support; there is little to suggest this will change after coronavirus crisis. /10

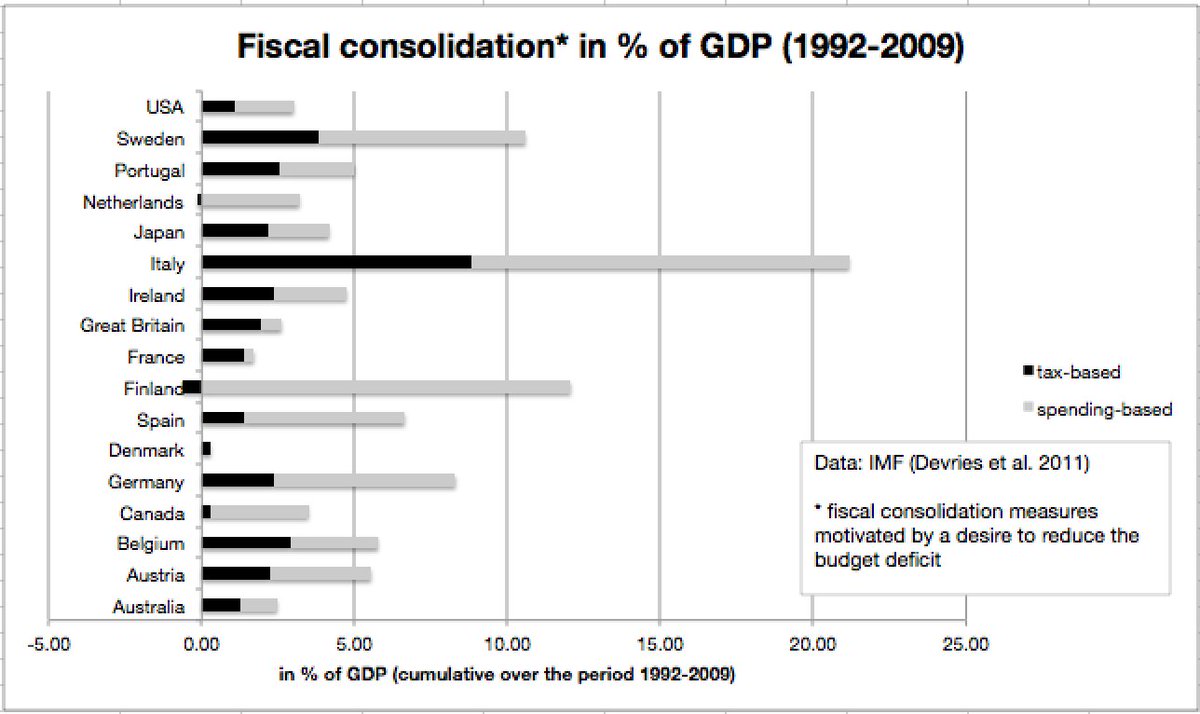

It is good that we have the EU recovery fund given the size of the shock. And I'm in favour of developing it into a permanent fiscal capacity to allow for macroeconomic stabilisation in future crises. But such an instrument can't break the underlying path-dependent divergence /11

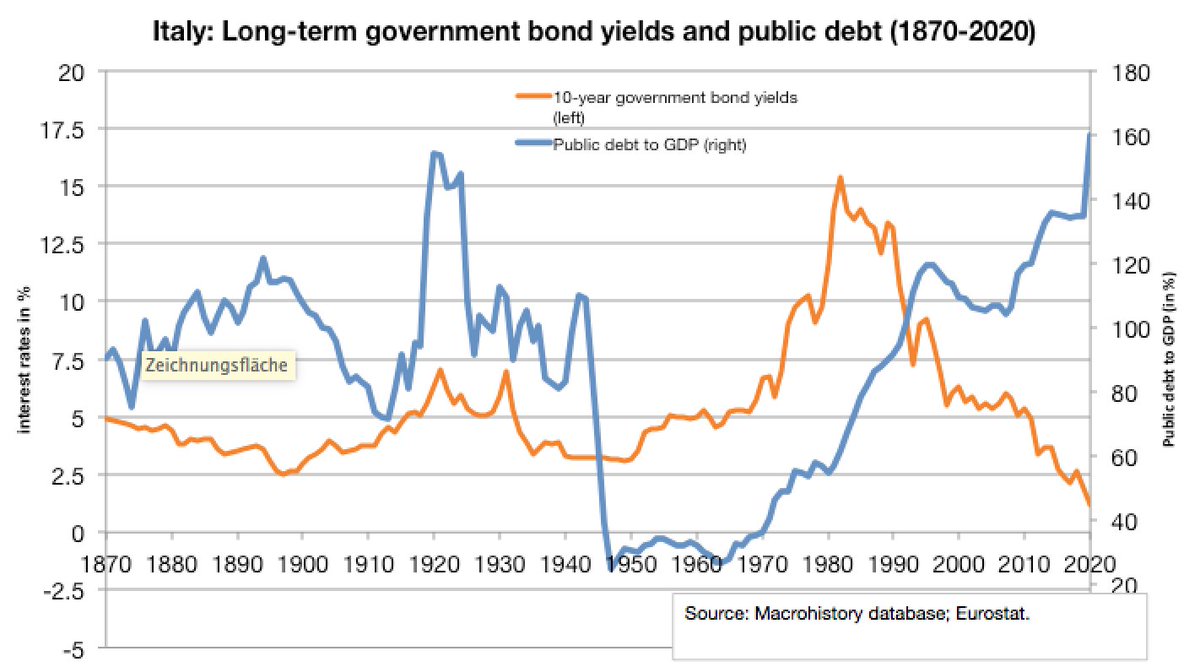

Permanent transfers are not a solution. Within-country experiences in Germany and Italy show that income transfers alone—whether through pensions, unemployment insurance or welfare payments—do not lead to underlying economic convergence among regions. /12

A more promising approach is to even out the regional distribution of value added. Andalusia, the Uckermark and metropolitan areas such as Naples or Thessaloniki should be brought to similar levels of productivity as Munich, Milan or the Amsterdam metropolitan area. /13

The tools exist: a European industrial strategy; targeted investments in infrastructure, research and development and key technologies; a rethink of European Central Bank policy, possibly with regional differentiation; a European investment budget deserving of the name. /14

All these instruments could help upward convergence across the regions, not by redistributing the fruits of growth but by spreading economic activity more evenly. /15

Just as the United States government has strengthened the Silicon valley through public investment, particularly in high technology, structurally weak parts of the eurozone could be promoted through similar approaches. /16

A European industrial policy could deliberately place parts of green and strategic value chains—battery production, medical supplies or green mobility—in structurally disadvantaged regions. Public procurement, e.g. for high-value products, could be used just as strategically. /17

All this requires us to be optimistic and bold, and to refrain from self-fulfilling pessimism. Repeating the old mantras (e.g. more fiscal consolidation pressure and labour market liberalisation for Italy) won't solve the major problems after COVID. /18

In any case, the future of the €zone requires a political decision: either we abandon the euro’s promise after COVID or we recommit to it. If the latter, then a mission-oriented political and economic convergence project must follow. /19

This requires us to work with Italy, the third-largest €zone economy and the second-largest industrial location. We would lose so much strength for all our future European projects if we were to lose Italy due to self-fulfilling pessimism. /end

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh