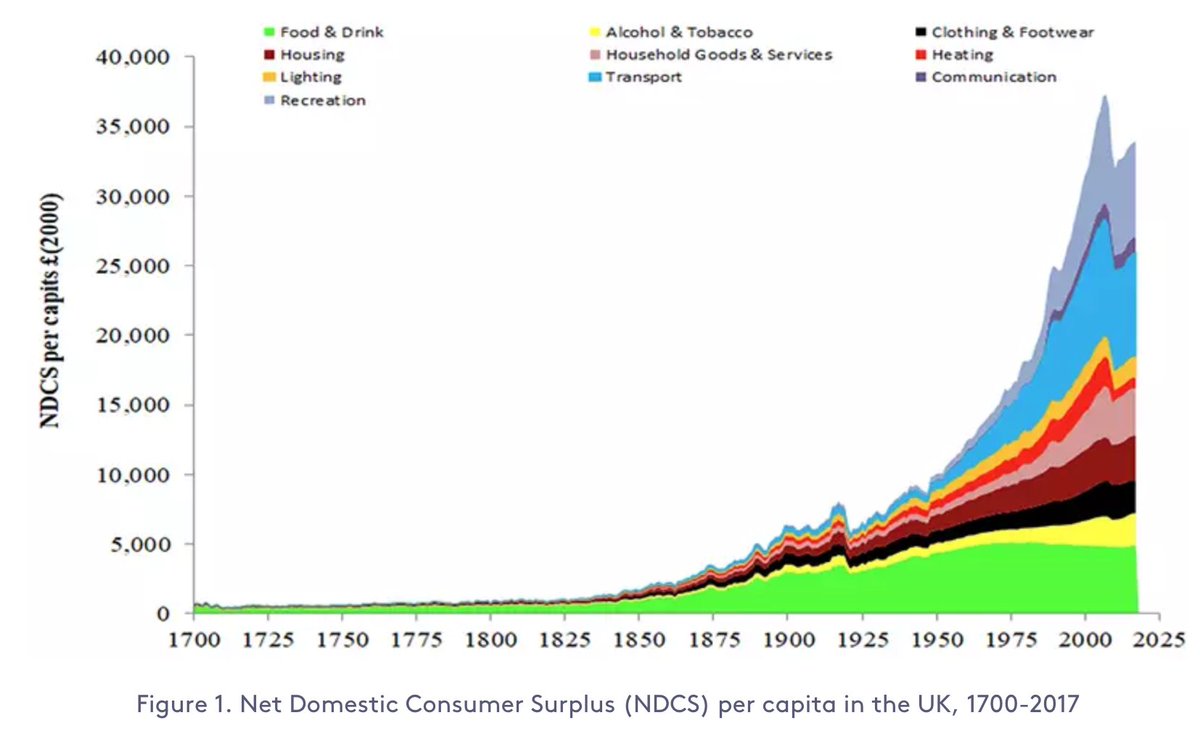

A chart from a very interesting, ongoing research project of Roger Fouquet at the LSE lse.ac.uk/granthaminstit…

He estimates the 'Net Domestic Consumer Surplus' – as a measure of economic welfare to complement GDP – for the UK over the last 300 years.

He estimates the 'Net Domestic Consumer Surplus' – as a measure of economic welfare to complement GDP – for the UK over the last 300 years.

It's a very ambitious project – he has to do extensive historical data work to reconstruct the consumption of goods and services over the last three centuries.

As Roger mentions in the link above, he is looking for funding to finish this work.

Do you know a person or an institution that would be interested to fund this research project?

If so, let him know – his email is at the link.

Do you know a person or an institution that would be interested to fund this research project?

If so, let him know – his email is at the link.

This research is what I was looking for when I was asking whether someone had ever tried to evaluate a kind of whole economy consumer surplus.

At the time no one knew of a project like this – Roger seems to be the first one who is doing it!

At the time no one knew of a project like this – Roger seems to be the first one who is doing it!

https://twitter.com/MaxCRoser/status/1373311631237713922

cc'ing some of the people who were part or mentioned in that discussion on this back in March: @jdportes @AngelLamuno @TimHarford @edavidds @erikbryn @benshaaaw @Noahpinion @GRobLewis @Peter_0_0_g @edavidds

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh