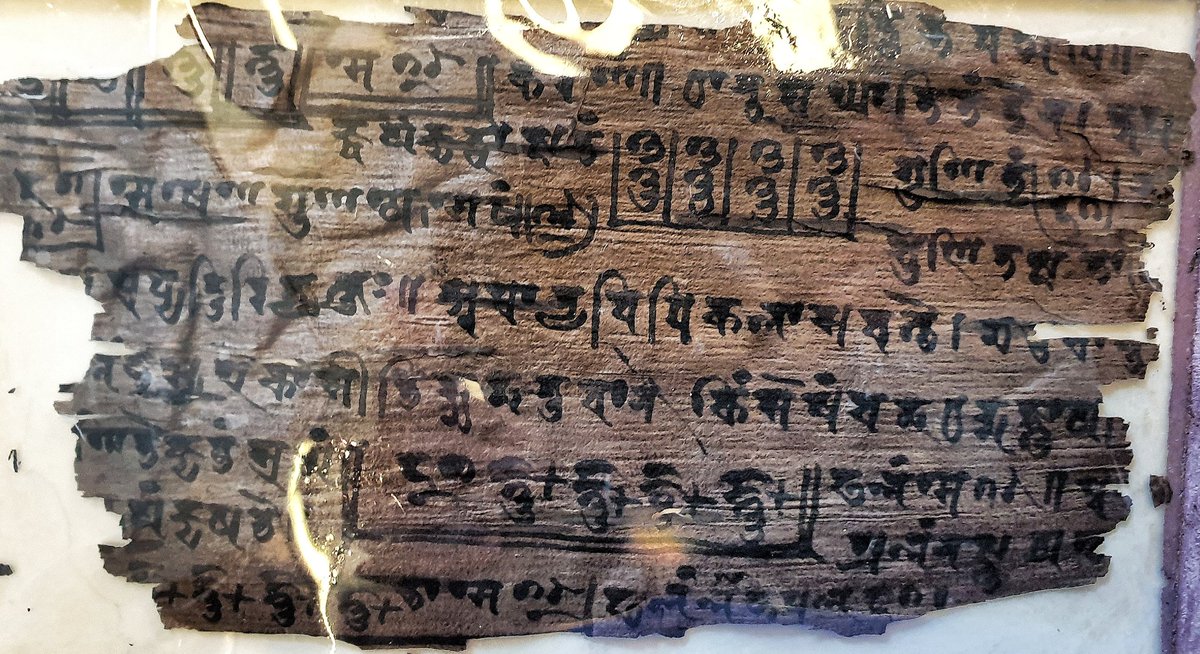

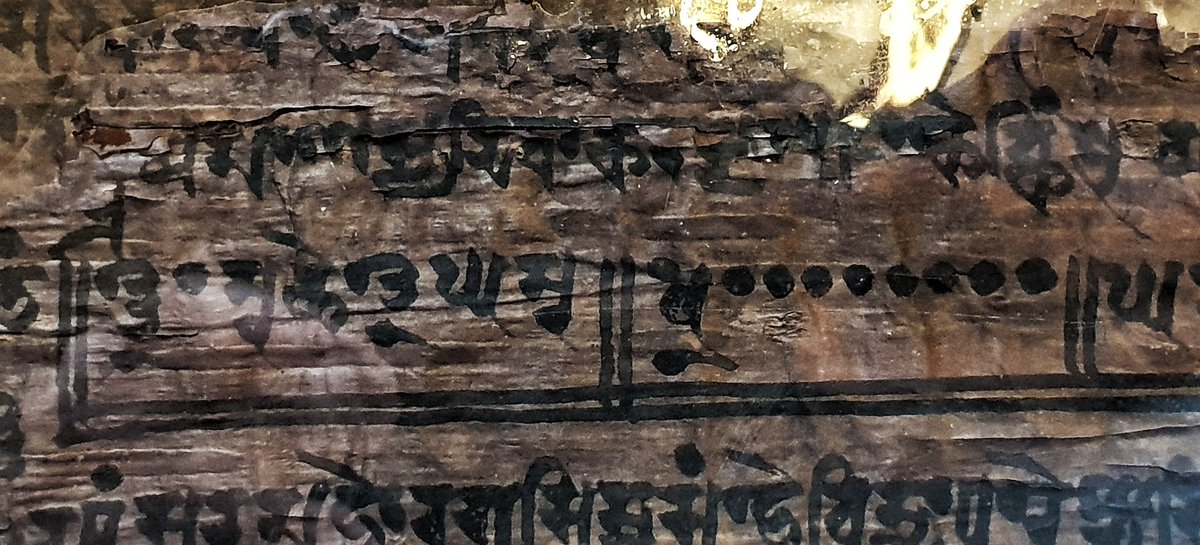

The Bakhshali Manuscript, now in the Bodleian Library, is by many centuries the oldest surviving Indic mathematical text and the oldest extant manuscript in the world to use zero and decimal place values.

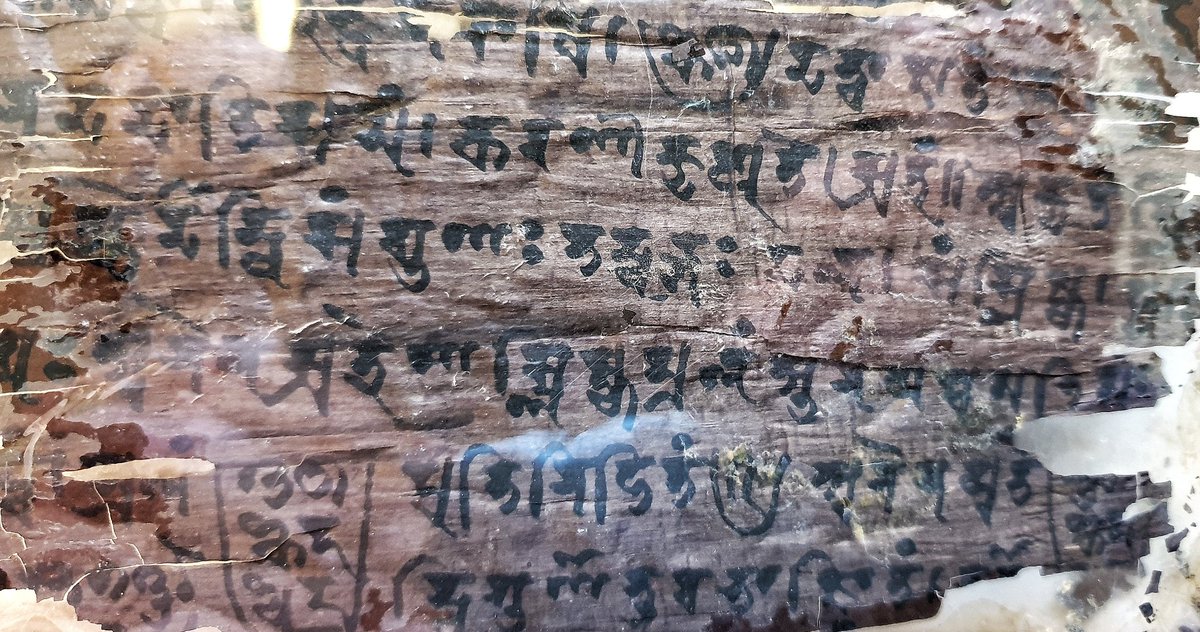

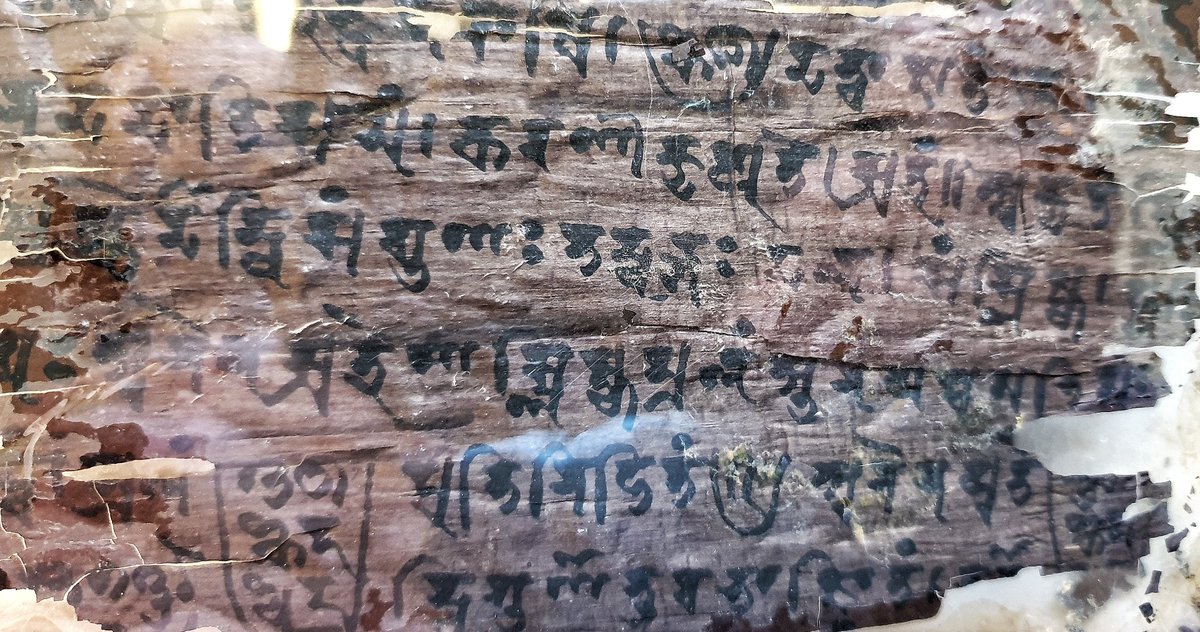

This remarkable birch bark manuscript consists of 70 extremely fragile folios. It has been the subject of scholarly debates over its date, its purpose, the religious world inhabited by its writers & the question if whether it is unitary text or a collection of different treatises

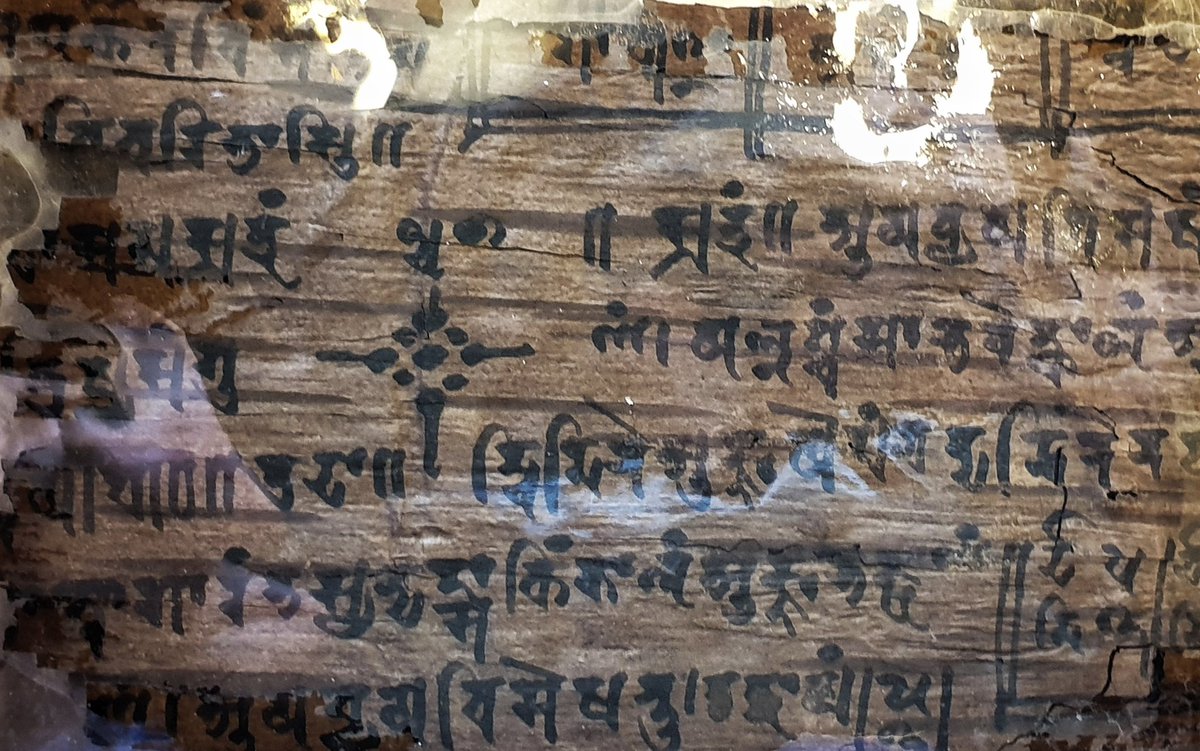

Over the years, the dates proposed for the Bakhshali manuscripy vary from the third to the twelfth centuries CE, but it is currently thought to have been written around 700CE, a date recently confirmed by a new set of carbon C-14 dates.

Found in 1882 buried in a field 80 kms away from Peshawar, near the village of Bakhshali, it is written in Sanskrit but in a form that has been strongly influenced by the vernaculars of the region. The script is sarada, a North Indian descendant of Gupta Brahmi.

As the Government Palaeographer of India, A. F. R. Hoernle, reported it was “... found in a ruined enclosure, near Bakhshálí, a village of the Yusufzai District, by a man who was digging for stones... " Unfortunately, most of the mss was destroyed at the time of its discovery

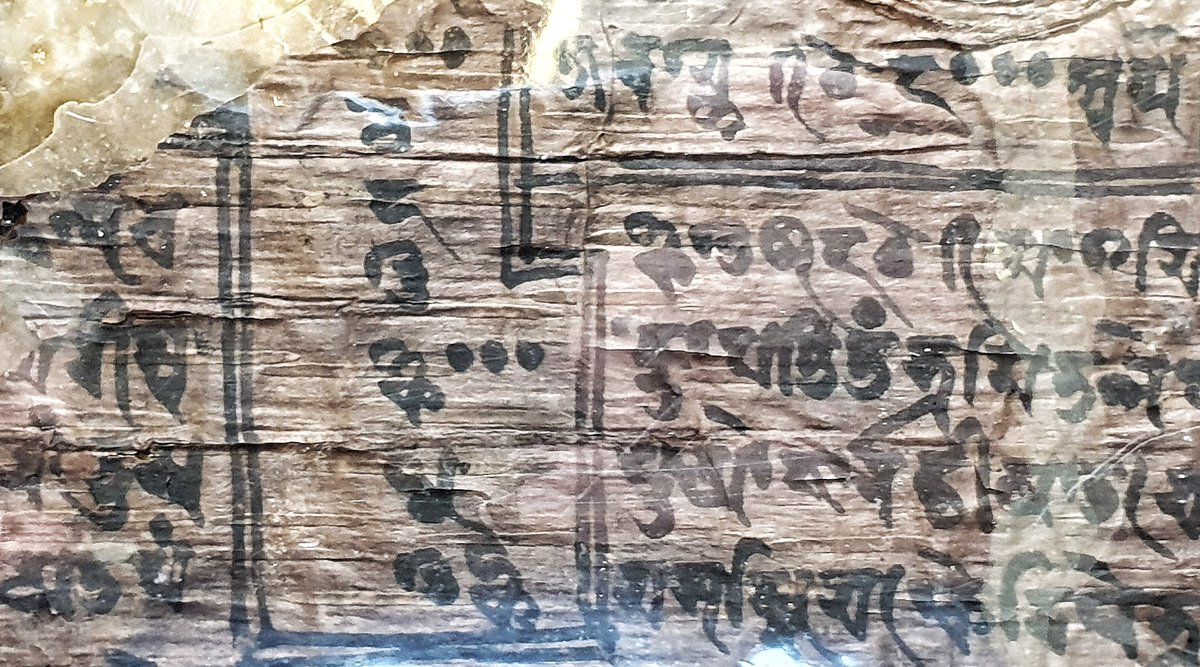

It is a hybrid Sanskrit compendium of mathematical formulas, algorithms and examples, in the form of verse rules or sutras and sample problems mixed with a prose commentary.

It contains a collection of several dozen algorithims and mathematical problems in verse, with a commentary explaining them in a combination of prose and numerical notation.

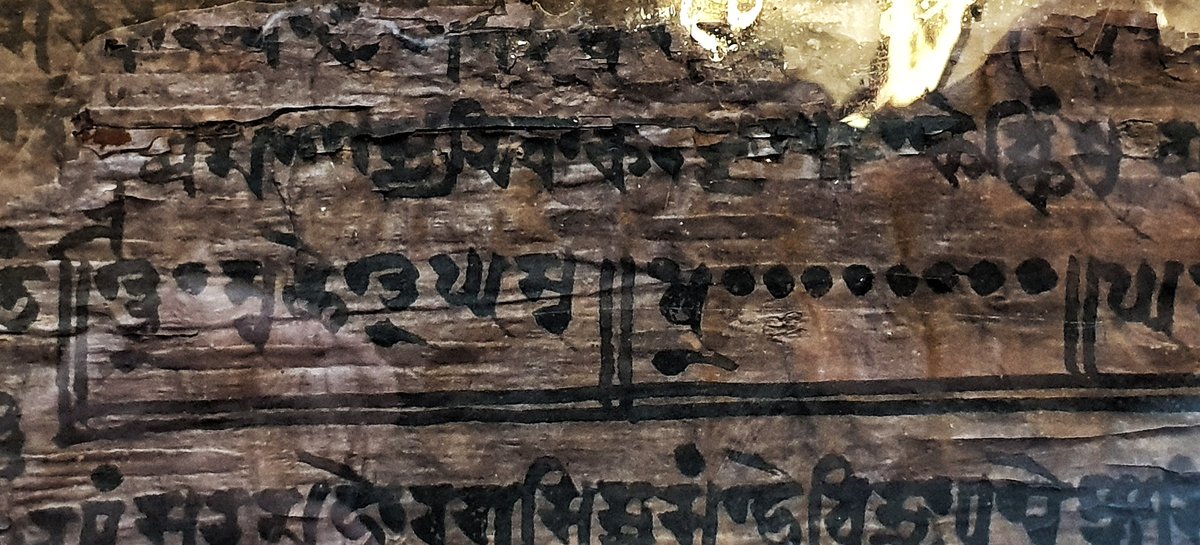

It uses decimal place value, negative numbers, fractions, square roots, and the earliest zero of any known manuscript, represented by a large round dot.

The zeros function as arithmetical operators, i.e., as numbers in their own right, and not merely as place-holder digits; they also represents Unknowns.

The manuscript shows similarities to the 629CE commentary on the Aryabhatiya by the 7thC mathematician, Bhaskara I. This seems to indicate that both works belong to a similar period, although some of the rules and examples in the Bakhshalı may date from earlier periods.

Some probably erroneous c14 put the mss as early as 200AD, but that date has been strongly resisted by most serious scholars who say that the paleography and quasi-codex form date it firmly from c650--900CE, a date supported by the new and more comprehensive set of carbon dates.

A colophon says it was written by an anonymous Brahmin identified as the son of Chajaka and a “king of calculators.” He says he wrote for the use of one “Hasika son of Vasiṣṭha” and his descendants, in a locality probably called Mārtikāvatī in the Gandhāra region.

The manuscript’s consistency of appearance has produced the generally accepted (though far from final) conclusion that it is a single work written by one hand, with a second hand seen in a single portion

Chajaka seems concerned with practical tasks like weighing metal, the composition of alloys and impure metals, refiing and working out losses in raw materials through smelting. He therefore seems to have been in the metal trade.

If anyone is interested in learning more,

The Bakhshali Manuscript by Takao Hayashi is a good place to start and, more generally, Kim Plofker's brilliant Mathematics in India, which has a superb chapter on the Bakhshali. Also George Gheverghese Joseph's The Crest of the Peacock.

The Bakhshali Manuscript by Takao Hayashi is a good place to start and, more generally, Kim Plofker's brilliant Mathematics in India, which has a superb chapter on the Bakhshali. Also George Gheverghese Joseph's The Crest of the Peacock.

The Bakhshali manuscript will also be a centrepiece of my next book, The Golden Road, about the diffusion of Indic civilization from 200BCE

'From 200 BC to 1200 AD, India was a confident exporter of its own civilisation in all its forms’ cntraveller.in/story/200-bc-1… via @CNTIndia

'From 200 BC to 1200 AD, India was a confident exporter of its own civilisation in all its forms’ cntraveller.in/story/200-bc-1… via @CNTIndia

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh