This🧵is about a tricky problem in education

The problem: despite growing global wealth and technological progress, there are extremely poor parts of the world where most children grow up illiterate and innumerate

We have two new papers showing that this can be changed

1/n

The problem: despite growing global wealth and technological progress, there are extremely poor parts of the world where most children grow up illiterate and innumerate

We have two new papers showing that this can be changed

1/n

Here are the papers, one in the Journal of Development Economics

(sciencedirect.com/science/articl…)

and one in the Journal of Public Economics (sciencedirect.com/science/articl…)

Our tl;dr message:

2/n

(sciencedirect.com/science/articl…)

and one in the Journal of Public Economics (sciencedirect.com/science/articl…)

Our tl;dr message:

2/n

The problem: most prior research finds that the best we could hope for from educational interventions in these places is small to medium learning gains

We show: with the right inputs, we can achieve much larger learning gains in these places than previously thought possible

3/n

We show: with the right inputs, we can achieve much larger learning gains in these places than previously thought possible

3/n

Specifically, we report two #RCT studies showing that

highly resourced, bundled interventions

can teach children in extremely poor and hard to reach places to read fluently and do basic math very well

Places where, otherwise, very few people will ever gain these skills

4/n

highly resourced, bundled interventions

can teach children in extremely poor and hard to reach places to read fluently and do basic math very well

Places where, otherwise, very few people will ever gain these skills

4/n

In this thread, I’ll give highlights from both papers

If you don’t make it to the end, a few talking points:

1) In many of these hard-to-serve parts of low income countries, the counterfactual is most children growing up without the ability to read or do simple arithmetic

5/n

If you don’t make it to the end, a few talking points:

1) In many of these hard-to-serve parts of low income countries, the counterfactual is most children growing up without the ability to read or do simple arithmetic

5/n

2) This is despite the fact that enrollment in school and attendance of teachers and children are often high

3) 100s of studies of #education in low income countries study interventions to change supply, #edtech, teacher incentives, student incentives, many other things...

6/n

3) 100s of studies of #education in low income countries study interventions to change supply, #edtech, teacher incentives, student incentives, many other things...

6/n

These can increase learning, but usually only modestly – often in the 0.1-0.4 SD range

These are summarized in the great systematic reviews and meta-analyses by @karthik_econ, @DaveEvansPhD, @Yuan_Fei_ @aganimian, Patrick McEwan, Paul Glewwe, Michael Kremer, many others

7/n

These are summarized in the great systematic reviews and meta-analyses by @karthik_econ, @DaveEvansPhD, @Yuan_Fei_ @aganimian, Patrick McEwan, Paul Glewwe, Michael Kremer, many others

7/n

But, as Lant Pritchett points out in his book “The Rebirth of Education”:

even combining several of these together, assuming their effects were additive

would yield only (relatively) small learning gains, leaving millions of children behind

8/n

even combining several of these together, assuming their effects were additive

would yield only (relatively) small learning gains, leaving millions of children behind

8/n

In these two papers, my coauthors and I answer the following question:

if we combine multiple interventions

in a way that educators think will make a difference, and has enough resources that it *can* really make a difference

How much good can we do?

The answer: a lot

9/n

if we combine multiple interventions

in a way that educators think will make a difference, and has enough resources that it *can* really make a difference

How much good can we do?

The answer: a lot

9/n

The first study is:

“How much can we remedy very low learning levels in rural parts of low-income countries? Impact and generalizability of a multi-pronged para-teacher intervention from a cluster-randomized trial in The Gambia”

sciencedirect.com/science/articl…

10/n

“How much can we remedy very low learning levels in rural parts of low-income countries? Impact and generalizability of a multi-pronged para-teacher intervention from a cluster-randomized trial in The Gambia”

sciencedirect.com/science/articl…

10/n

The Gambia is a small West African country; its per-capita GDP ranks in the bottom 20 of countries. Literacy is also very low: <64% for males, <48% for females

We worked in small villages in the interior of the country, where income and learning levels are even lower.

11/n

We worked in small villages in the interior of the country, where income and learning levels are even lower.

11/n

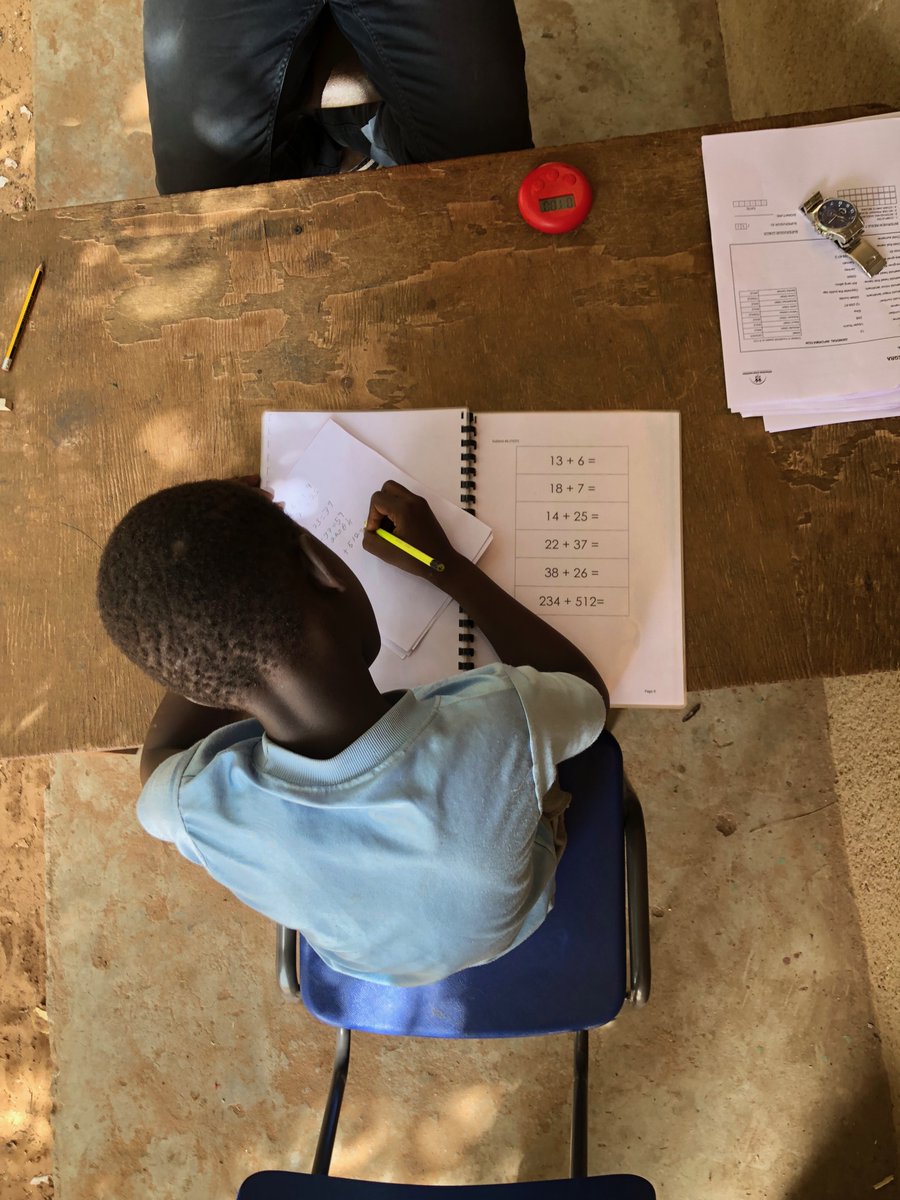

We ran a #RCT to evaluate an after-school multi-pronged intervention for kids in grades 1-3. The intervention

- hired people from nearby who were previously untrained as teachers (para teachers)

- trained them to teach remedial, after school classes using scripted lessons

12/n

- hired people from nearby who were previously untrained as teachers (para teachers)

- trained them to teach remedial, after school classes using scripted lessons

12/n

- monitored teachers, and student learning, closely

- provided enough resources (funding, support) to make the system work.

It ran for three years, at the end of which we tested children using standard literacy and numeracy tests

13/n

- provided enough resources (funding, support) to make the system work.

It ran for three years, at the end of which we tested children using standard literacy and numeracy tests

13/n

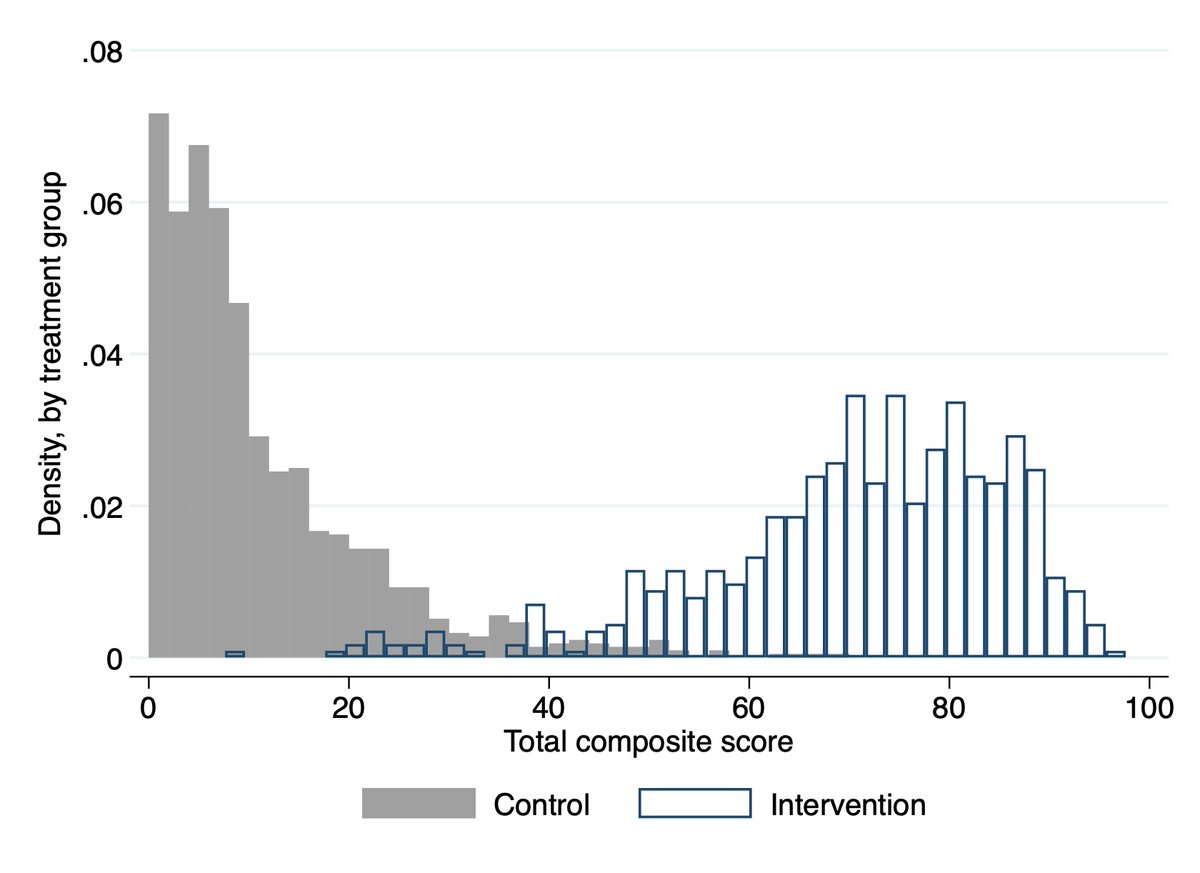

The headline result: we found tremendous gains in learning.

In the commonly used SD metric, this was 3.2 SD, but the SD is hard to use in this context because counterfactual learning is so low

Here are the test score distributions for intervention and control kids

14/n

In the commonly used SD metric, this was 3.2 SD, but the SD is hard to use in this context because counterfactual learning is so low

Here are the test score distributions for intervention and control kids

14/n

Broken down across the skills we measured – such as reading words, understanding short passages, doing two-digit subtraction, and solving word problems

we saw massive gains across the board

(the figure on the left is for math skills; the one on the left is for reading)

15/n

we saw massive gains across the board

(the figure on the left is for math skills; the one on the left is for reading)

15/n

The second study has a (mercifully) shorter title: “Large learning gains in pockets of extreme poverty: Experimental evidence from Guinea Bissau”

sciencedirect.com/science/articl…

It took place in rural parts of Guinea Bissau, another low-income West African country

16/n

sciencedirect.com/science/articl…

It took place in rural parts of Guinea Bissau, another low-income West African country

16/n

Guinea Bissau is in worse shape than Gambia

Since independence (1974) it has had several coups and much other strife; until 2018, no president had finished a full term

Outside of the capital there is no power grid, and the reach of other public services is similarly low

17/n

Since independence (1974) it has had several coups and much other strife; until 2018, no president had finished a full term

Outside of the capital there is no power grid, and the reach of other public services is similarly low

17/n

This, of course, includes education.

As a result, learning levels there are also extremely low.

A national study of education in the country that some of us ran (nber.org/papers/w18971) found even lower literacy than in the Gambia: 24% for males, < 3% for females

18/n

As a result, learning levels there are also extremely low.

A national study of education in the country that some of us ran (nber.org/papers/w18971) found even lower literacy than in the Gambia: 24% for males, < 3% for females

18/n

Because service provision is so low, we studied schools run in lieu of the government, instead of after school remedial lessons as in Gambia

We hoped to also study a para teacher model, similar to that studied in the Gambia paper

Unfortunately, we ran into some trouble...

19/n

We hoped to also study a para teacher model, similar to that studied in the Gambia paper

Unfortunately, we ran into some trouble...

19/n

You can find details on what happened in the paper and its appendix, copied in the images below

The short story: we hired para teachers, trained them, and then they quit

Starting over, we changed the model, hiring trained teachers to live and teach in study villages

20/n

The short story: we hired para teachers, trained them, and then they quit

Starting over, we changed the model, hiring trained teachers to live and teach in study villages

20/n

Otherwise, the intervention was similar, using scripted lessons, extensive monitoring, and providing adequate resources to support operations

It began with a year of pre-primary to get kids up to speed with Portuguese, then three academic years of skill-focused learning

21/n

It began with a year of pre-primary to get kids up to speed with Portuguese, then three academic years of skill-focused learning

21/n

Here, we found tremendous results:

after four years of intervention, 60 percent of kids in treatment villages could read fluently, with comprehension

compared to 0.1% in the control group!

(overall distributions again shown below)

22/n

after four years of intervention, 60 percent of kids in treatment villages could read fluently, with comprehension

compared to 0.1% in the control group!

(overall distributions again shown below)

22/n

Together, our studies show two main things:

One, in the absence of external intervention, the vast majority of people in these places will grow up illiterate and innumerate

Two, if we want to, WE CAN CHANGE THIS!!!

(we are really excited about that second message)

23/n

One, in the absence of external intervention, the vast majority of people in these places will grow up illiterate and innumerate

Two, if we want to, WE CAN CHANGE THIS!!!

(we are really excited about that second message)

23/n

The “trick” is that it’s not cheap

The para-teacher intervention in the Gambia cost $242 per kid year

The intervention in Guinea Bissau cost $425 per kid per year

While both interventions are highly cost-efficient, they are well beyond the means of local government

24/n

The para-teacher intervention in the Gambia cost $242 per kid year

The intervention in Guinea Bissau cost $425 per kid per year

While both interventions are highly cost-efficient, they are well beyond the means of local government

24/n

Big picture take-aways:

It is hard to fix the problem of low learning in extremely poor, remote parts of the developing world.

But it is possible. And it is very, very important.

25/n

It is hard to fix the problem of low learning in extremely poor, remote parts of the developing world.

But it is possible. And it is very, very important.

25/n

Why is it important?

These places are at the far left tail of the distribution of both income and learning

Helping them must be a big part of global efforts to fight inequality, promote #Globaljustice #GlobalDevelopment, reach #sdg4 (we see you, #EdTwitter #EduTwitter)

26/n

These places are at the far left tail of the distribution of both income and learning

Helping them must be a big part of global efforts to fight inequality, promote #Globaljustice #GlobalDevelopment, reach #sdg4 (we see you, #EdTwitter #EduTwitter)

26/n

Also, because literacy and numeracy can be transformative for health, economic and political activity, and a host of other downstream outcomes

This has major implications for the life, death, and flourishing of millions of people in these places

27/n

This has major implications for the life, death, and flourishing of millions of people in these places

27/n

There are many other reasons, but this thread is already rather long – if you’re looking for more, please read the papers:

Gambia: sciencedirect.com/science/articl…

...

28/n

Gambia: sciencedirect.com/science/articl…

...

28/n

and Guinea Bissau: sciencedirect.com/science/articl…

And, of course, email me / us with questions. The “we” are the coauthors and other contributions mentioned in each.

29/n

And, of course, email me / us with questions. The “we” are the coauthors and other contributions mentioned in each.

29/n

We are immensely grateful to a group too long to mention here (see the paper acknowledgements!). I (Alex) want to express my gratitude to my communities, friends and family in Gambia, Bissau, London, Indiana, New York @TeachersCollege @EPSAatTC @Columbia_CDEP @ColumbiaCPRC

30/n

30/n

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh