It’s become common to see an academic dropping off Twitter to escape abuse.

It starts with a tweet or media appearance commenting on evidence from their field of study. Someone takes exception to their message, outrage spreads. Their timeline becomes a torrent of hostility.

It starts with a tweet or media appearance commenting on evidence from their field of study. Someone takes exception to their message, outrage spreads. Their timeline becomes a torrent of hostility.

This is hardly unique to researchers. Twitter is a bear pit.

Public engagement is part of the academic job. Funders expect it. A #publichealth crisis demands it. Yet we have calls for Covid scientists to #resign. One expert’s bio says simply: I block.

How did it come to this?

Public engagement is part of the academic job. Funders expect it. A #publichealth crisis demands it. Yet we have calls for Covid scientists to #resign. One expert’s bio says simply: I block.

How did it come to this?

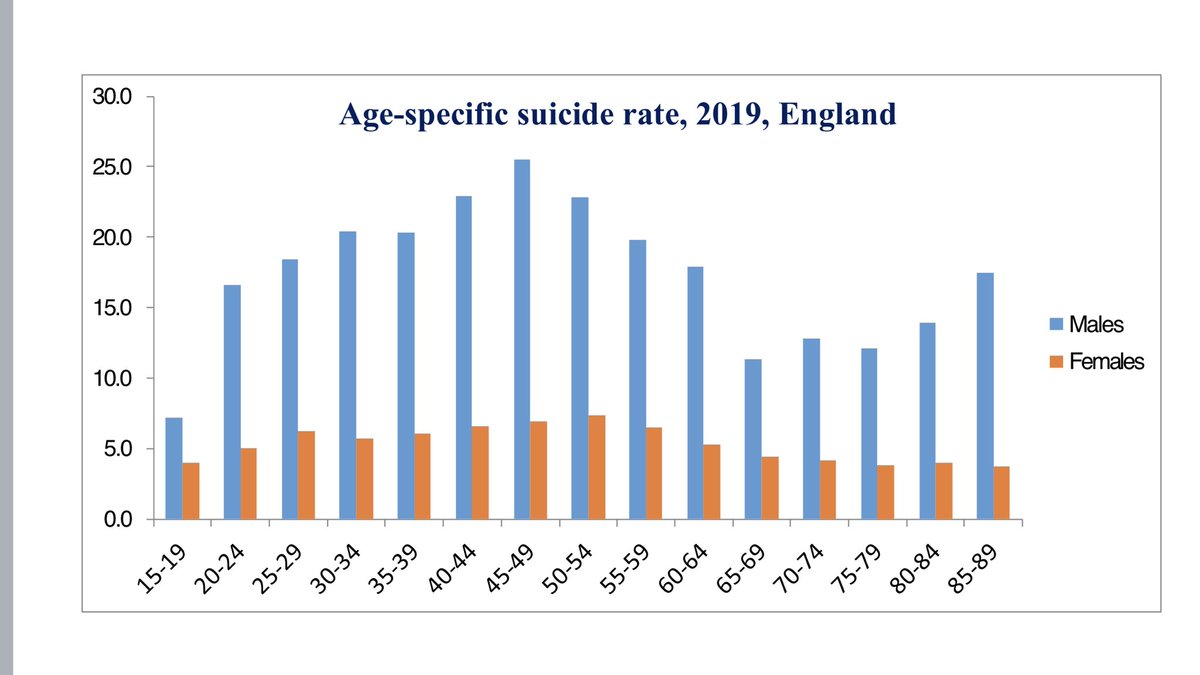

I should mention my own brush with the Twitter pile-on, though it was comparatively minor. In November my research group released the first pandemic suicide figs for England. Against expectations, we found no rise. The findings were later published here: thelancet.com/journals/lanep…

Over the next week I received hundreds of angry tweets: insults, abuse, a few implied threats. Colleagues emailed: what is going on?

Suicide had become a political issue in the pandemic. Claims of a huge rise were everywhere, blamed on lockdown. Our findings were inconvenient.

Suicide had become a political issue in the pandemic. Claims of a huge rise were everywhere, blamed on lockdown. Our findings were inconvenient.

https://twitter.com/bbcrealitycheck/status/1277654233093898240

Attacks came from Covid-deniers, libertarians, anti-vaxxers. We were wrong, they said, and what’s more, we knew we were wrong. We were up to something.

Some alleged flaws in the study. Note to academics: “This is explained in the paper” is the most pointless of comebacks.

Some alleged flaws in the study. Note to academics: “This is explained in the paper” is the most pointless of comebacks.

It’s tempting to shrug & move on. But to treat abuse lightly is to normalise it. And harassment of researchers on whose independence we rely in a crisis should never be normal.

And if researchers give up on public dialogue, the stage is clear for charlatans. We all lose.

And if researchers give up on public dialogue, the stage is clear for charlatans. We all lose.

Equally, seeing it simply as the product of ignorance - the pitchfork mob at midnight - is simplistic & will get us nowhere.

Public outrage at scientists is a social phenomenon powerful enough to have shaped the course of a pandemic. It needs to be understood.

Public outrage at scientists is a social phenomenon powerful enough to have shaped the course of a pandemic. It needs to be understood.

It starts from the dominant political force of our time, a sense of being excluded, a belief that decisions affecting us all are the preserve of people who know nothing of real lives.

Hostility to “the elite” isn’t new. It has been a tool of populist leaders for centuries.

Hostility to “the elite” isn’t new. It has been a tool of populist leaders for centuries.

Add to that something more recent, the cynical denigration of experts, a word that now carries a pejorative sense: out of touch. Or worse: hiding the truth, in the pay of the powerful.

Twitter brings in a new element: an egalitarian format that creates equivalence, real or not.

I’m entitled to my opinion, say the keyboard warriors. And so they are.

My opinion is based on 30 yrs of study, says the expert.

Exactly what you’d expect from the elite.

I’m entitled to my opinion, say the keyboard warriors. And so they are.

My opinion is based on 30 yrs of study, says the expert.

Exactly what you’d expect from the elite.

Twitter also brings a level of aggression to every debate, stoked by anonymity, like road rage.

Resign, sack, arrest, imprison - these words reverberate across social media. No disagreement is too trivial to end with insults & accusations.

theguardian.com/science/2018/m…

Resign, sack, arrest, imprison - these words reverberate across social media. No disagreement is too trivial to end with insults & accusations.

theguardian.com/science/2018/m…

And Twitter runs on confirmation bias. People follow, like, retweet. Sure of what they believe. It’s unsettling if an expert says otherwise.

But aren’t experts in a bubble of their own? Do I know what the public believe on suicide? I look at who I follow, they are all like me.

But aren’t experts in a bubble of their own? Do I know what the public believe on suicide? I look at who I follow, they are all like me.

Underlying this is the cultural rise of subjective truth. People talk of “my truth” when they mean “my experience”. On Twitter, they may see a new treatment successfully trialled & say: it didn’t help me. And who can blame them for putting their experience first?

There was in fact another group who criticised our suicide data, without political motive. They were people whose mental health had suffered during the pandemic. They saw in our findings a denial of their experience.

In health research, subjective experience has gone from dismissal as “anecdote” to vital evidence, a crucial driver of “personalised” care. In my own field, the narratives of bereaved families, so tragic & compelling, are why #suicideprevention has gained its high public profile.

Individual experience sits alongside population data, enriching large-scale studies. They are not in opposition. Both are needed. Both come with uncertainty. Experience can vary. Data can change.

Uncertainty is the stuff of academic life. No research is perfect.

Uncertainty is the stuff of academic life. No research is perfect.

On Twitter, academic uncertainty meets subjective truth. We become defensive.

Can Twitter ever be mature enough to discuss uncertainty? To see the difference between belief, opinion & evidence? Between subjective experience & subjective truth?

Not yet.

Can Twitter ever be mature enough to discuss uncertainty? To see the difference between belief, opinion & evidence? Between subjective experience & subjective truth?

Not yet.

What can academics do to improve dialogue with the public on social media? Zero tolerance of abuse is essential. So too is engaging with the public on their terms, valuing their experience. Reassure them of our independence, esp from commercial funders. Explain uncertainty.

We must also convince the public that when we speak about a research field we have the expertise to do so, we are not using academic titles as a smokescreen for private opinion no more valuable than anyone else’s. We’ve seen this in the pandemic, it diminishes us all.

The public too have a responsibility to make this dialogue work. Challenging commonly held beliefs, their own & other people’s, is what academics do, it’s how knowledge advances, for public benefit. It should be encouraged, not cancelled.

And in an age when information is power, is it too much to expect that interpreting evidence should be something everyone can do, as important as numeracy or grammar? Sampling, small numbers, bias. Taught in school, skills for life.

Ends/

Ends/

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh