"You just let it sit there?," asks a Justice on a Court that has agreed to hear exactly *one* #GTMO appeal since ruling in 2008 that the federal courts must resolve these cases — and dismissed that case without deciding it? It's almost like they ... haven't been paying attention.

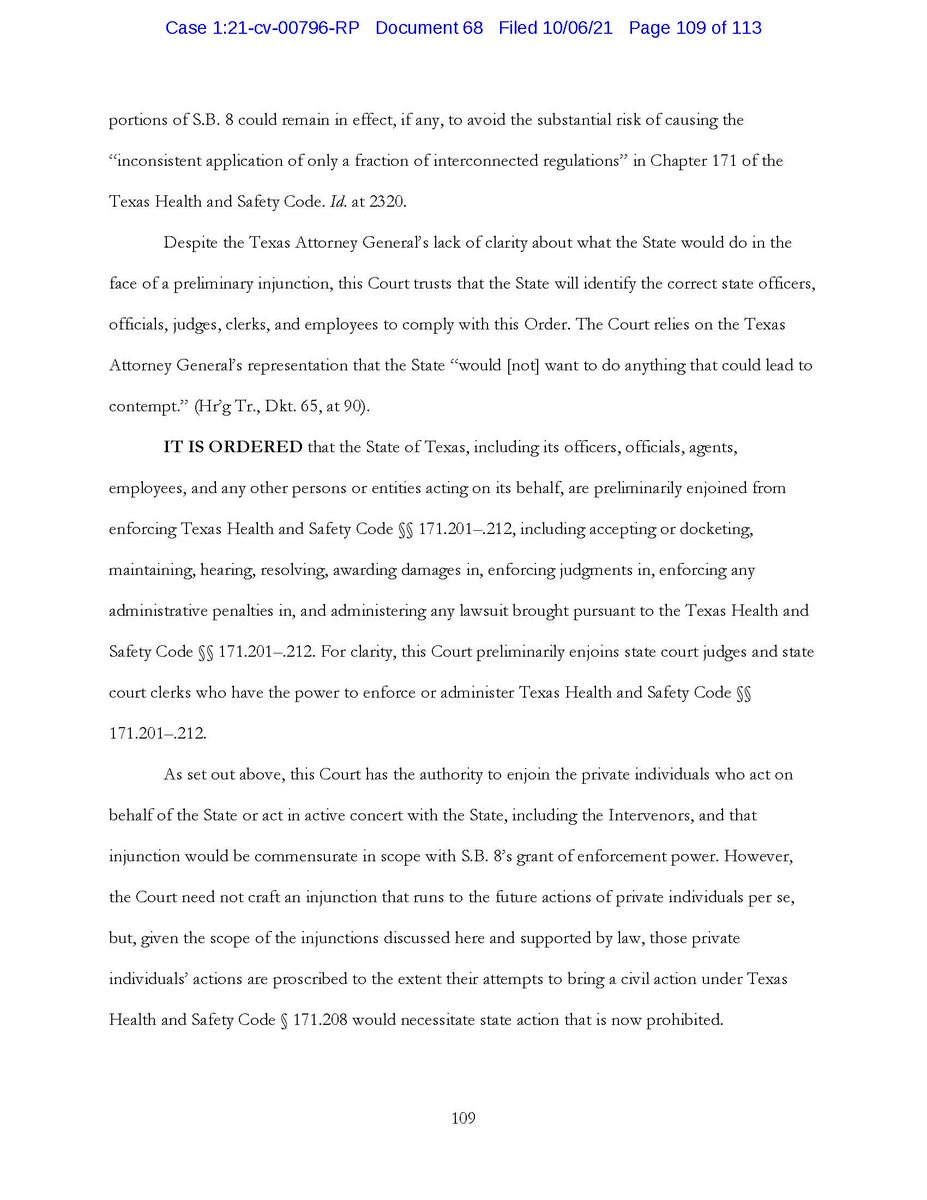

https://twitter.com/qjurecic/status/1445802646850392064

Here's an article from ... 2011 ... on the various procedural hurdles and roadblocks that the D.C. Circuit had already articulated to bog down the #GTMO detainee litigation:

scholarship.shu.edu/cgi/viewconten…

Suffice it to say, matters haven't improved much in the ensuing ... decade.

scholarship.shu.edu/cgi/viewconten…

Suffice it to say, matters haven't improved much in the ensuing ... decade.

In case you're wondering, the *one* #GTMO appeal that #SCOTUS agreed to take up since Boumediene was Kiyemba v. Obama — about whether those detainees who *won* their habeas petitions had a right to release *into* the United States.

Here's how that ended:

supremecourt.gov/opinions/10pdf…

Here's how that ended:

supremecourt.gov/opinions/10pdf…

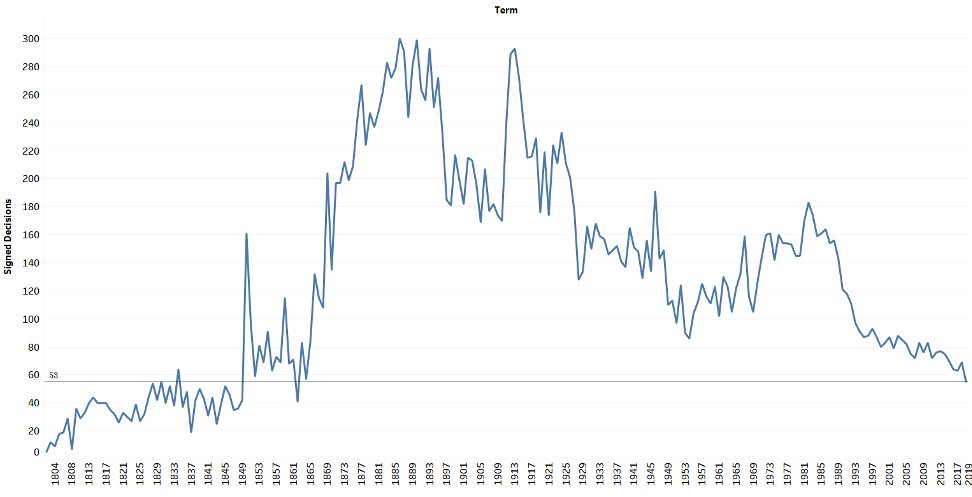

And the last time that any Justice publicly commented on #SCOTUS's *refusal* to take up an appeal in a #GTMO habeas case, it was <checks notes> Justice Breyer, in 2019:

https://twitter.com/steve_vladeck/status/1138077166078517249?s=20

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh