German China scholars have to find an answer to China's increasing censorship on German academia, @DavidJRMissal and I write in @ForeignPolicy. If scholars don't act, the state has to step in and help protect academic freedom /1 foreignpolicy.com/2021/10/28/ger…

The most recent example of Chinese censorship is a cancelled book tour at Confucius Institutes affiliated with German universities. Last week, at the behest of a Chinese general consul, 2 journalists were disinvited from giving talks at CIs about their biography of Xi Jinping /2

Similar attacks on academia are becoming increasingly frequent. In response to western sanctions, the CCP retaliated by imposing counter-sanctions against, inter alia, western scholars and think tanks /3

1336 scholars signed a solidarity statement. Among the signatories were eighty China experts at German universities. Many prominent German China scholars did not sign the solidarity statement, maybe because they don’t want to risk Beijing’s support for their research projects /4

The response from Berlin was inadequate: German Foreign Minister Maas summoned the Chinese ambassador, but there was no public reaction to the CCP's attack on European China experts from Chancellor Merkel. By staying silent, she doubled down on her CCP-friendly China policy /5

Three months after the incident, the German Ministry of Education and Research announced a new initiative aimed at strengthening independent China research. But it is not cracking down on continued CCP interference in German academia /6

One reason is Germany’s federal system, where only the 16 states have oversight over universities. Another is that universities are largely exempt from freedom of information laws, and are all too eager to veil Chinese money boosting their budgets /7

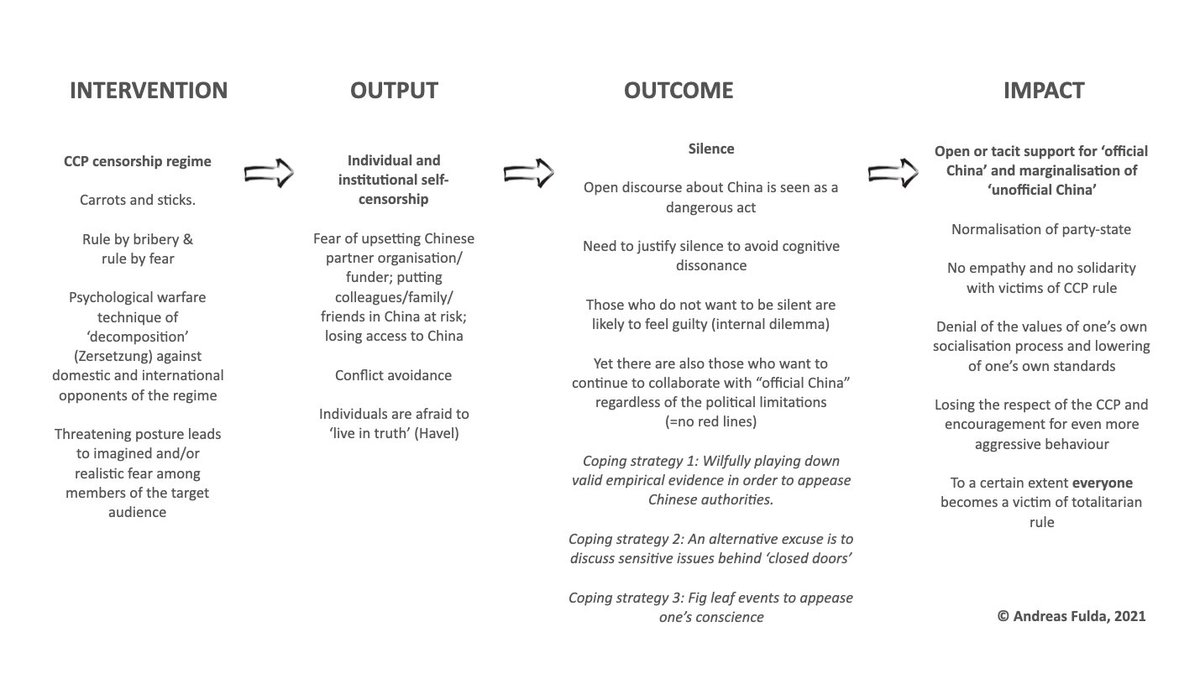

Individual researchers often have even more to lose should they be barred from entry to China, access to Chinese primary sources, and cooperation with their research partners. The CCP still has much leverage to influence academia, and its efforts continue to be successful /8

The German state seems unable to mitigate international risks to academic freedom: Neither the relevant government ministries nor the German political parties have developed a comprehensive China strategy for academia (with exception of the Greens and the Free Democrats) /9

Other key players have been just as ineffective. The German Rector's Conference has done little more than publish more than 100 “Leading questions about university cooperation with China" /10

Similarly, the German Academic Exchange Service defends cooperation with Beijing, and continues to downplay the risks. It is highly doubtful that waiting for those who run and benefit from continued cooperation to put a stop to foreign interference will be enough /11

Individual researchers and their academic associations will need to shoulder greater responsibilities: They could warn their universities about risks in cooperating with China and help scholars and institutions to develop policies dealing with censorship and self-censorship /12

Such intellectual leadership has been in short supply. E.g., in June 2021, the German Association for Asian Studies in a public statement bemoaned interference and self-censorship in German academia. But it failed to develop any proposals how to deal with such problems /13

The new German government might bring change: 2 of the 3 parties in the likely coalition are unusually critical of China. One key step would be the long-overdue establishment of a national security council to coordinate security issues, including defending academic freedom /14

There is also a strong need to train university administrators in political risk assessment, in hopes that they, too, will come to see the benefit of transparency and academic independence even at the cost of Chinese funding /15

Academic associations could help by making the case for disclosure of third-party funding. Transparency would empower professors and staff to critique unhealthy financial dependencies. Less reliance on funding from China could also help reduce self-censorship among scholars /16

If universities don't self-correct, tougher measures will be needed. In such a case the German government should consider legislative measures: /17

It could introduce a German version of the US Foreign Agents Registration Act and cut federal funding for universities which take Chinese money or fail in risk management. State governments should introduce effective transparency laws /18

German academics also need to critically reflect on their position toward the Chinese state. One start might be our 10 recommendations for a better China discourse /19

https://twitter.com/AMFChina/status/1450718434656980992?s=20

Staying silent on the CCP’s abuses at home and abroad is no longer a neutral position or count as disinterested research. We need a professional and public discourse about the best strategies to mitigate the CCP’s threats to academic freedom in Germany now /End

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh