Over the past twelve months @DavidJRMissal and I have jointly explored the issue of academic freedom and China. During our studies of the national context of Germany we noticed shortcomings both in terms of the academic and the public expert discourse about China /1

Our article "Mitigating threats to academic freedom in Germany: the role of the state, universities, learned societies and China" will soon be published in @InRights. In parallel we have developed ten suggestions aimed at improving the academic and public discourse about China /2

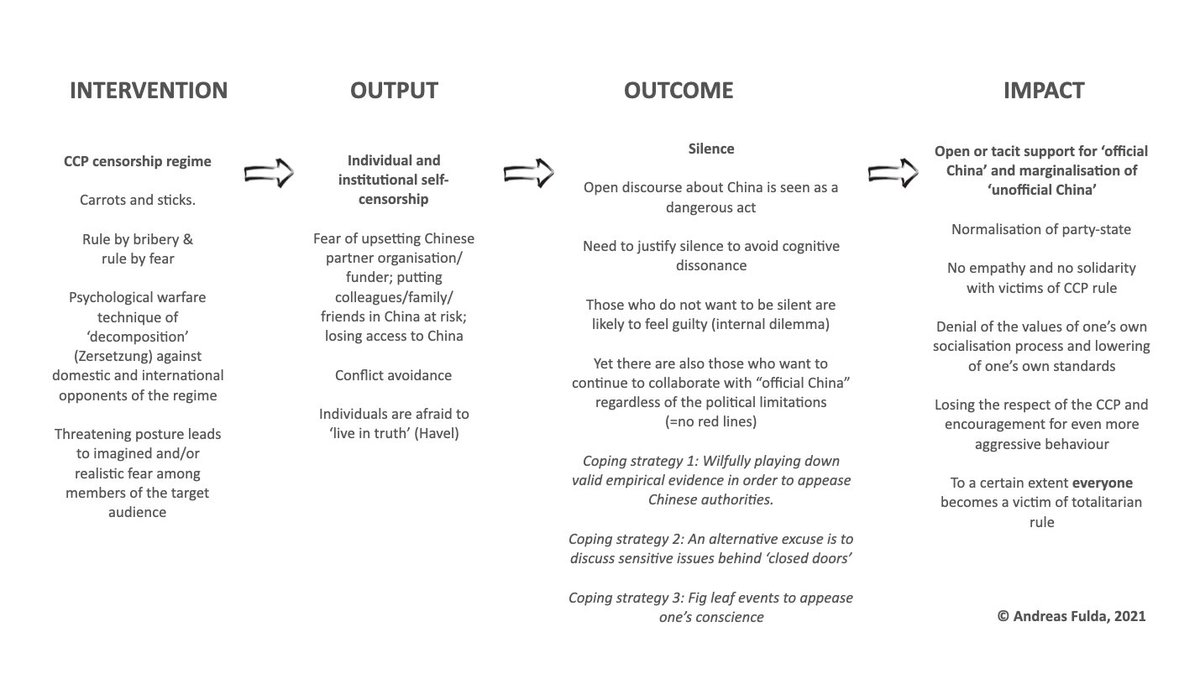

#1 Address the challenge of censorship and self-censorship.

China specialists should openly discuss the dangers of the Chinese Communist Party's (CCP) globalising political censorship regime and critically assess the challenge of individual and institutional self-censorship /3

China specialists should openly discuss the dangers of the Chinese Communist Party's (CCP) globalising political censorship regime and critically assess the challenge of individual and institutional self-censorship /3

Learned societies have a special responsibility to help develop sector-wide standards and protocols aimed at protecting academic freedom. They can lay the groundwork for reform by commissioning systematic studies about self-censorship at universities /4

Universities could consider adopting recommendations by Human Rights Watch from 2019 on how to mitigate risks to academic freedom in part or in full /5 hrw.org/news/2019/03/2…

#2 Research both 'official China' and 'unofficial China'.

China specialists need to be conscious that while the CCP under General Secretary Xi Jinping seeks a Gleichschaltung of Chinese academia, civil society and media under a unified narrative... /6

China specialists need to be conscious that while the CCP under General Secretary Xi Jinping seeks a Gleichschaltung of Chinese academia, civil society and media under a unified narrative... /6

... this remains a totalitarian ambition, not yet a fait accompli. Western China scholars should continue to research both what could be termed 'official China' (represented by the party-state) ... /7

... and 'unofficial China' (which includes independent-minded academics, doctors, entrepreneurs, citizen journalists, public interest lawyers and young students who no longer accept the CCP’s rule by fear) as well as the interactions between both /8

Despite an easier access to ‘official China’ for Western academia the viewpoints of representatives of 'unofficial China' should be represented equally in research on contemporary China /9

#3 Avoid stereotyping ‘China’ and ‘the West’.

China scholars should be mindful of the downsides of pitting 'China' vs 'the West'. While such shorthands are common in the public discourse on China, such binary opposites do not capture the reality of a diverse ‘China’ /10

China scholars should be mindful of the downsides of pitting 'China' vs 'the West'. While such shorthands are common in the public discourse on China, such binary opposites do not capture the reality of a diverse ‘China’ /10

This stereotyping often mirrors the CCP’s narrative of a people united behind the party not able or willing to live in a democratic system. It suppresses the desire of people to live under a democratic system in both ‘China’ and ‘the West’ /11

#4 Beware of the downsides of overspecialisation.

Greater attempts should be made to strike a better balance between a generalist and specialist approaches to the study of China. When researching a local phenomenon in China the wider picture should not be disregarded /12

Greater attempts should be made to strike a better balance between a generalist and specialist approaches to the study of China. When researching a local phenomenon in China the wider picture should not be disregarded /12

e.g. when researching smart cities in China it should be noted that whilst CCTV cameras can help solve local problems such as traffic congestion, they simultaneously augment the central party-state's ability to exercise social and political control through grid management /13

Greater efforts should be made to analyse China simultaneously from holistic and reductionist perspectives /14

#5 Close the theory-to-practice gap.

In order to narrow the theory to practice gap greater efforts should be made to incorporate the views of practitioners. There is a tendency to see contemporary China exclusively through the lens of political or academic discourses /15

In order to narrow the theory to practice gap greater efforts should be made to incorporate the views of practitioners. There is a tendency to see contemporary China exclusively through the lens of political or academic discourses /15

This comes at the expense of observing and analysing communities of practice. Capturing the perspective of practitioners will require greater willingness to experiment with knowledge co-production /16

#6 Celebrate viewpoint diversity.

Whereas in the past public commentary on current Chinese affairs was mostly limited to a select few experts with extensive China expertise, in the 21st century the number of China pundits has exponentially increased /17

Whereas in the past public commentary on current Chinese affairs was mostly limited to a select few experts with extensive China expertise, in the 21st century the number of China pundits has exponentially increased /17

This means that experts with vastly different academic training and practical China experiences are joining the public discourse about China. This development is also due to missing diversity in viewpoints within the ‘traditional’ community of university-based China scholars /18

Viewpoint diversity should be welcomed, no matter whether taking place within or outside the world of academia /19

#7 Live in truth.

To quote Einstein, experts "must not conceal any part of what one has recognised to be true" in the public discourse about China. 'Being economical with the truth' distorts the public discourse about China /20

To quote Einstein, experts "must not conceal any part of what one has recognised to be true" in the public discourse about China. 'Being economical with the truth' distorts the public discourse about China /20

For example, pundits should not consider public opinion polls conducted in authoritarian China as credible evidence for Chinese citizen support towards the CCP’s regime /21

Due to political censorship and self-censorship even seemingly scientific surveys should be taken with a big grain of salt. At best they reveal the efficacy of CCP propaganda /22

#8 Prevent conflicts of interests.

In order to enhance public trust in experts commenting on current Chinese affairs discourse participants should disclose any special interests /23

In order to enhance public trust in experts commenting on current Chinese affairs discourse participants should disclose any special interests /23

It is in their own interest for experts to create transparency about consultancy work and sources of supplementary income /24

Media outlets which interview experts or publish their op-eds should follow the good practice of @ConversationUK, which requires authors to provide a disclosure statement and answer questions about potential conflicts of interests or affiliations /25

#9 Show greater civil courage.

Junior experts should feel empowered to make their voice heard, even if their point of view run counter the conventional wisdom of senior politicians, bureaucrats, business leaders or other academics /26

Junior experts should feel empowered to make their voice heard, even if their point of view run counter the conventional wisdom of senior politicians, bureaucrats, business leaders or other academics /26

Both junior and senior experts should stand up for a more open discussion /27

#10 Exercise solidarity.

Experts who incur the wrath of the CCP for their critique of the party-state's authoritarian overreach deserve public solidarity and support (e.g., they should be invited to participate in projects, events, publications etc even more) /End

Experts who incur the wrath of the CCP for their critique of the party-state's authoritarian overreach deserve public solidarity and support (e.g., they should be invited to participate in projects, events, publications etc even more) /End

Compile @threader_app

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh