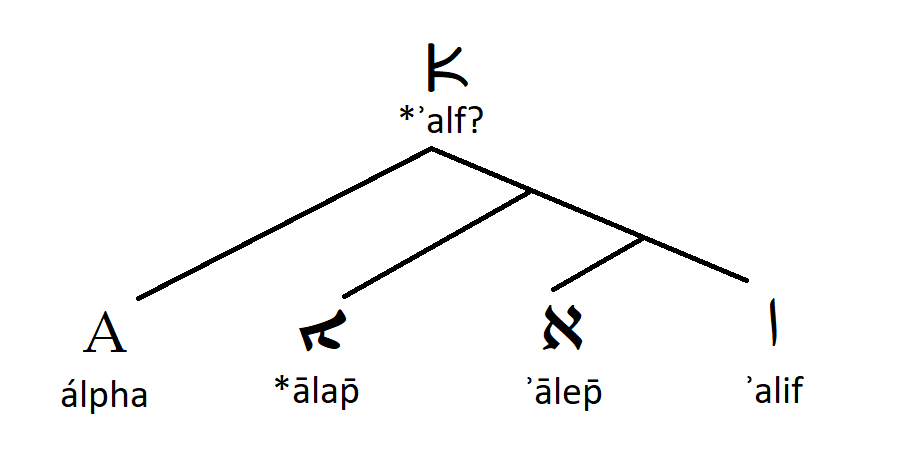

The #Deltacron tweet made a big impression on me yesterday and I've been thinking about letter names ever since. One thing to note is that we like to pretend we know what the #Phoenician letter names were, but we don't really. Most of the names you see are actually #Hebrew. 1/10

That goes for names like "aleph". Sometimes you'll see reconstructed forms, like "ʾalp", which are closer to the #Greek names and partially also attested in the Septuagint of Psalm 119 (118 in Gk)—but there they're actually Hebrew too, of course. 2/10 en.katabiblon.com/us/index.php?t…

One place where the Greek and Semitic letter names show weird correspondences is with the sibilants. @pd_myers has recently published on this (paywall): academic.oup.com/jss/article/64… 3/10

Myers follows Jeffery's (not the Arabist) explanation that because the Greeks only had one sibilant, they got confused and mixed the letters up; see table. The article uses square script instead of Phoenician but ז = 𐤆; ס = 𐤎; צ = 𐤑; ש = 𐤔. 4/10

But IMHO this doesn't adequately explain how /š/ became /ks/ and how /ts’/ became /sd/. Tropper notes that the reconstructed Proto-Semitic values for these sounds work out better:

𐤔 /s/ ➡ Σ /s/

𐤎 /ts/ ➡ Ξ /ks/

𐤆 /dz/ ➡ Ζ /sd/

𐤑 /ts’/ ➡ Ϻ /?/

5/10

jstor.org/stable/43380211

𐤔 /s/ ➡ Σ /s/

𐤎 /ts/ ➡ Ξ /ks/

𐤆 /dz/ ➡ Ζ /sd/

𐤑 /ts’/ ➡ Ϻ /?/

5/10

jstor.org/stable/43380211

But then why do the letters have the wrong name? If sígma was borrowed from šīn, why isn't it called sĩn or sĩ (like nũ from nūn), or even sínna? The name does look a lot more like sāmeḵ or #Syriac semkaṯ (*simk-a > *sikma > sígma). 6/10

One point I haven't seen made is that Ξ xi (oldest form of the Greek name: kseĩ) follows the pattern of the extra consonants that Greek didn't take from Phoenician: Φ phi (pheĩ), Χ chi (kheĩ), and Ψ psi (pseĩ). 7/10

So maybe we're dealing with a two-stage development here.

1. Greek borrows the alphabet. 𐤎 is still /ts/ so it is adapted to the next best thing in Greek, becoming Ξ /ks/.

THEN LATER:

8/10

1. Greek borrows the alphabet. 𐤎 is still /ts/ so it is adapted to the next best thing in Greek, becoming Ξ /ks/.

THEN LATER:

8/10

2. Greek borrows or re-borrows the letter names. At this point, /s/ in Semitic is written with 𐤎, a letter called something like *simk. So the Greek letter /s/, Σ, gets called sígma. At this point, Ξ /ks/ doesn't have a Semitic counterpart, so it becomes kseĩ by default. 9/10

These default letter names look a lot like what #Latin does with plosives (bē, cē, dē, pē, tē). Maybe this is what Greek did before borrowing the letter names too? No idea how we could tell.

That's it. More thoughts on letter names may follow later; you've been warned. 10/10

That's it. More thoughts on letter names may follow later; you've been warned. 10/10

ז = 𐤆

ס = 𐤎

צ = 𐤑

ש = 𐤔

ס = 𐤎

צ = 𐤑

ש = 𐤔

@threadreaderapp unroll @qumranqu

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh