Why do some people "backload" carbs?

What does this mean and what is the science behind it?

A 🧵 1/12

#exercise #carbs #lowcarb #lchf

What does this mean and what is the science behind it?

A 🧵 1/12

#exercise #carbs #lowcarb #lchf

"Carb backloading" is the practice of avoiding carbs early in the day and eating them later in the day, usually after some exercise.

Why would this make sense to do?

2/12

Why would this make sense to do?

2/12

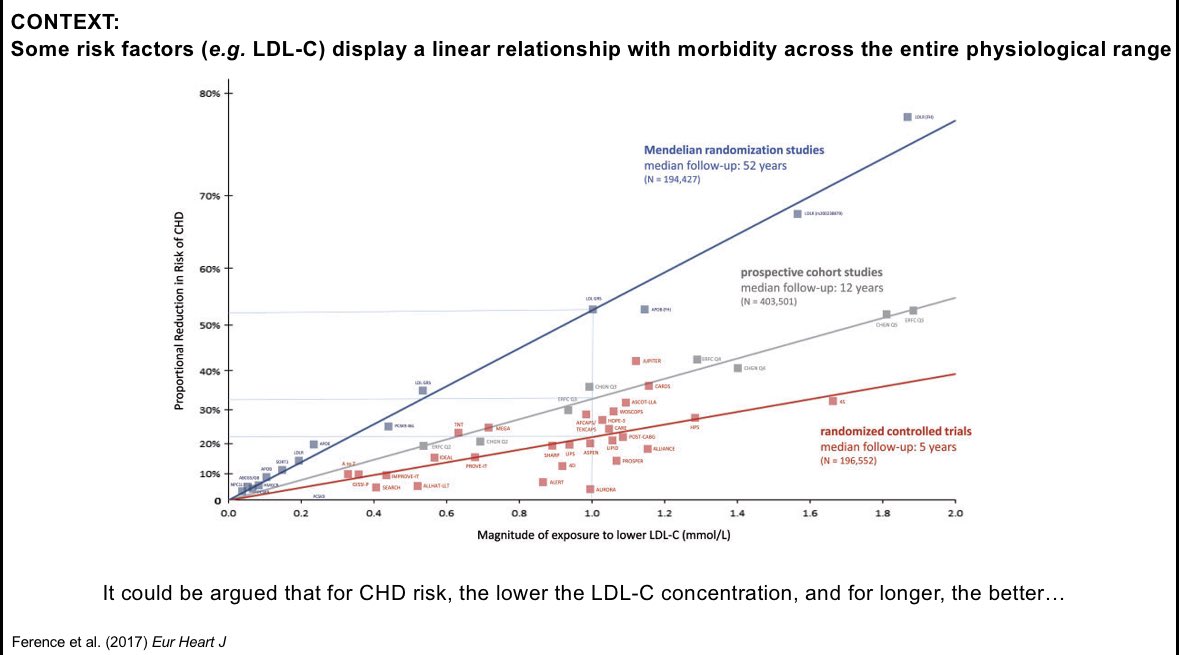

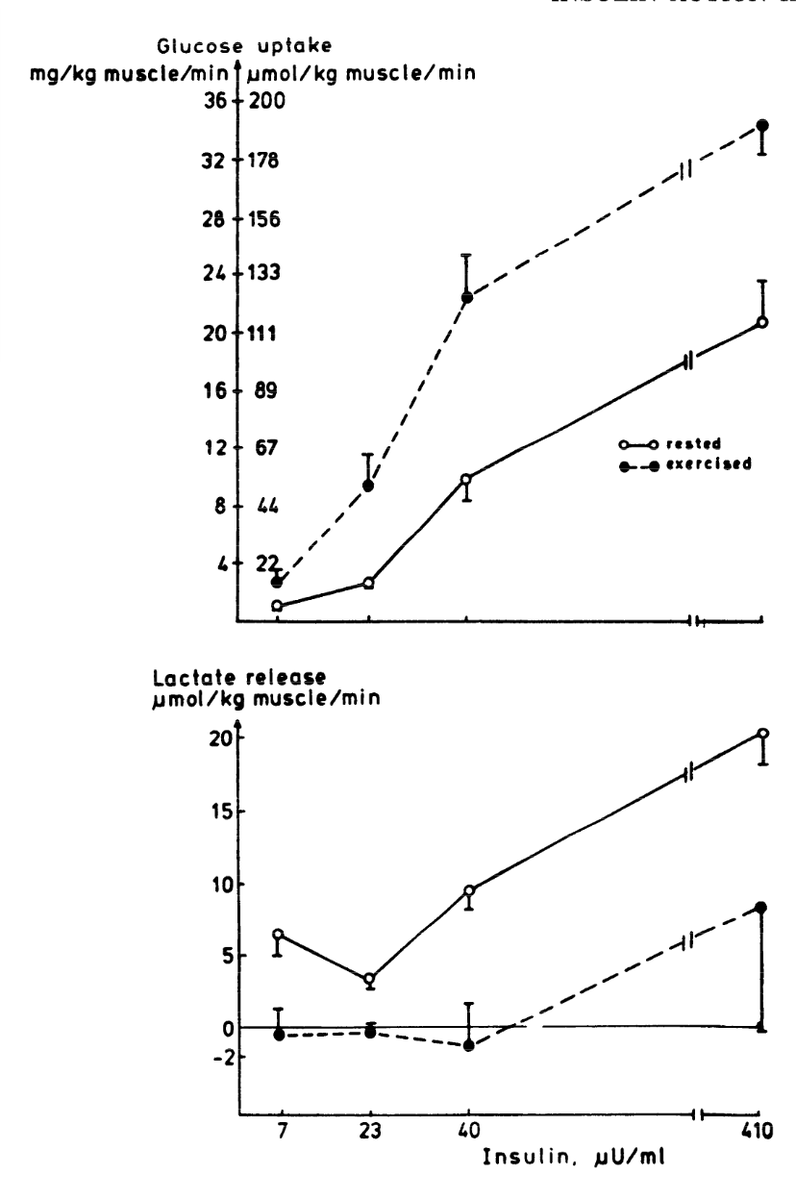

Some rationalise this based on evidence that after exercise, muscle glycogen levels are ⬇️ and muscle glucose uptake is ⬆️.

Ingested carbs can therefore restore glycogen.

⬆️ muscle glucose uptake should mean our blood glucose remains low right?

doi.org/10.1152/jappl.…

3/12

Ingested carbs can therefore restore glycogen.

⬆️ muscle glucose uptake should mean our blood glucose remains low right?

doi.org/10.1152/jappl.…

3/12

Not so fast...

Ingested carbs will contribute to glycogen.

But, ⬆️ muscle glucose uptake after exercise wont always keep blood glucose levels low.

Often, prior exercise can increase glucose in response to a meal (white bar in image = postexercise).

Whats going on here?

4/12

Ingested carbs will contribute to glycogen.

But, ⬆️ muscle glucose uptake after exercise wont always keep blood glucose levels low.

Often, prior exercise can increase glucose in response to a meal (white bar in image = postexercise).

Whats going on here?

4/12

Early work used a single-leg model of exercise to measure the effect of exercise on glucose uptake.

This is a very useful model but does have some downsides too.

The problem is that it doesn't capture what happens to the other (inactive) muscles.

doi.org/10.1152/jappl.…

5/12

This is a very useful model but does have some downsides too.

The problem is that it doesn't capture what happens to the other (inactive) muscles.

doi.org/10.1152/jappl.…

5/12

If we do cycling exercise with our legs, some of our inactive muscles (e.g. forearm) can actually be less insulin sensitive after exercise.

Possibly due to increased exposure to fatty acids without burning them.

doi.org/10.1152/ajpend…

6/12

Possibly due to increased exposure to fatty acids without burning them.

doi.org/10.1152/ajpend…

6/12

Another reason that prior exercise could increase blood glucose levels after a meal could be due to changes in the liver and/or the gut.

These will affect the rate of appearance of glucose into the blood and could counteract increased disappearance rates.

7/12

These will affect the rate of appearance of glucose into the blood and could counteract increased disappearance rates.

7/12

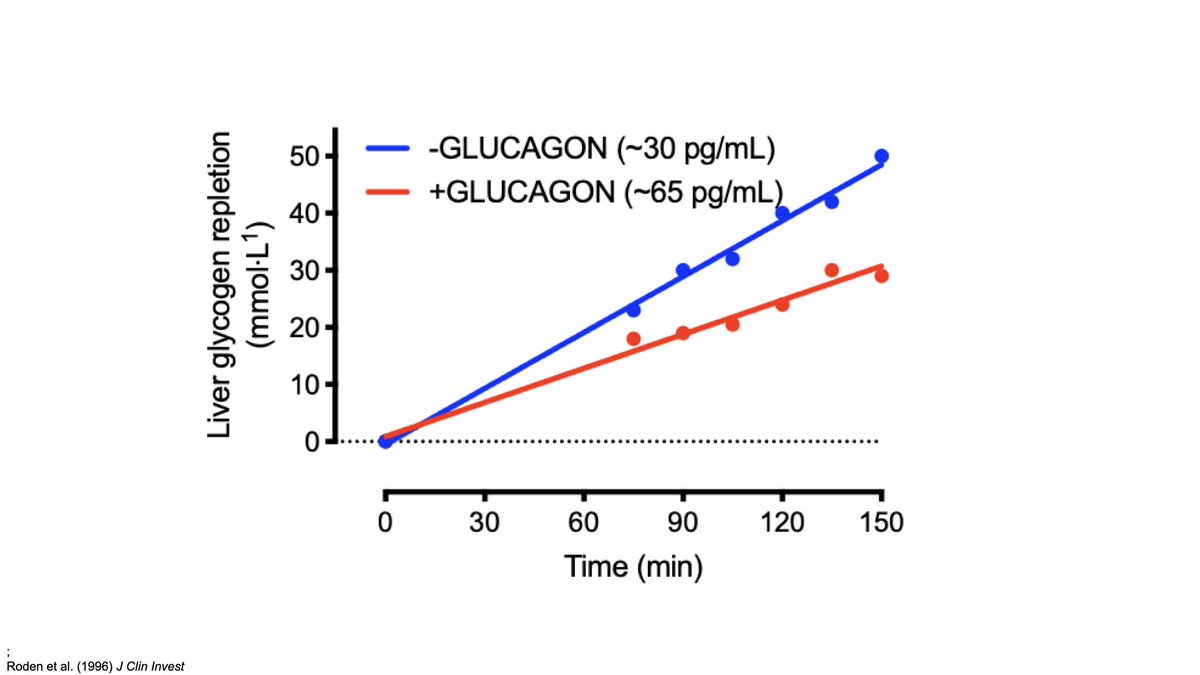

Whereas muscle shows high glycogen storage rates immediately after exercise, the liver displays a different pattern.

Slow immediately after exercise but then speeding up later.

Why isn't the liver storing glycogen as effectively after exercise?

doi.org/10.1152/japplp…

8/12

Slow immediately after exercise but then speeding up later.

Why isn't the liver storing glycogen as effectively after exercise?

doi.org/10.1152/japplp…

8/12

It might be because after exercise, the hormone glucagon is increased, and this counteracts the effects of insulin on liver glycogen storage (but doesn't affect muscle glycogen).

9/12

9/12

What about the gut?

In this study by @DrAJRose prior exercise ⬆️ the rate of blood glucose appearance from both the liver (B) and the gut (C).

Why this happens is still unclear. What are the implications?

Is exercise bad for our glucose control?

doi.org/10.1152/ajpend…

10/12

In this study by @DrAJRose prior exercise ⬆️ the rate of blood glucose appearance from both the liver (B) and the gut (C).

Why this happens is still unclear. What are the implications?

Is exercise bad for our glucose control?

doi.org/10.1152/ajpend…

10/12

Luckily, in people with type 2 diabetes, the increase in glucose appearance rate does not offset the increase in muscle glucose uptake after exercise.

In other words, this effect is interesting but unlikely to be relevant to people with diabetes.

doi.org/10.14814/phy2.…

11/12

In other words, this effect is interesting but unlikely to be relevant to people with diabetes.

doi.org/10.14814/phy2.…

11/12

This effect might explain why foods which normally can be classified as high and low glycaemic index (GI), can show very similar glucose responses in the first hour after exercise.

This one from @LouiseMBurke demonstrates this very clearly.

doi.org/10.1152/jappl.…

12/12

This one from @LouiseMBurke demonstrates this very clearly.

doi.org/10.1152/jappl.…

12/12

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh