Allow me to share some of the things I've learned.

Oct. 13. “Everyone very depressed. Men all seem to feel they will never see home again.”

Oct. 14. “All onboard very restless and unsettled not knowing what is ahead.”

One German prisoner looked like he was 15.

One Tommy had been wounded 12 times. “He said the Germans were dirty cowards and sometimes yelled like pigs

“Had another terrible one. So all they ended do[ing] was pack and bring him back without locating the trouble. During the early afternoon he talked a lot. Died at 4:30 p.m.”

March 12. “Such terrible wounds and ill men. May it never be my luck to see again.”

She also worried about her brother Alistair, who was at the front with the PPCLI.

Laurier died in March 1918 when the Germans shelled his battalion's positions.

His ship was carrying troops to Africa and was under order not to stop and sailed by the floating bodies.

llandoverycastle.ca

“Many more gaps in the wire were required that had been cut. In spite of the losses the survivors steadily advanced until close to the enemies’ wire by which time very few remained.”

The next morning, out of a total of 801 soldiers who went to battle, only 68 men had returned for roll call.

therooms.ca/sites/default/…

veterans.gc.ca/eng/remembranc…

For the Newfoundland Regiment, therooms.ca/thegreatwar/in…

The Canadian Great War Project website is also an invaluable resource

canadiangreatwarproject.com/general/about.…

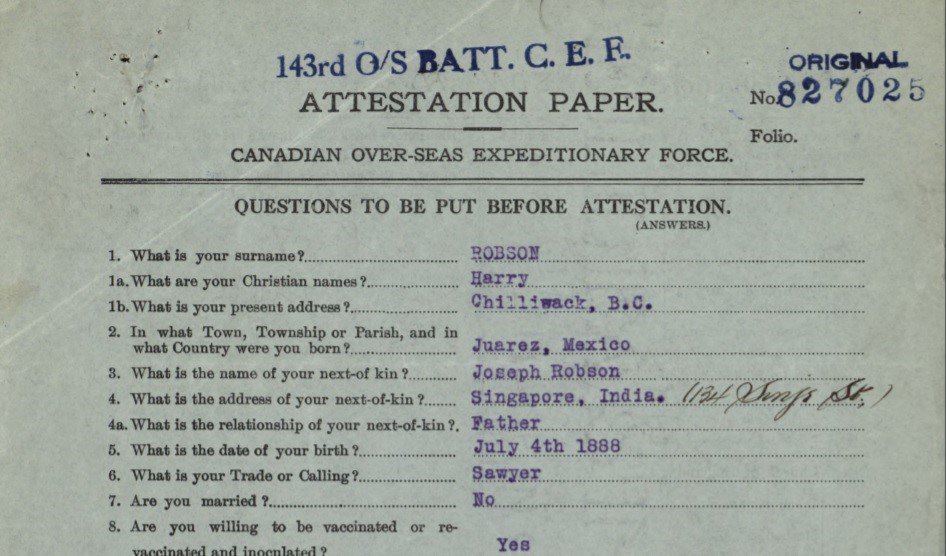

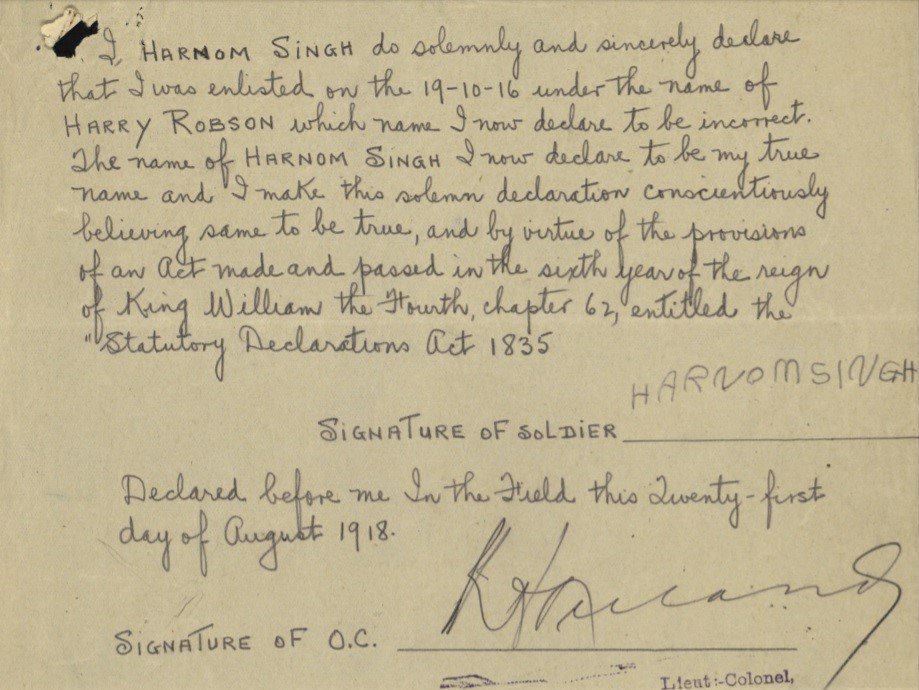

central.bac-lac.gc.ca/.item/?op=pdf&…

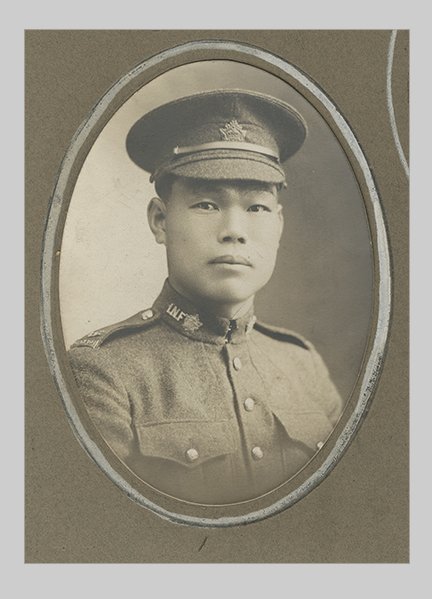

(photo from Nikkei National Museum)

central.bac-lac.gc.ca/.item/?op=pdf&…

Vincent left school early to find work. One of his sons, Gary, told me he remembers growing up poor and living in subsidized housing.

theglobeandmail.com/canada/article…