I have spent the past day weighing whether to like article because it is a fantastically executed example of #scicomm or dislike it because it is propaganda that distorts the evidence.

english.elpais.com/society/2020-1… via @elpaisinenglish

english.elpais.com/society/2020-1… via @elpaisinenglish

What makes it so effective is the #dataviz, the relatable examples, and the plainspeak. I read the translated English version, and it really is wonderful to read. I came away thinking that aerosol transmission was so clear and plainly obvious. Until I realized this is propaganda.

It quotes a letter as an "article in the prestigious @ScienceMagazine" [finding] that there is 'overwhelming evidence' that airborne transmission 'is a major route'" for transmission. This is misleading.

Although it acknowledges that its simulations are just that, simulation, the reader (and many twitterati) have suggested that it is truth. I will take 1 example to show how the article misleads.

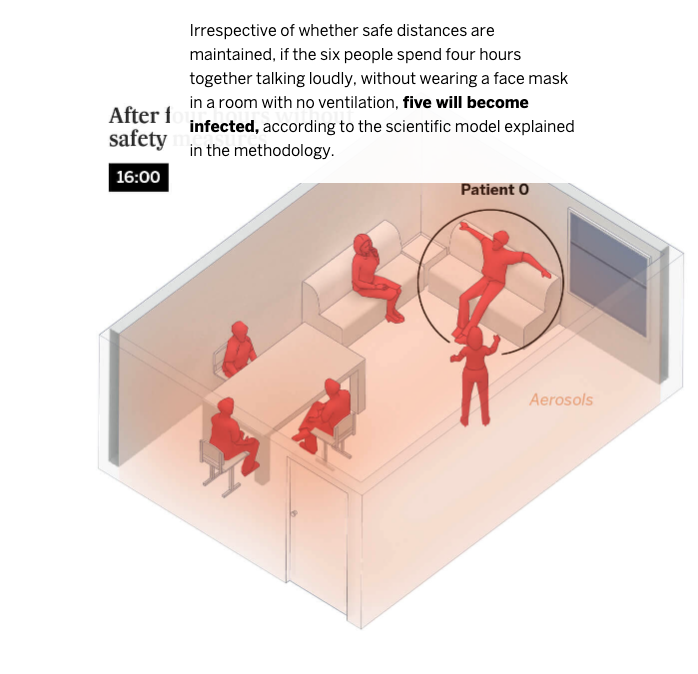

Here, they give an example of 6 people getting together in a home, and place the scenario & consequences as follows. From this, one would conclude (whether the authors are implying this or not), that household transmission should approach 83%—surely cohabitants are similar.

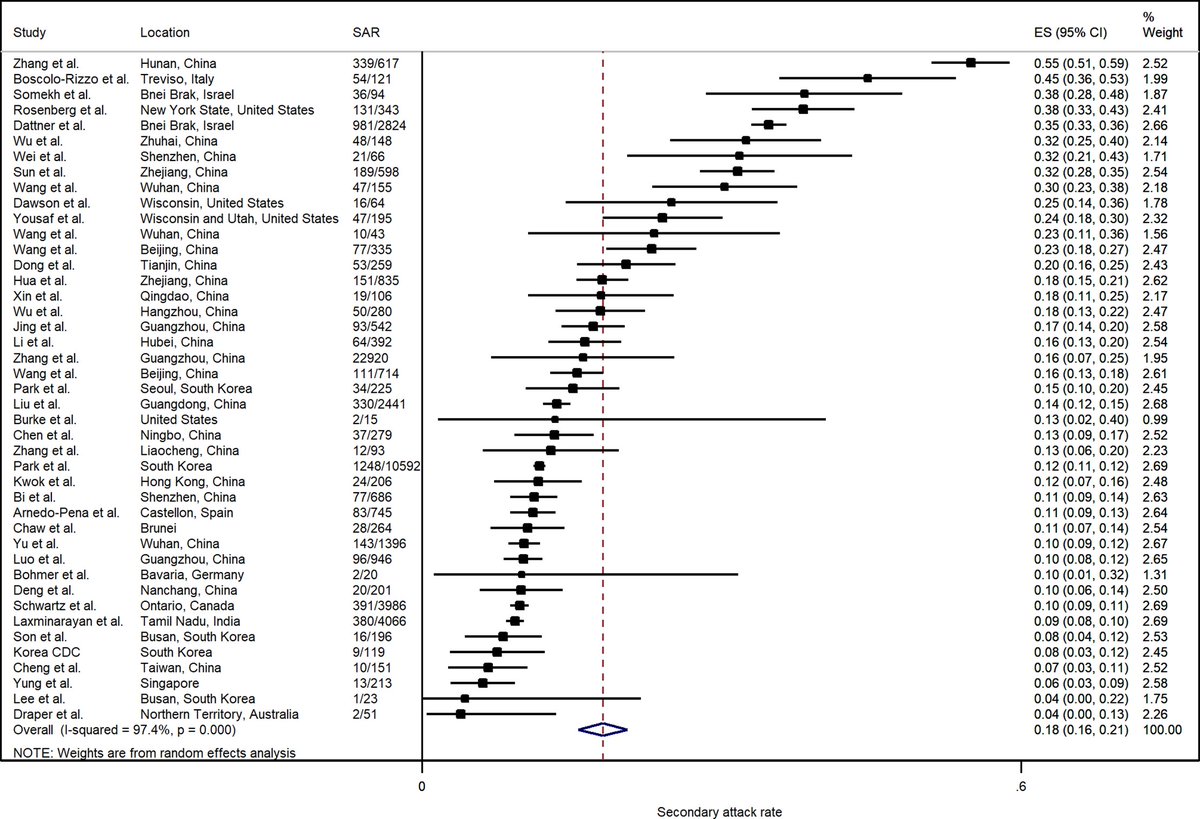

This is data from one of several meta-analyses looking at secondary household attack rate (SAR). What does it find?

Household SAR ranges from 3.9-30%.

Household SAR ranges from 3.9-30%.

Therein lies the problem: those arguing about the inarguable presence of aerosol transmission are ignoring (or avoiding) the inarguable evidence that it just ain't nearly as important as proximal spread.

Personally, I find this all tiresome. I think ventilation is important and avoiding indoor, crowded, unmasked exposure. But proximal unmasked exposure remains the primary means of transmission supported by the evidence.

It reminds me of this paper osf.io/k2d84/

It reminds me of this paper osf.io/k2d84/

I wish this article could be rewritten, acknowledging the epidemiological evidence we have and the uncertainty. Heck, I'd even be willing to co-author it! In meantime, caveat emptor.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh