While not there in the flesh, #sblaar20 and #iqsa2020 got me in a comparative mood between Hebrew and Arabic. I was reading some Zamaḫšarī's mufaṣṣal today and noticed an interesting comment on hollow root active participles, which may provide a link with Hebrew.

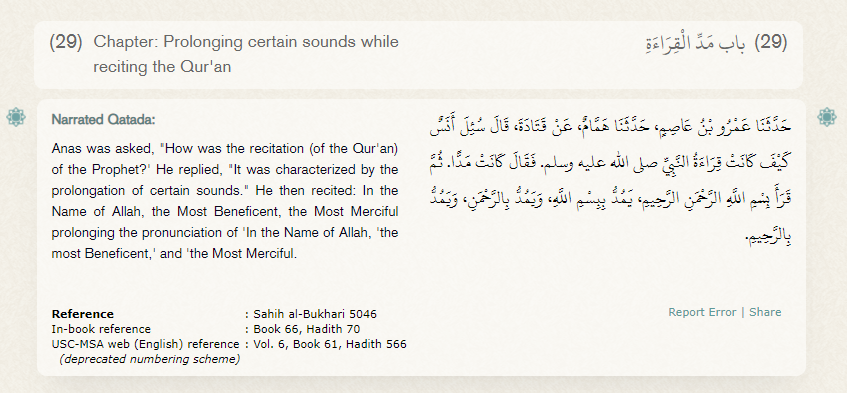

"As for the weakness in the active participle of those like qāla 'to say' and bāʿa 'to sell', the second root consonant is to be replaced with a hamzah, as in your speech qāʾilun 'saying', bāʾiʿun 'selling', and sometimes it is removed like your speech: šākun 'thorny'"

So while the normal pattern of such hollow roots active participles CāʾiC, there is at least one exceptional case where we find a pattern CāC. This caught my attention, because Hebrew has an unusual active participle for hollow roots that looks very similar to this.

Normal active participles have the pattern CoCeC < *CāCiC, just like Arabic, e.g. yošeḇ 'sitting' of the verb yåšaḇ. But hollow verbs surprisingly do not follow this pattern but instead have a vowel CåC. Which @bnuyaminim argues comes from *CawaC, e.g. qåm 'standing up' <*qawam

As a historical linguist, when you see such asymmetries which are difficult to explain synchronically this starts ringing alarm bells. It's an indication that the form may be old (principle of archaic heterogeneity).

While it is irregular in Arabic, šāk- 'thorny' gives us an indication that indeed the Hebrew pattern is old, and while regularized in most forms, is still retained in some works lie šāk-.

While grammarians conceive of this as the outcome of *šāwik > šā(wi)k, šāk is also the regular outcome of a historical *šawak-, which matches perfectly the reconstructed form of the Hebrew active participles of Hollow roots like qåm < *qawam.

This is a pretty strong indication that Hebrew's weird treatment is indeed not an unusual Hebrew-internal innovation, but rather a retention of an ancient asymmetrical system!

See also Benjamin's paper

academia.edu/31406146/The_H…

See also Benjamin's paper

academia.edu/31406146/The_H…

If you enjoyed this thread and want me to do more of it, please consider buying me a coffee.

ko-fi.com/phdnix.

If you want to support me in a more integral way, you can become a patron on Patreon!

patreon.com/PhDniX

ko-fi.com/phdnix.

If you want to support me in a more integral way, you can become a patron on Patreon!

patreon.com/PhDniX

Of course, as I post this tweet, I realize that Nöldeke noticed this 110 centuries ago. Not just in Quranic studies are we perpetually reinventing the wheel of what Nöldeke already discovered a century ago, also in Semitic studies.

See pages 207-216.

menadoc.bibliothek.uni-halle.de/ssg/content/ti…

See pages 207-216.

menadoc.bibliothek.uni-halle.de/ssg/content/ti…

Many more examples of CāC active participles listed in this chapter as well.

But at least the reason why šåḇ has an å instead of o no longer remains unclear thanks to @bnuyaminim. So that's progress!

But at least the reason why šåḇ has an å instead of o no longer remains unclear thanks to @bnuyaminim. So that's progress!

@threadreaderapp unroll

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh