There are verses in the Quran that are interesting because they form doublets: two verses that are almost verbatim identical in their contents.

There is a triplet like this Q7:141, Q14:6 (and a little different Q2:49) present an interesting text critical conundrum.

There is a triplet like this Q7:141, Q14:6 (and a little different Q2:49) present an interesting text critical conundrum.

The most elaborate version is the one in Q14:6

"And (remember) when Moses said to his people: "Remember the grace of god upon you when he delivered you from the people of Pharaoh who were imposing upon you horrible punishment, slaughtering your sons, and keeping your women alive

"And (remember) when Moses said to his people: "Remember the grace of god upon you when he delivered you from the people of Pharaoh who were imposing upon you horrible punishment, slaughtering your sons, and keeping your women alive

In that there is a great trial from your lord."

Both Q2:49 and Q7:141 get rid of the framing introduction.

Q2:49 uses a slightly different verse for "to deliver", naǧǧā instead of ʾanǧā -- two verbs of the same root with identical meaning.

Both Q2:49 and Q7:141 get rid of the framing introduction.

Q2:49 uses a slightly different verse for "to deliver", naǧǧā instead of ʾanǧā -- two verbs of the same root with identical meaning.

Q7:141 uses a different verb in the place of slaughtering, it reads يقتلون which is variously read as yuqattilūna "they were massacring you", while others read yaqtulūna "they were killing you". With the parallel verses, "they were massacring" seems more apt.

Another difference in this triplet is the conjugation for person of the verb "to deliver."

Q14:6 speaks of the delivery of God in the third person -- obviously triggered by the framing narrative.

Q2:49 is in the first person plural: God is speaking directly.

Q14:6 speaks of the delivery of God in the third person -- obviously triggered by the framing narrative.

Q2:49 is in the first person plural: God is speaking directly.

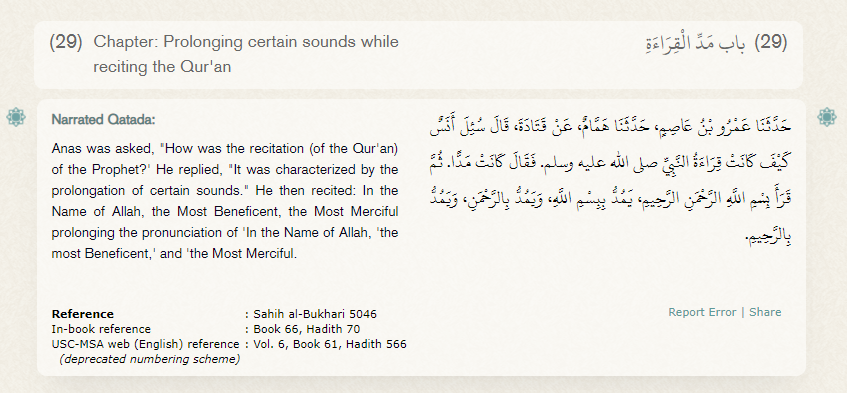

But with Q7:141 things get interesting: in the version we printed at the start of this thread, the person is clearly the first person plural as in Q2:49. But this is a famous place where the different regional Muṣḥafs disagree. The Syrian manuscript is in the third person!

This variant is reported by medieval rasm works to be a feature of the Syrian muṣḥafs. And indeed the Syrian canonical reciter Ibn ʿĀmir follows this rasm and reads ʾanǧā-kum "he delivered you".

Ancient manuscripts with Syrian variants indeed also have this variant:

Ancient manuscripts with Syrian variants indeed also have this variant:

So which version was the original, and which was copied from which? One question is how did this variant come about. There are two ways of understanding it I think. Either there this could be a scribal error, ʾanǧaynā-kum and ʾanǧākum are only one denticle apart.

It could be that a scribe forgot to write the second denticle, (or less likely wrote one too many). With it forgotten the once intended reading ʾanǧaynā-kum no longer works with the rasm, and the Syrian reader, bound to stick to the rasm, thus reads ʾanǧā-kum.

Alternatively, we could be dealing with an assimilation of parallels. The verse in Q14:6 has almost identical phrasing, and even uses the same ʾafʿala verb stem (unlike the Q2:49 version). Could the scribe have thought of the Q14:6 version and accidentally changed the person?

Either explanation seems possible, and in either case the Syrian version seems inferior. Cook, without explaining much, concluded that, among some of the other Syrian variants, this variant is "more or less wrong".

He doesn't explain why he considers it wrong, but...

He doesn't explain why he considers it wrong, but...

I think he probably decided this on contextual grounds. This version of the Moses story in Q7 entirely has God speak about himself in the first person plural. The third person version of the Syrian codex is an unusual break in this pattern, making it look rather out of place.

Thus if we assume that the text was corrupted in the copying process, (either through scribal error, or assimilation of parallels) it would seem that the Syrian variant was copied from the original first person plural form as found in the Medinan, Basran and Kufan codices.

If you enjoyed this thread and want me to do more of it, please consider buying me a coffee.

ko-fi.com/phdnix.

If you want to support me in a more integral way, you can become a patron on Patreon!

patreon.com/PhDniX

ko-fi.com/phdnix.

If you want to support me in a more integral way, you can become a patron on Patreon!

patreon.com/PhDniX

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh