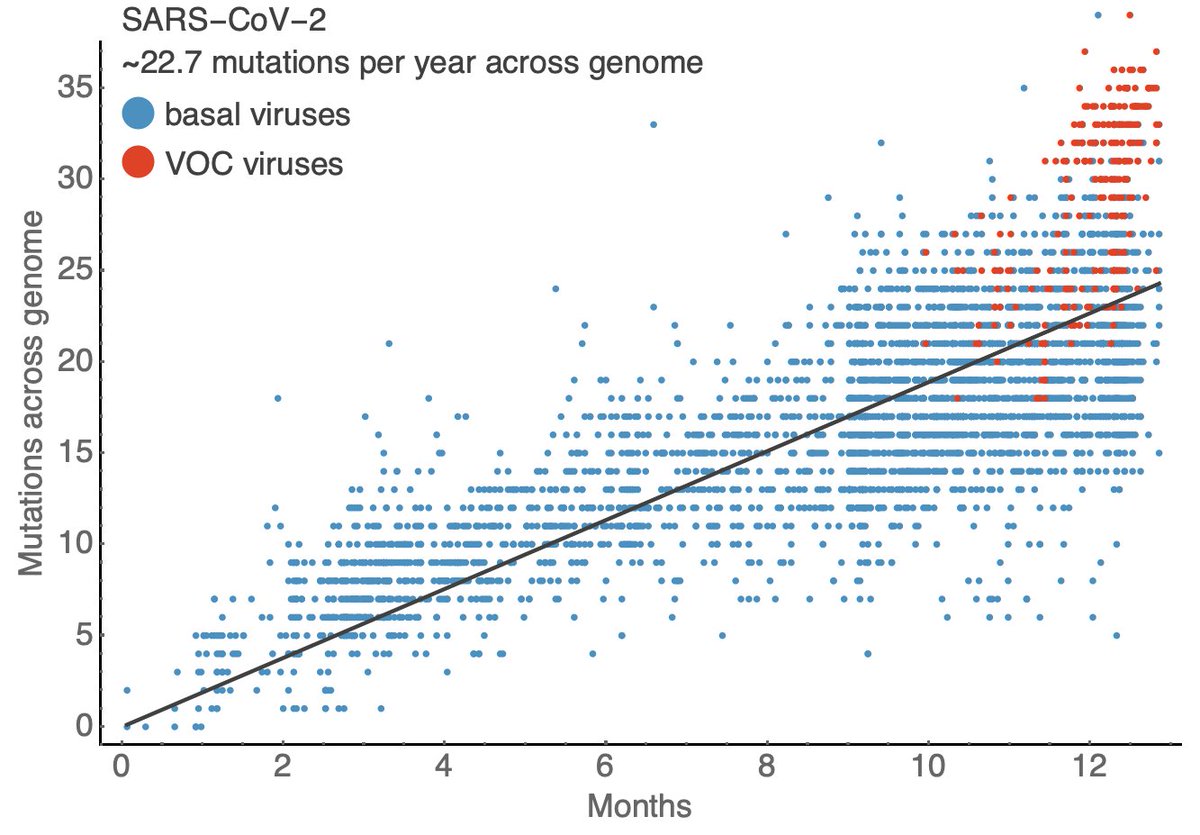

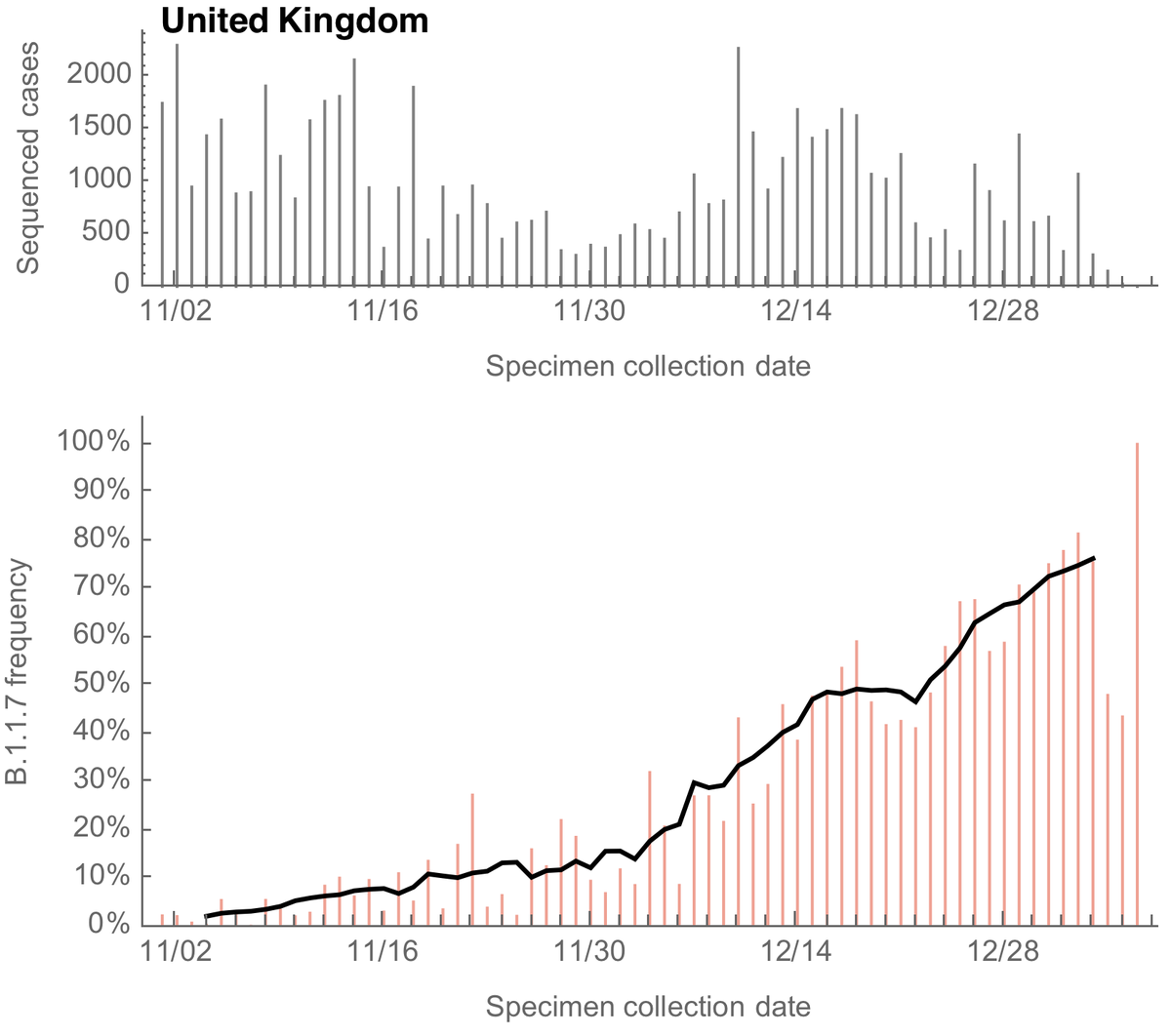

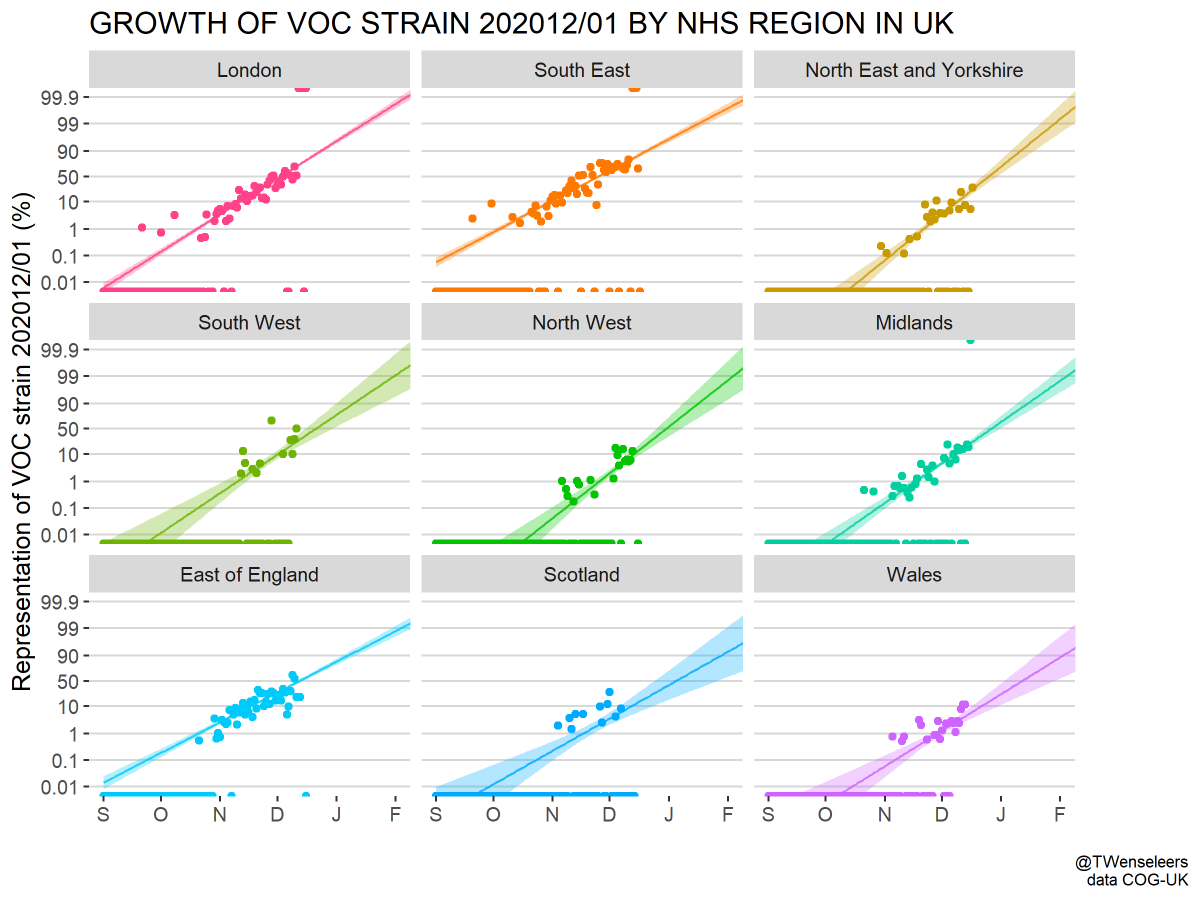

Since their recognition in the UK, South Africa and Brazil in Dec 2020 and Jan 2021, the variant of concern lineages B.1.1.7, B.1.351 and P.1 have continued to spread throughout the world with B.1.1.7 so far the most successful of the three. 1/15

https://twitter.com/trvrb/status/1349774271095062528

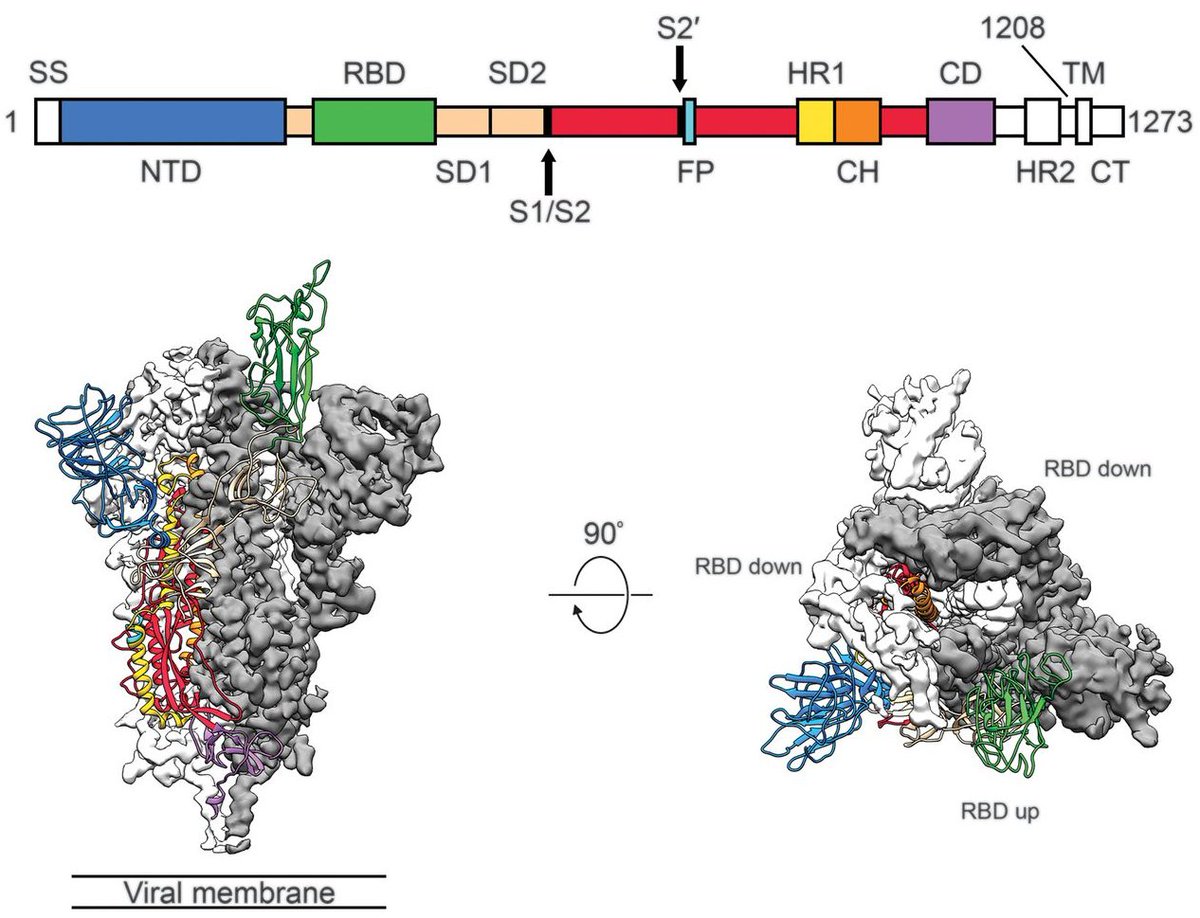

These lineages first received attention due to large numbers of mutations to the spike protein along with rapid increases in frequency in the UK, South Africa and Manaus, Brazil, but much subsequent attention has focused on key mutations E484K and N501Y. 2/15

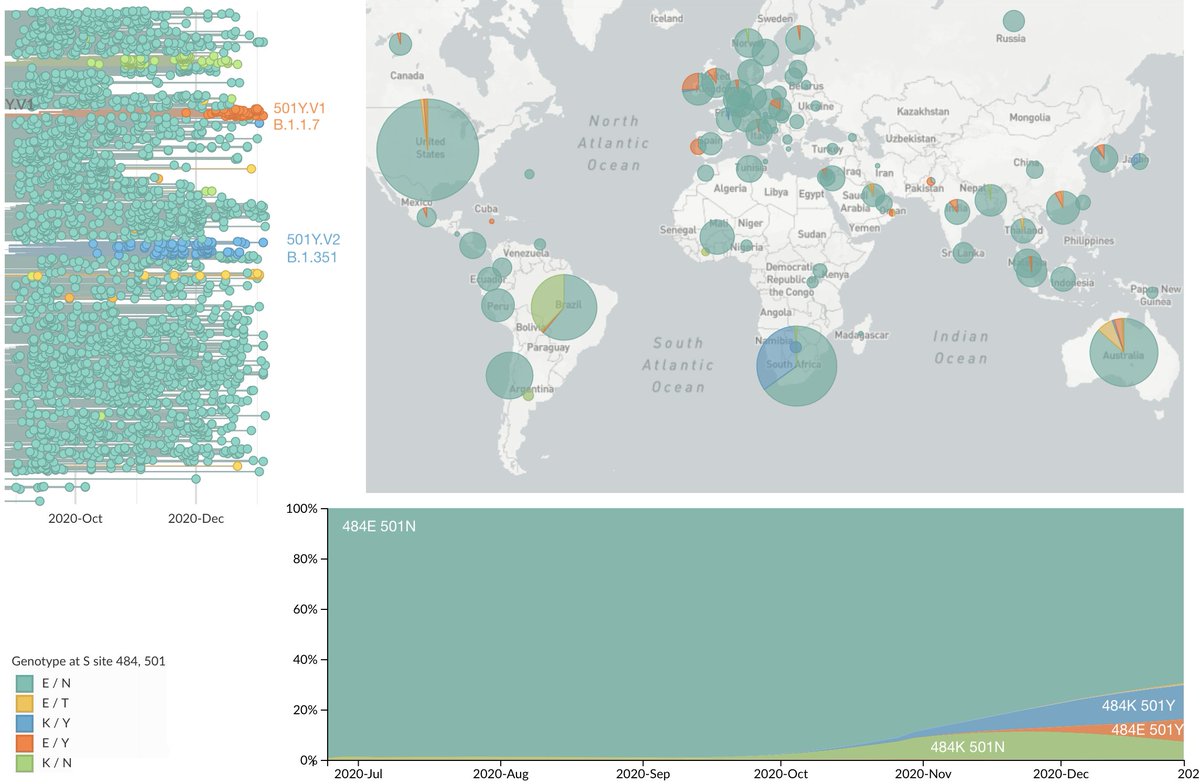

This figure shows genotype at sites 484 and 501 mapped onto a reference phylogeny of ~4k viruses sampled from all over the world with 484K viruses in light orange, 501Y viruses in blue (including B.1.1.7) and 484K+501Y viruses in dark orange (including B.1.351 and P.1). 3/15

It also shows frequency trajectory in this reference set alongside geographic distribution in the past 3 months, where viruses with 484K or 501Y now predominate in South America, Europe and Africa. An interactive version is available at nextstrain.org/ncov/global?c=…. 4/15

Although these VOC viruses are remarkable in their degree of evolution, their constituent mutations have appeared repeatedly in other circulating viruses. In addition to E484K and N501Y, mutation P681H has frequently emerged and spread on other genetic backgrounds. 5/15

Plots for mutations L18F and Q677H are shown here, but many other sites in spike protein show similar patterns of convergent evolution. 6/15

The point here is that it's not that B.1.1.7, B.1.351 and P.1 have unique mutations not present in other circulating viruses, it's that these VOC lineages have acquired some of the most extensive suites of spike S1 mutations seen in circulating viruses. 7/15

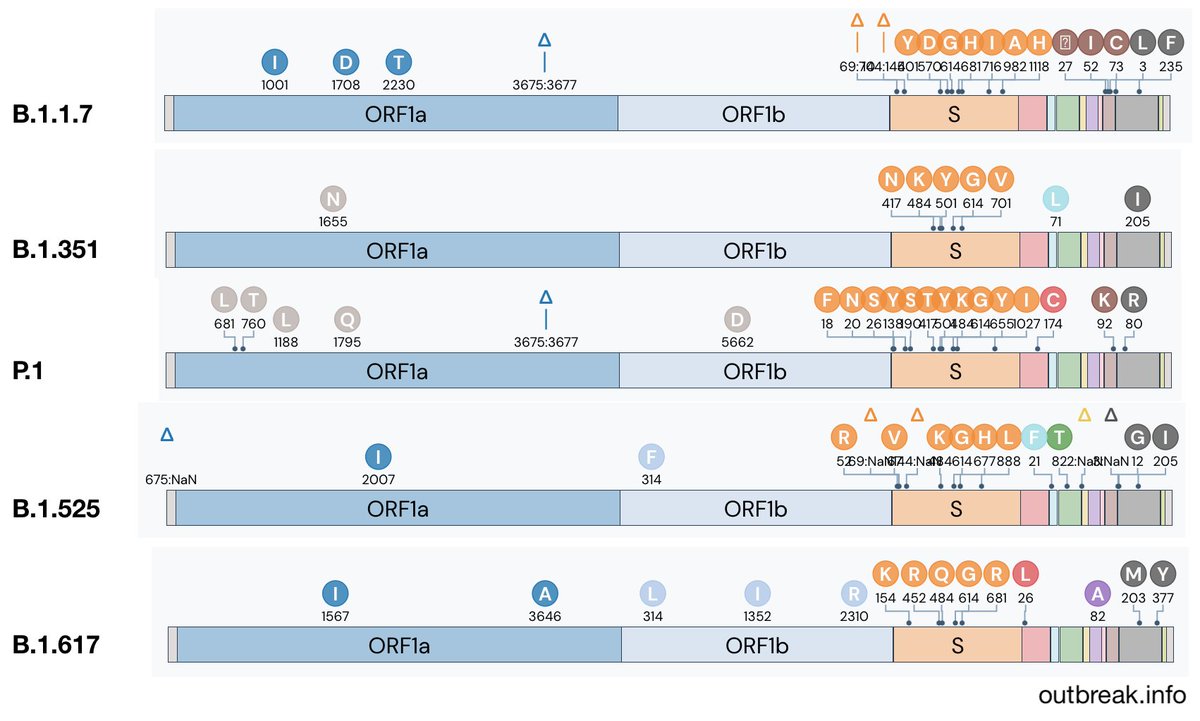

Since January, there has been frequent emergence of competing lineages with large numbers of spike mutations, but by-and-large B.1.1.7, B.1.351 and P.1 have remained at the forefront. 8/15

Examples of competing lineages of note include B.1.525 (with spike mutations Q52R, 69-70del, 144del, E484K, Q677H and F888L, common in Nigeria outbreak.info/location-repor…) and B.1.617 (with spike mutations E154K, L452R, E484Q and P681R, common in India outbreak.info/location-repor…). 9/15

Though there haven't been obviously superior competitors to B.1.1.7, variant viruses are continuing to emerge across the world. Genomic surveillance should also be global in its endeavor. 10/15

As discussed previously (

https://twitter.com/trvrb/status/1356997080976289794), the currently observed rate of evolution in S1 is rapid compared to the equivalent domain in influenza virus owing to accumulation of S1 mutations in the VOC viruses. 11/15

The million dollar question here is, of course, whether this pace of evolution will be sustained year-after-year. I don't have a good answer to this. 12/15

On one hand, convergence would suggest that in ~1-2 year's time SARS-CoV-2 will have arrived at its destination having stacked up all the relevant mutations that are currently emerging. 13/15

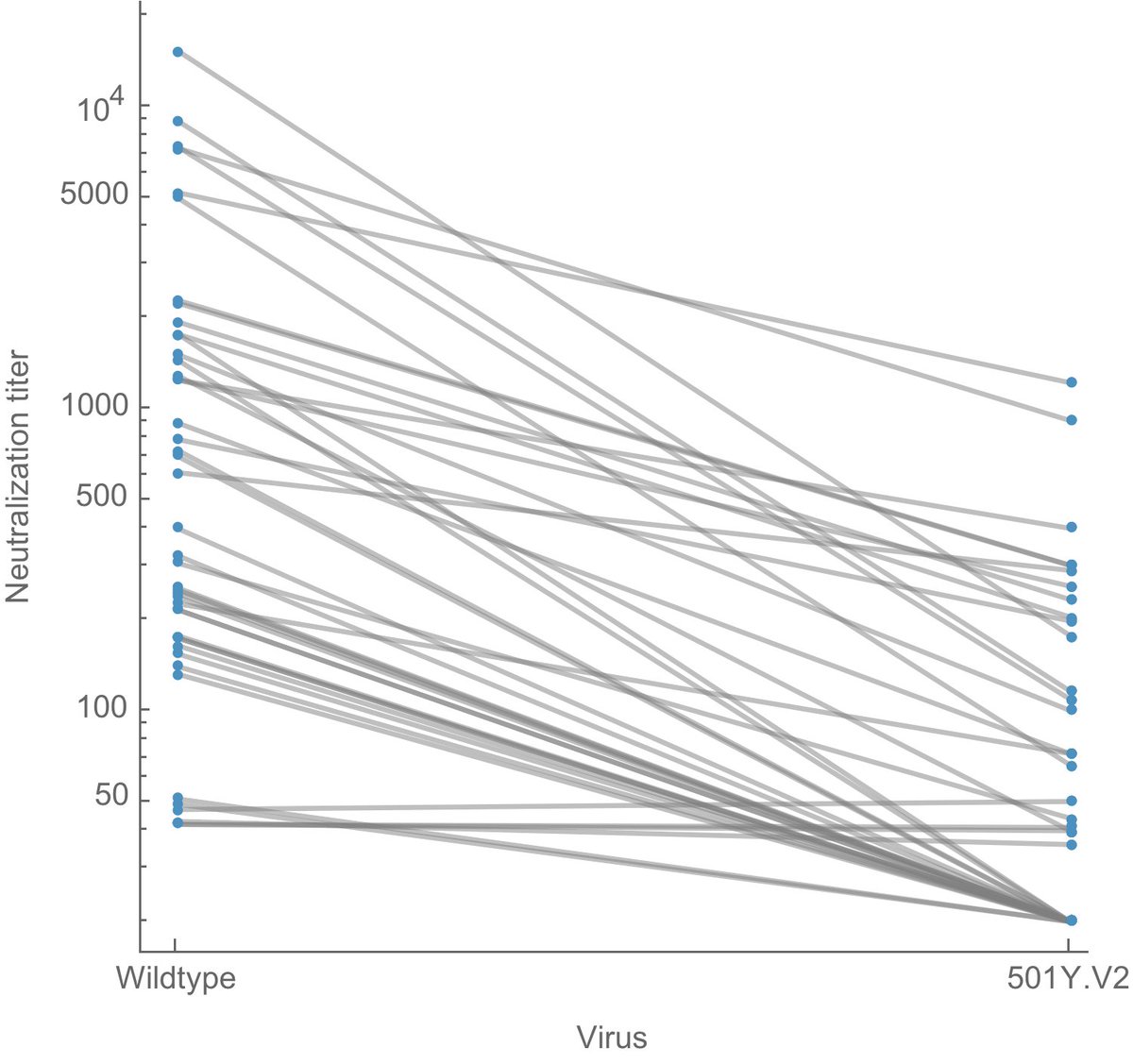

On the other hand, currently selected mutations are arising in a context of population immunity engendered to original "wild-type" viruses and immunity raised to antigenic drifted viruses like B.1.351 may push evolution in a new direction. 14/15

This continual cat-and-mouse scenario is what plays out with seasonal influenza, where new viruses emerge and spread, but leave a wake of population immunity that creates pressure for further evolutionary innovation. 15/15

(Sorry I've been absent during the past ~2 months. I needed a break from Twitter. I'll try to provide more frequent updates going forward.)

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh