Jesse Bloom's preprint has, of course, caused quite a stir. I wanted to try to explain a bit about the "rooting issue" discussed in the manuscript and also provide some hopefully clarifying phylogenetic trees. 1/15

https://twitter.com/jbloom_lab/status/1407445604029009923

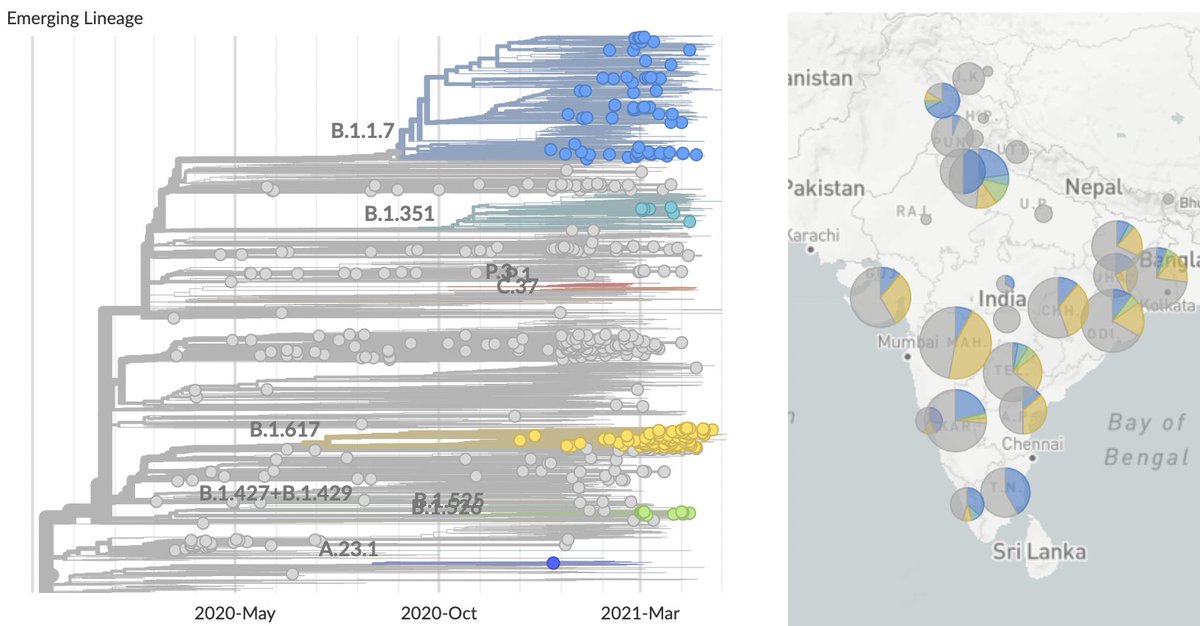

For this post, I've made a @nextstrain "build" targeted at SARS-CoV-2 genomes from Dec 2019 through Jan 2020, totaling 549 viruses. All code is here: github.com/blab/ncov-earl… and should be reproducible using a download of @GISAID data. 2/15

There is genetic diversity within these very early samples with much of it arising from a split in early transmission chains into lineage A and lineage B viruses (lineage B as in B.1.1.7). Lineage A and lineage B viruses are separated by mutations at sites 8782 and 28144. 3/15

There is uncertainty in exactly how to root the phylogeny, ie the virus that represents the common ancestor of all _sampled_ SARS-CoV-2 viruses. It could align with lineage A as shown here (nextstrain.org/groups/blab/nc…). 4/15

Or the root of the tree could align with lineage B as shown here (nextstrain.org/groups/blab/nc…). The root may not correspond exactly to the lineage A / lineage B split, but just examining A vs B will be sufficient for current purposes. 5/15

This rooting issue is really important as we can see that viruses from individuals with Huanan market exposure are predominantly lineage B viruses. If the root is at the base of lineage B, it fits with Huanan market as emergence location (nextstrain.org/groups/blab/nc…). 6/15

However, if the root is in lineage A then it supports (but does not necessitate) Huanan market as a secondary foci rather than the emergence location (nextstrain.org/groups/blab/nc…). 7/15

Although alternatively, one could hypothesize multiple zoonotic events of closely related viruses to explain this pattern as suggested by Bob Garry in this Virological post (virological.org/t/early-appear…), but this is in my eyes less parsimonious than a single spillover event. 8/15

Two primary methods of root placement give conflicting results. Placement by molecular clock prefers lineage B and placement by outgroup (via RaTG13 or other bat SARS-like viruses) prefers lineage A. This is detailed in @lpipes @ras_nielsen et al (academic.oup.com/mbe/article/38…). 9/15

Importantly, prior to Jesse's detective work, there were >77 genomes collected from Wuhan in Dec and Jan and shared publicly. These samples fall into both lineage A and lineage B (nextstrain.org/groups/blab/nc…). 10/15

As one might expect, the 13 sequences from BioProject SRR11313485 uncovered by @jbloom_lab also fall into both lineages A and B, with 8 out of 13 residing in lineage B (Table 1 of Bloom colored by identify at site 28144). 11/15

In this case, I completely agree that deletion of records from the SRA is alarming. However, I don't see what's to be gained from the deletion. Other Wuhan genomes clearly show both lineages circulating outside the market. 12/15

The samples in question are majority lineage B and are described in the Wang et al manuscript as from "early in the epidemic (January 2020)" and fit with general pattern of majority lineage B samples collected Jan 2020 from Wuhan. 13/15

I would view a comprehensive analysis of root placement with evidence from outgroups alongside genomic epi simulations ala @jepekar, Wertheim et al (science.sciencemag.org/content/372/65…) as fundamentally important to our assessment of COVID origins. 14/15

As I've said before, I believe both zoonosis and lab leak to be plausible hypotheses for COVID origins. I'm not pushing any narrative, just trying to figure out what's going on with this particular datapoint. 15/15

https://twitter.com/trvrb/status/1400237539445800960

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh