THREAD: Basil II’s Campaigns in Bulgaria (Part One)

#Byzantine #medieval #Bulgaria #varangian #warfare

#Byzantine #medieval #Bulgaria #varangian #warfare

Before we can talk about Basil’s conquest of Bulgaria, we need to provide some context and examine the Basileus first campaign and the failures that would shape his reign.

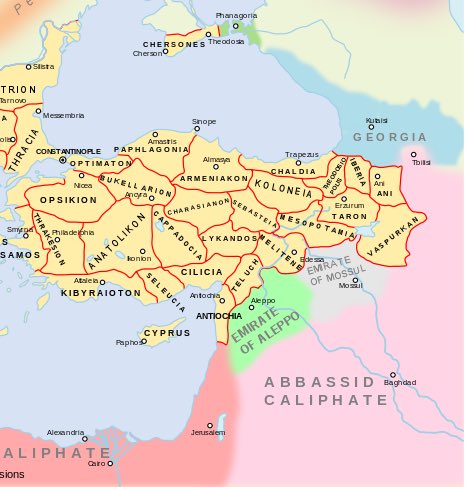

Basil’s dream had always been to succeed where no Basileus had before and conquer Bulgaria, but Basil’s early reign was marred by the rebellion of Bardas Skleros in Anatolia from 976-979. Tsar Samuel of Bulgaria took advantage of this unrest.

Samuel liberated the old capitals of Preslav and Pliska and launched raids ever deeper in Thrace and Greece. When the city of Larissa in Northern Greece fell to the Bulgars in 982, Basil had to act.

Basil gathered an army of 20,000 men and marched to Sredec (Sofia). Basil wanted to destroy Bulgaria in one decisive battle and the conquest of Sredec would open the way to the Bulgarian heartland in the mountains.

Once Basil set into his siege, problems began to multiply. His soldiers could not take the fortifications by storm and the Bulgars had burned all the crops in the area. To make matters worse, the Byzantines lost the cattle they brought with them to a Bulgar raid on their camp.

After 20 days of failed assaults on the walls, the Bulgar garrison sallied forth and inflicted devastating casualties on Basil’s forces. The Bulgars burned all the Byzantine siege equipment; the inexperienced Basil had put them too close to Sredec’s walls.

Unable to break into the city without siege engines, and without food, the Byzantines had no way to take Sredec. To make matters worse, Samuel had arrived with his army and encamped in the mountains to Basil’s rear.

The general Melissenos had been left with a large force to secure the Byzantine supply lines from Plovdiv to Sredec and prevent possible encirclement, but news had reached Basil that his force had marched back from their positions to quarters in Plovdiv.

The commander of the western armies, Kontostenphanos, convinced Basil the reason for Melissenos’ flight was that he was on his way to Constantinople to take the crown for himself and leave Basil at the mercy of the Bulgars. Basil broke camp and began the slow march home.

When the Byzantine army made camp that night rumors began to spread that the Bulgars had cut off the mountain passes and the army was trapped in enemy territory.

The next morning the Byzantine force began to lose cohesion as the men panicked at the prospect of an ambush. When Samuel saw the Byzantine retreat turn to rout he led his men into the valley and began the slaughter.

The Byzantine vanguard managed to push through the Bulgar lines to safety, Basil included. The elite troops of the vanguard took heavy casualties bringing the emperor to safety.

Some sources mention that there were contingents of elite Armenian and Varangian mercenaries in the vanguard. The presence of Varangians is likely as they had been serving as mercenaries in the Byzantine army for over a century.

It is possible the service these Varangians rendered Basil in this moment of crisis stuck with him and was a potent reason for his creation of the Varangian Guard.

Despite Basil’s escape, most of his army was dead or captured with the imperial insignia, a shameful defeat. Basil’s disaster at The Gates of Trajan, named for the ruined fort Trajan had built at the ambush site, created more headaches for the young Basileus.

Bulgar raids grew in intensity and began targeting Thessaloniki and even as far south as Corinth. The defeat also emboldened Bardas Phokas to rebel later in 986, sparking the rebellion that gave birth to the Varangian Guard.

Basil was bloodied but not broken, and once he pacified the eastern borders he returned to Bulgaria to wreak his vengeance on Samuel. Basil arrived in Europe in 1001.

Basil would not repeat his rash mistakes this time, and began an 18 year campaign to wipe Bulgaria off the map.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh