The word thingira, for example, which is gîkûyû for “hut” is “osingira” in Kimaasai.

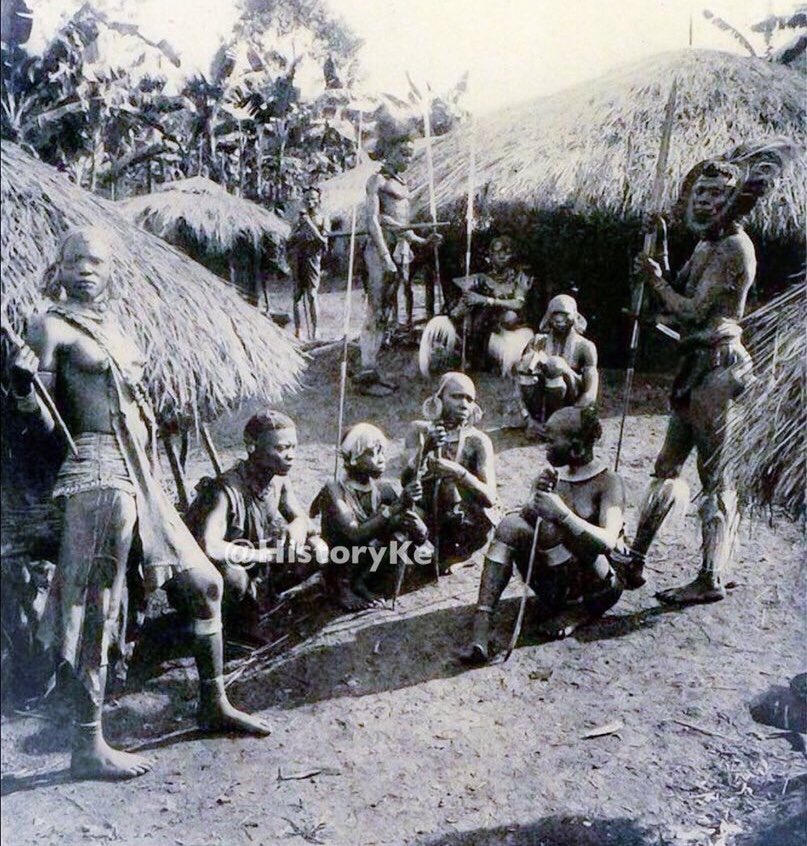

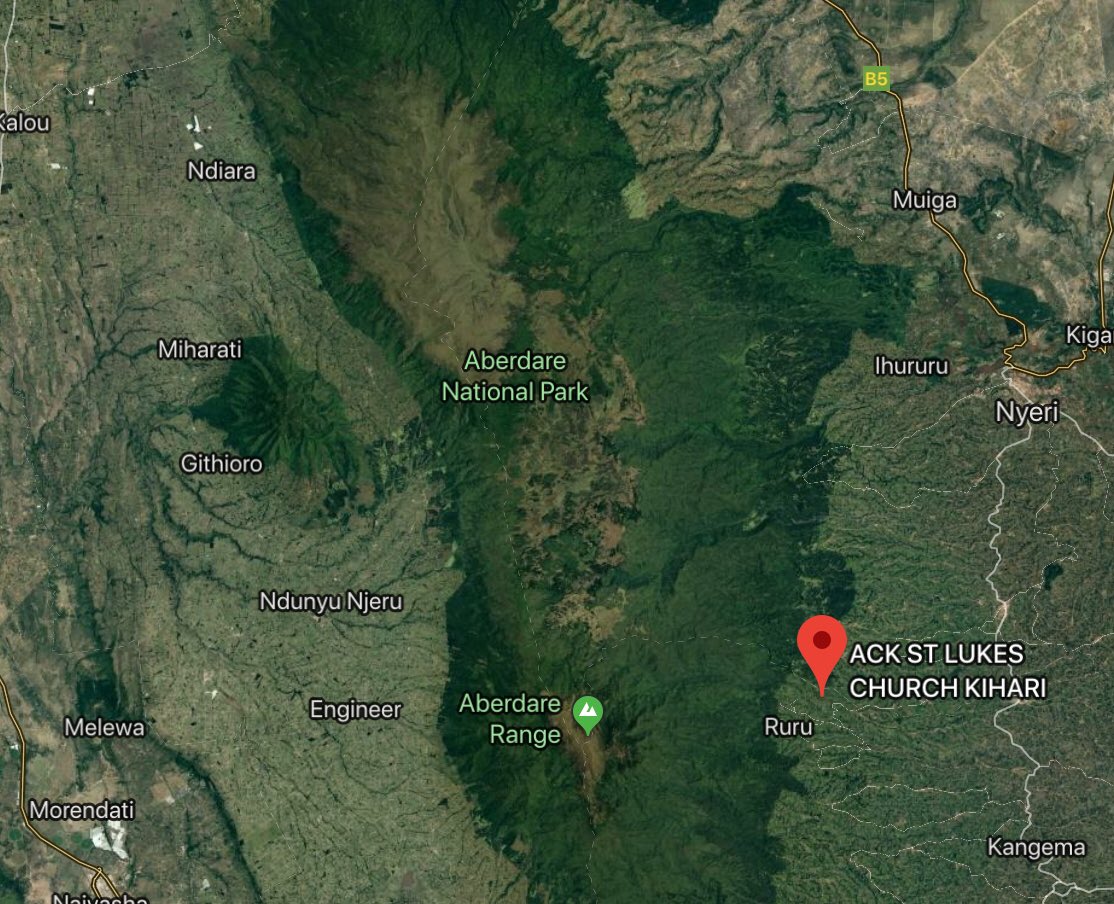

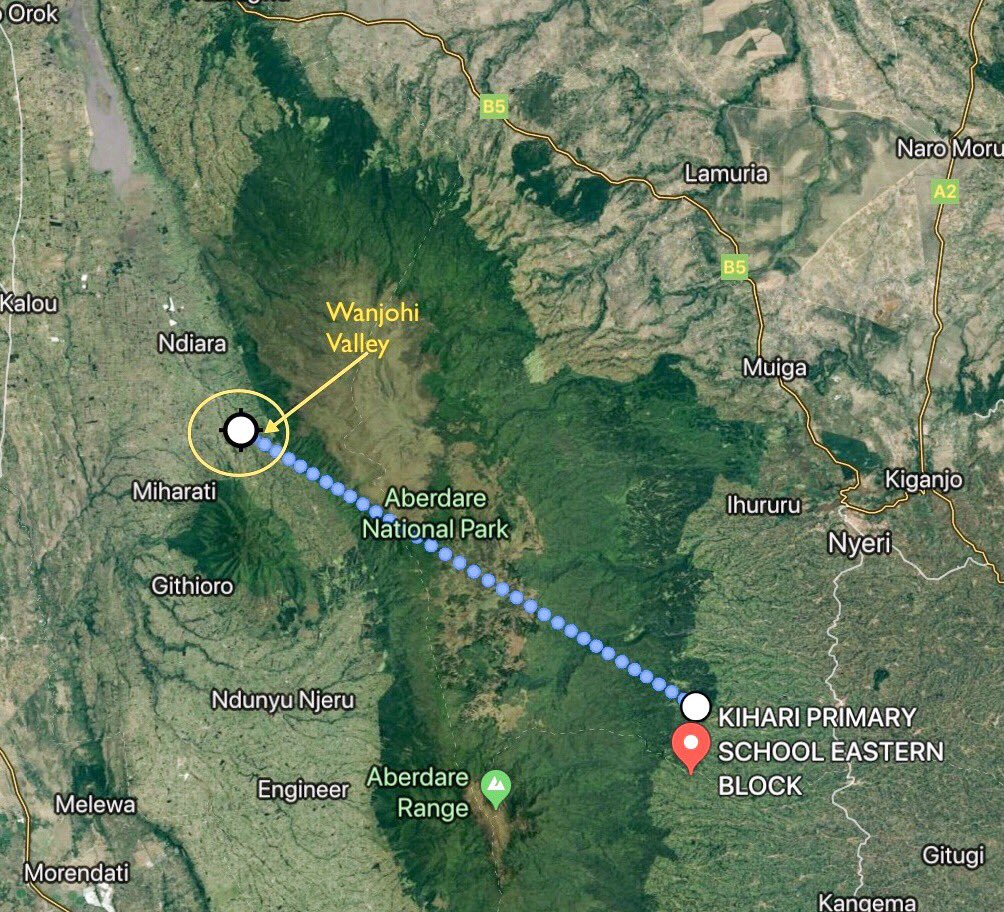

The attackers were said to number no more than fifty. They disappeared with their war loot into the forest, trekking through the forest and towards the other side of the Aberdares.

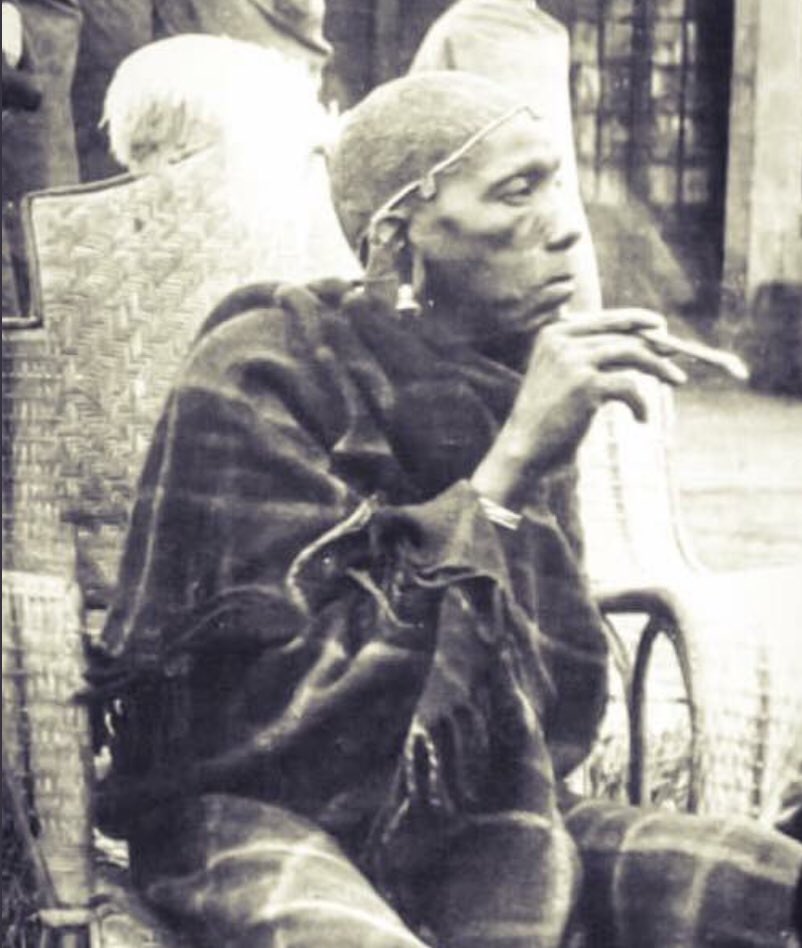

Wanjohi instructed his warriors to act in stealth, and with great caution, so as not to inflict collateral harm on his wife and child.

Back in Kîhari and the adjoining villages, word spread about the attack(s).

Undoubtedly, it was unforgivingly cold that night.

Wanjohi must have wondered how his son was coping with the cold. I doubt he slept that night.

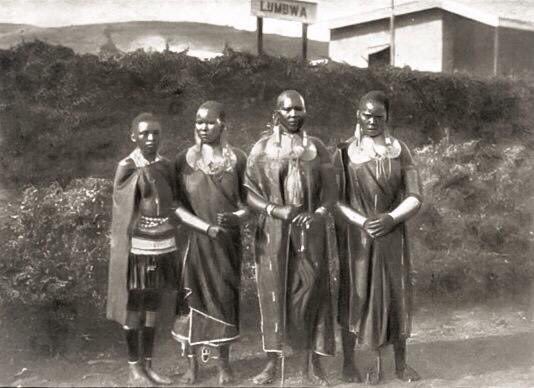

After a few hours, they emerged from thick forest on the other side of the Aberdares. It wasn’t long before Maasai warriors minding the stolen livestock nearby were tracked.

I wonder what was the reaction of the new arrivals.

But they must have gathered a lot of stones if this were the case. I have no information on the number of casualties on either side.