1/ Religion was another important link between #China and #Iran in both ancient and medieval times. This thread will briefly explore the Sino-#Iranian connection in the spread of three religions in China: #Buddhism, #Zoroastrianism, and #Islam.

#iranchina by @IranChinaGuy - B.F

#iranchina by @IranChinaGuy - B.F

2/ (Disclaimer: Each of these could be an entire topic, but as I am do this in my limited free time, I simply can't cover all three as well as I'd like. Please forgive anything left out, simplified, or overlooked. Follow me @IranChinaGuy and I will post more on each next week!)

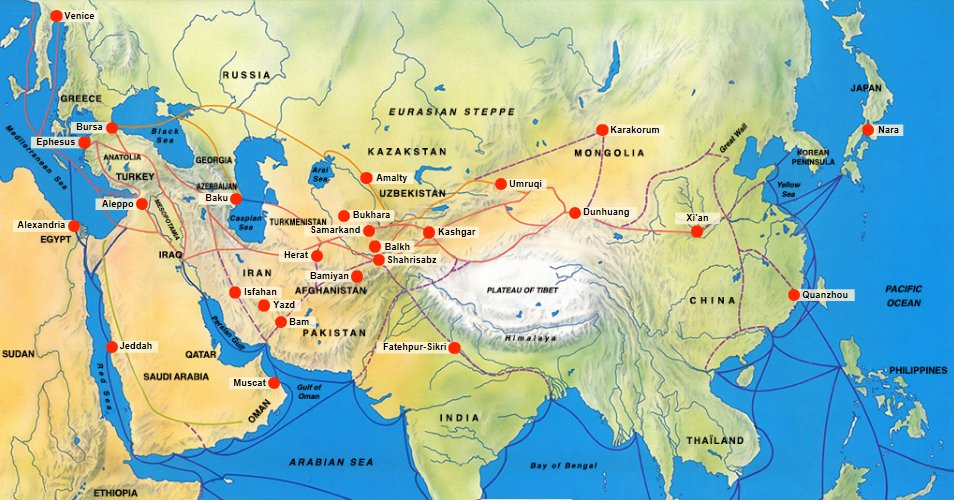

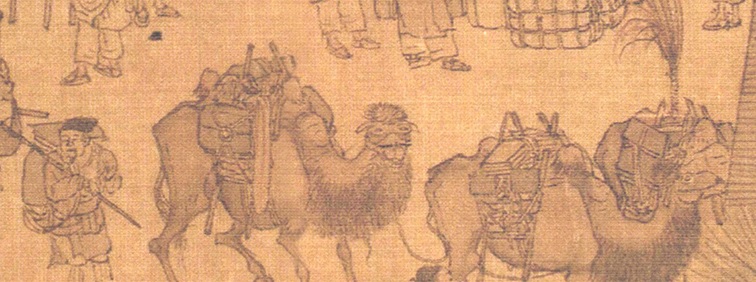

3/ We have already discussed the Parthian origins of Buddhism in China via An Shigao. In general, Buddhism entered China via Central Asian contacts with Parthia, Kushan, and other Indian and Iranian cultures. Many of the early translators came from these areas, although...

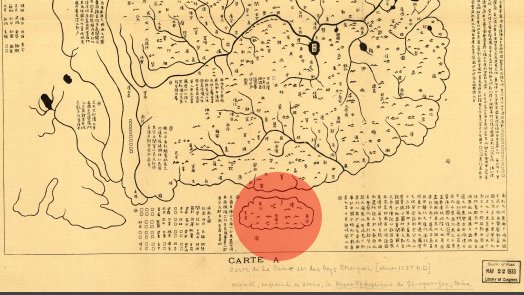

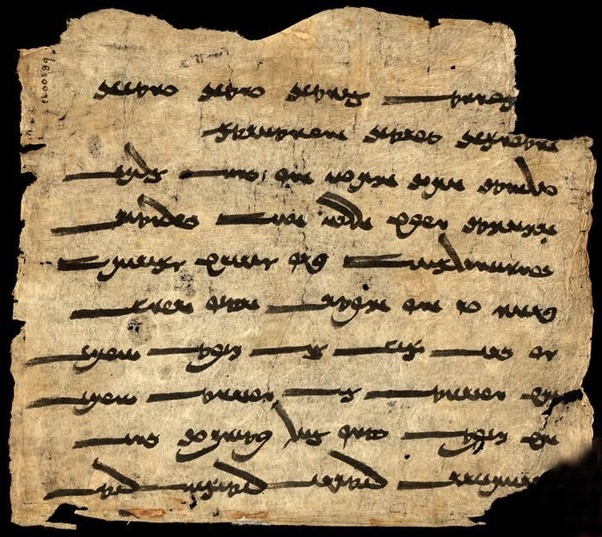

4/ ...they primarily translated into Sanskrit and were influenced by Indian traditions. More directly associated with the Sogdians and Persian culture was Zoroastrianism, 祆教 (Xiān jiào), which spread in China around 4th century CE. (Img: Sogdian Avestan text found in Dunhuang)

5/ Initially serving the needs of Sogdian communities along the Silk Road, Zoroastrianism later became localized in the 10th and 11th centuries. Although persecuted and nearly destroyed in 845 CE, under the Song dynasty (960-1279 CE) it became part of state religious rituals.

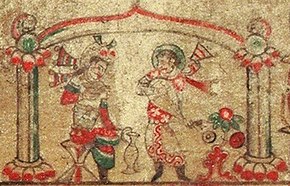

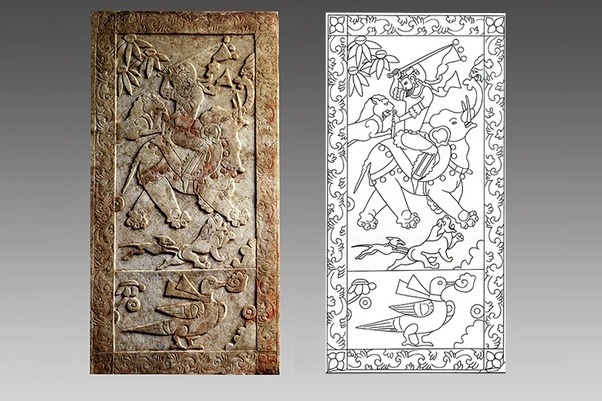

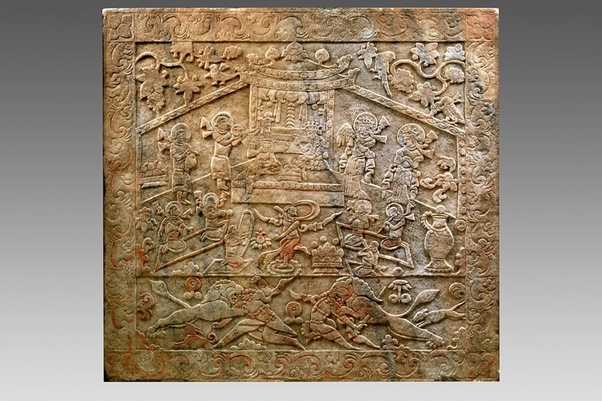

6/ It appears Zoroastrianism became increasingly nativized alongside Sogdian and Persian communities and their descendants, until they became indistinguishable from their neighbors. (Imgs: Tomb of Zoroastrian sabao (Elder, 薩保) Yu Hong in Taiyuan, 592 CE)

7/ Nevertheless, at one time Sogdian Zoroastrians were a vibrant community in China. This Tang-era (8th century) statue of a Zoroastrian priest, juxtaposed with its modern-day equivalent, shows just how familiar the Tang court was with Zorostrian traditions.

8/ Islam in China is yet another topic that could have it's own thread (and will next week!), but the short version goes something like this:

Islamic merchants are believed to have made contact with Tang China as early as 650 CE. As I mentioned previously, some were among...

Islamic merchants are believed to have made contact with Tang China as early as 650 CE. As I mentioned previously, some were among...

9/ ...the Arab and Persian merchants, pirates, and slaves of south China and the major cities. The high profile of Muslim merchants is one reason that Muslims were ignored in the 845 Great Anti-Buddhist Persecution, which also targeted Nestorian Christianity and Zoroastrianism.

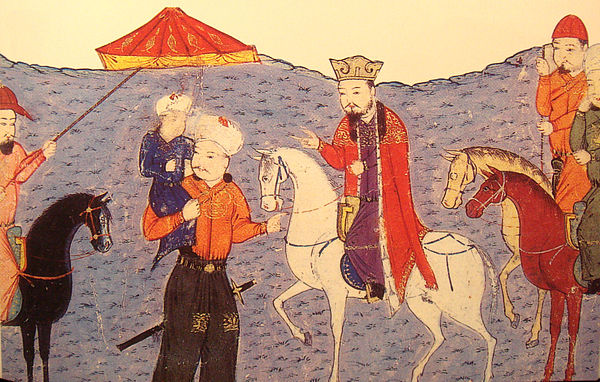

10/ Under the Mongol Yuan, Islam spread even further as many Muslims, Arab and Persian, moved to China thanks to new political and transportation networks with the Middle East. Mongol political practice also privileged minority groups, which allowed Muslim communities to thrive.

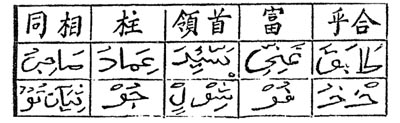

11/ Arabs and Persians intermarried and Islam was also nativized. Today, the term Hui (回) refers to sinicized Chinese Muslims, and the religious terminology of sinicized Islam reflects some Persian roots; for example, Imam is Ahong (阿訇), from the Persian Akhund (آخوند).

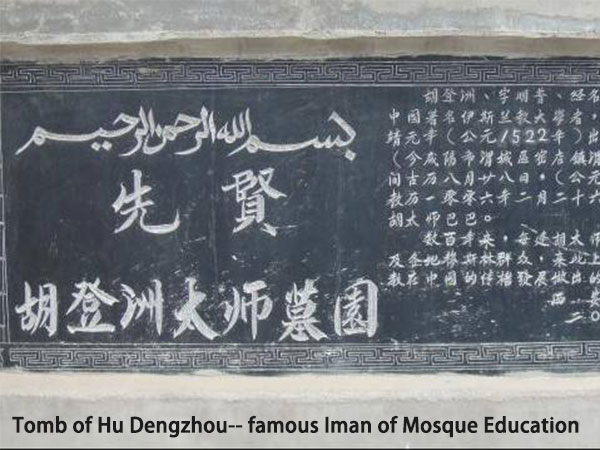

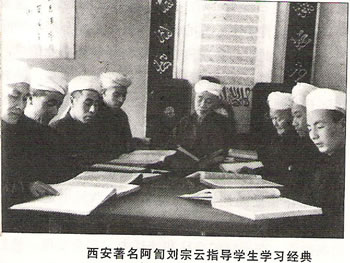

12/ At one time, Persian was considered an important religious language by this community. Hu Dengzhou (胡登洲), known for founding the Jingtang Jiaoyu (經堂教育) system for Islamic education in China, was known for his mastery of both Persian and Arabic. He helped codify the...

13/..."Thirteen Classics" of Islamic education that were to be taught in China, which included 5 Persians and 8 Arabic texts. To this day, these texts are studied in transliteration in China and read using a mixture of Chinese, Arabic and Persian grammar and pronunciation.

14/ However, the popularity of Persian was not to last. After the 16th century, for a variety of reasons that will be discussed in our next thread, the use of Persian declined among both the court and the Muslim population. Islam in China, however, was here to stay.

15/ See you next thread, where we will discuss the decline of Sino-Persian relations under the Qing dynasty and Safavid/Qajar Iran! - B.F @IranChinaGuy

And I promise more in-depth threads on Persian language, Zoroastrianism, and Islam in China on my personal twitter next week!

And I promise more in-depth threads on Persian language, Zoroastrianism, and Islam in China on my personal twitter next week!

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh