1/ Persian was an important admin. and religious language during the Yuan and Ming, but declined under the Qing (1644-1912).

On the rise (and fall) of Persian language use in China and the decline of traditional Sino-Iranian ties by the 20th century.

#iranchina by @IranChinaGuy

On the rise (and fall) of Persian language use in China and the decline of traditional Sino-Iranian ties by the 20th century.

#iranchina by @IranChinaGuy

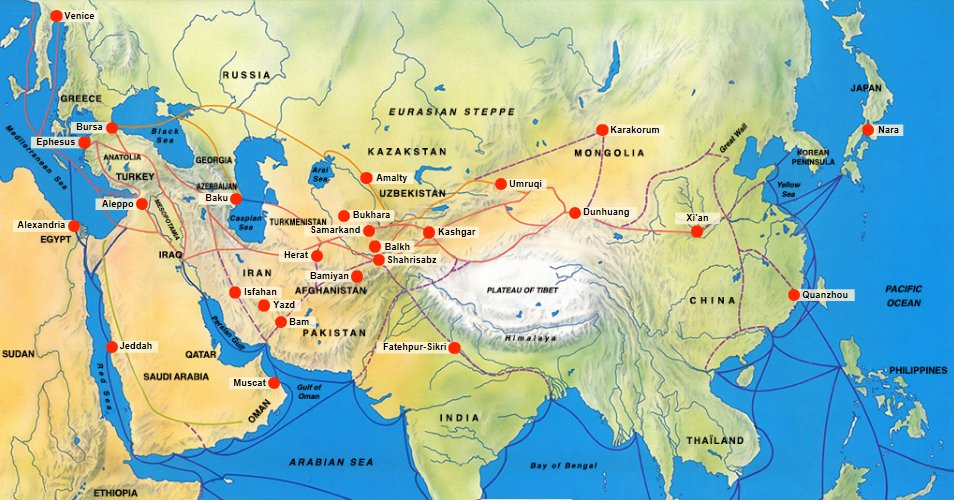

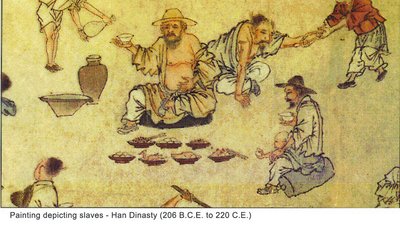

2/ During the Yuan, China and Persia were linked by Mongol rule, and Persian was one of the official administrative languages. A few Persians held important status as members of the semuren (色目人), an administrative class made up of non-Mongol, non-Chinese subjects.

3/ For example, Sayyid Ajall Shams al-Din Omar al-Bukhari, a Persian Muslim from Bukhara, was appointed by Kublai as governor of Yunnan in 1274, a fact mentioned by Marco Polo. Chinese sources record him as Sàidiǎnchì Zhānsīdīng (赛典赤·赡思丁).

(Img: Tomb in modern Yunnan)

(Img: Tomb in modern Yunnan)

4/ As a prestigious "courtly" language across the area of Mongol conquest, Persian was patronized by Mongol rulers even if Turkic was the more common language of the Semuren and the Muslim elites. In 1284, Kublai Khan established a Muslim school in the capital for “the sons of...

5/ "...officials and the rich”, likely headed by the Persian Efteḵār-al-Dīn. The translation of Persian texts was also in demand, and medical manuals like "Huihui yaofang" (回回藥方) were compiled by Muslim scholars from Persian and Arabic sources. However, with the rise of...

6/ ...the nativist Ming dynasty, there were few officials left at court who knew Persian. Ming (1368-1644) scribes continued translating proclamations into Persian and maintained tributary relations with Persian polities, but these were low-level, and should not be exaggerated.

7/ In Iran, as mentioned previously, Chinese potters crafted blue and white wares specifically designed for the Middle Eastern market, and in Safavid Iran (1501-1736) porcelain was highly valued by elites. Shah 'Abbas I is famous for moving Armenians in Isfahan to stimulate...

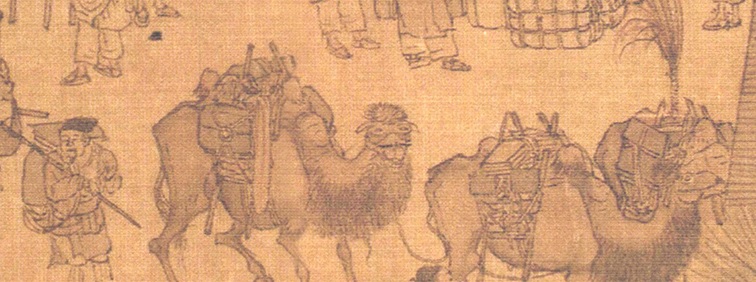

8/...the silk trade, but he also settled 300 Chinese potters in Isfahan to improve Iranian pottery techniques. Official Sino-Iranian contact was rare, but the flow of merchants, envoys, and tributaries official and unofficial from Iran and Persian-speaking polities continued.

9/ By the Qing (1644-1912), connections between Persia and China had become even more limited, as had the use of Persian. Partly due to the elevated importance of Turkic after the conquest of Xinjiang and other territories populated by Turkic speaking Muslims in 1755...

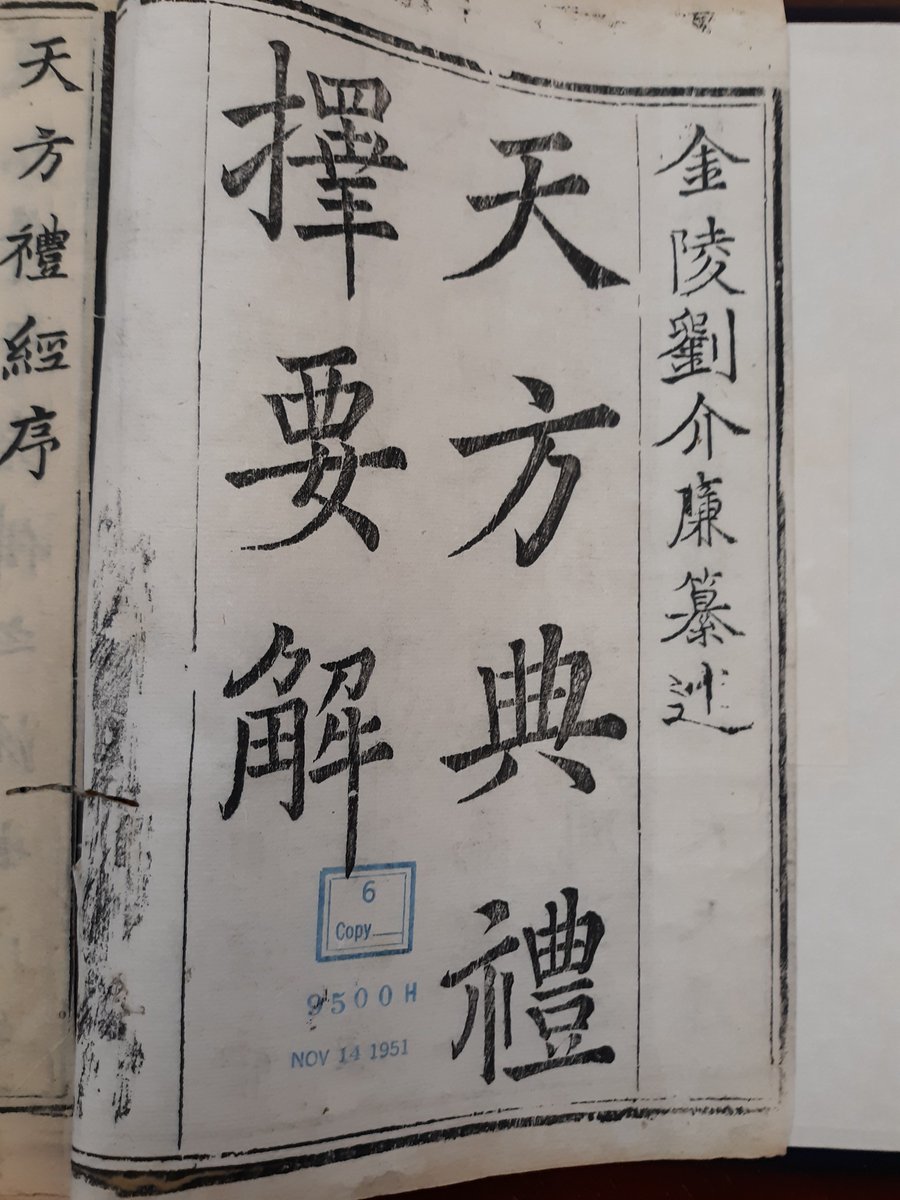

10/...and in part due to increased links between China and the Arab Middle East through networks of European colonialism. Persian, already rarely spoken, vanished almost completely after the spread of the Han Kitab (汉克塔布, Hàn kètǎbù) a collection of native Chinese writings...

11/ ...that attempts to harmonize Islamic and Confucian thought, and later by 19th century Chinese Islamic revivalists like Hu Songshan who championed Arabic texts, as part of the global Islamic revival movement. David Brophy gives a dim assessment of Persian in the late Qing:

12/ “For Qing officials, Persian was the language of a set of relatively insignificant tributary polities to the west of Xinjiang...The court had little to no knowledge of Iran as a distinct political actor, nor did it have direct diplomatic contact with Mughal India, and it...

13/ "...therefore saw no need to enhance its ability to communicate with the outside world in Persian.”

By 1900, traditional ties between China and Iran had lost their earlier significance. Most Iranians in China had assimilated, political connections lapsed, and economic...

By 1900, traditional ties between China and Iran had lost their earlier significance. Most Iranians in China had assimilated, political connections lapsed, and economic...

14/ ...networks like the Silk Road had been replaced by the global trade networks of European colonialism.

At the same time, new forms of political and intellectual contact emerged from a common search for modernity. Once connected by merchant caravans and imperial decrees...

At the same time, new forms of political and intellectual contact emerged from a common search for modernity. Once connected by merchant caravans and imperial decrees...

15/ it was now European steamships, railroads, and newspapers that created new opportunities for Sino-Iranian connections that had never existed before. it was now European steamships, railroads, and newspapers that created new opportunities for Sino-Iranian connections.

16/ Internationalism, Constitutionalism, and Pan-Asianism were at the heart of a new discourse that compared China to Iran in political terms, leading to significant developments among Iranian leftists in the decades to come.

Which will be the subject of our next thread!

Which will be the subject of our next thread!

We have now finally reached my research! Hooray! I'm very excited to start sharing with you the results of my dissertation, "China and the Iranian Left: Transnational Networks of Social, Cultural, and Ideological Exchange, 1905-1979". - B.F @IranChinaGuy

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh