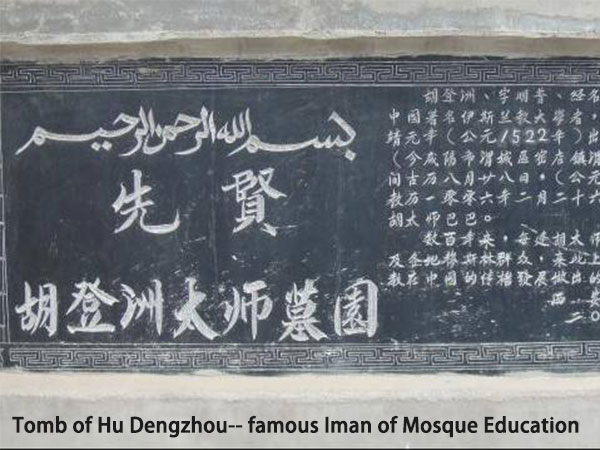

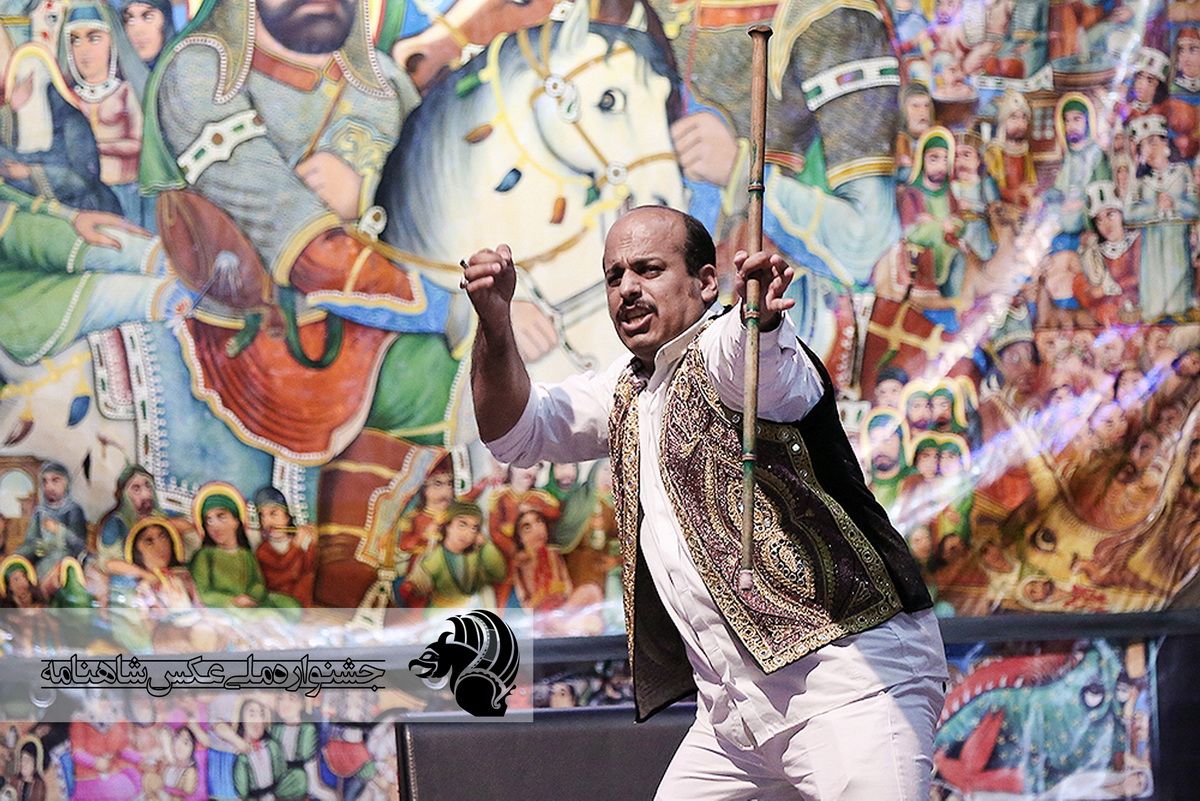

If you ever watched a Morshed (storyteller) performing from scenes of battles,heroes,infernal serpents and paradise birds, you know the absolute joy of Naqali,the art of storytelling. This is Morshed Mirza Ali whose family have been storytellers for generations. 1/17 @GolnarNemat

These days brilliant women storytellers are part of this traditionally male-exclusive profession. This is Sara Abbaspour; one of Morshed women today. The staff stick is a crucial part of performing, used to dramatize and to point to the painted scenes. 2/17 @GolnarNemat

In 19th century Persia forms of storytelling ranged from literature and oral anecdotes to themes of romance, chivalry and history of Shi'a Islam. Today we know Naqali mainly as reciting the epic of Shahnameh (Book of Kings) by 10-11th c. poet, Ferdowsi. 3/17 @GolnarNemat

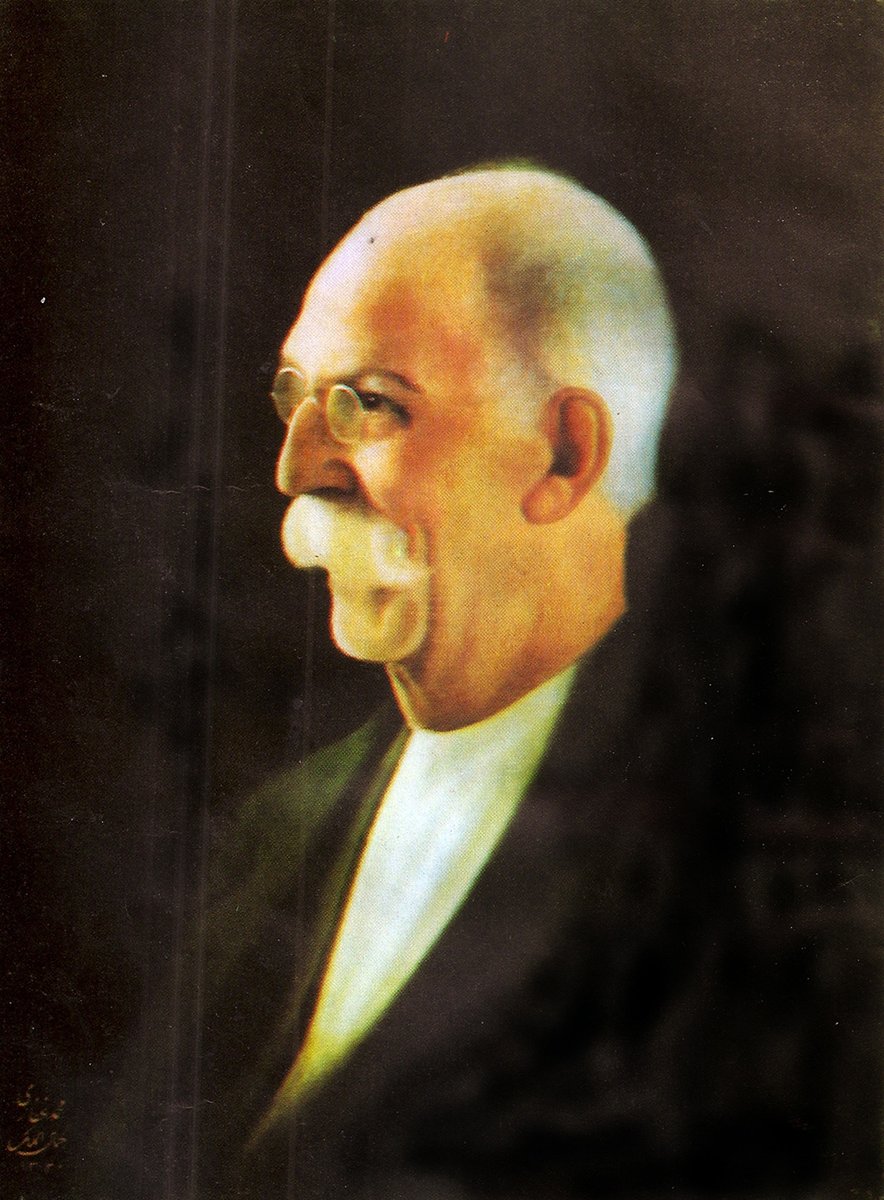

why is that, you ask? As part of his modernization agenda and to build a national identity, In 1940s the Pahlavi king Reza Shah encouraged Shahnameh as the only acceptable form of storytelling. Others, including folklore and religious forms, fell out of favor. 4/17 @GolnarNemat

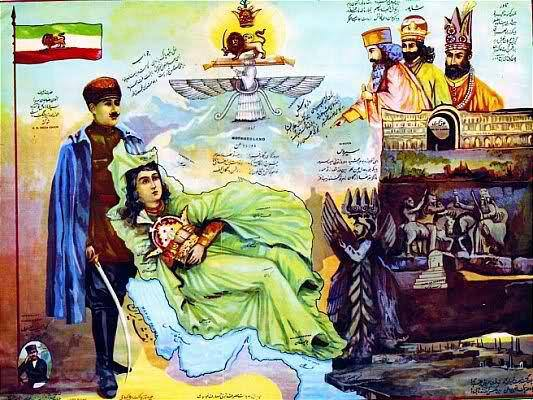

The religious storytelling,called Pardeh-Dari, did have a comeback later along with the theater of Ta'ziyeh— a form of passion play, if you will. That is a story for another time, but for now we are concerned with the Pardeh painting. Here's one by Qullar Aghasi.5/17 @GolnarNemat

Today both religious and epic paintings are known under Coffeehouse Painting, an inaccurate term. Coffeehouses were among places of gathering for Naqali but not the only ones. That's why Pardeh is so fascinating: one could carry it around and mount it anywhere.6/17 @GolnarNemat

The earliest example of Pardeh i.e. painting on a roll of canvas to be moved and used as accessory of performance (vs. murals) dates back to late Zand-early Qajar(1751-1794). 7/17

This form of art is really understudied because it's often considered unrefined and 'poor painting.' In fact, most of Pardeh artists are unknown to us until late 19th-early 20th century, when Abbas al-Musavi and others enjoyed popularity. 8/17 @GolnarNemat

By mid-20th century Pardeh found collectible value and artists were commissioned to paint them. Some of them were even gold-inlayed, like this one by Abdallah Musavar. Originally, though, Pardeh was an accessory of performance, meant to be seen by all. 9/17 @GolnarNemat

Artists of religious Pardeh also painted those with themes of epic and romance. They were apprentices of famous families who basically owned the craft; such as Ghaffari family, among whom we know Kamal al-Molk. But, there was a strict hierarchy in the craft, 10/17 @GolnarNemat

which was passed down for centuries in each family. Musavvar al-Mulki’s father, a renowned painter of Isfahan, famously joked “We don't have blood in our veins, but paint." No joke. 11/17 @GolnarNemat

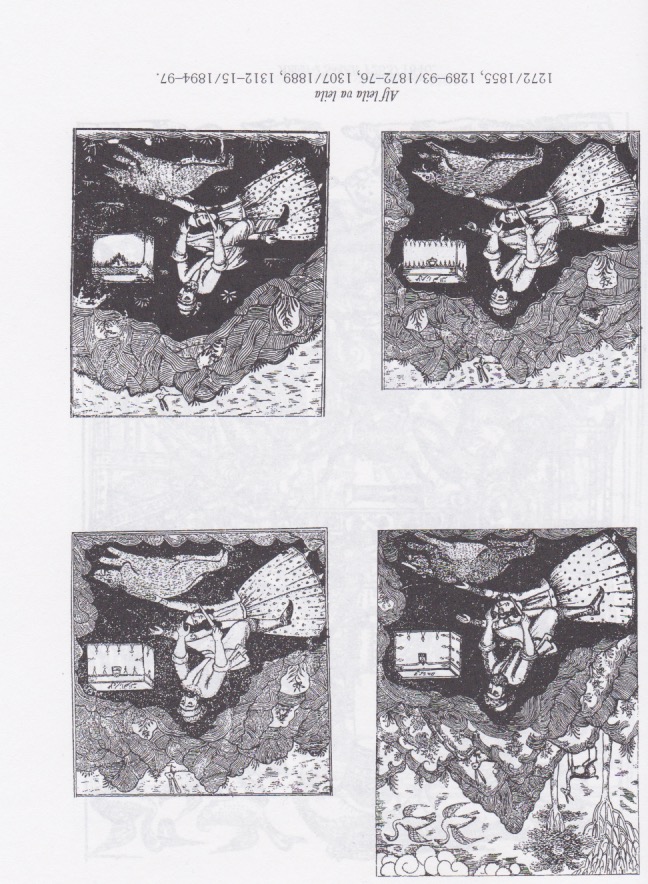

Best in the craft became royal painters. Then, painters who made art for the market, including lithographed illustrations, popular stories and newspaper, such as this lithographed print folio from Alf Laeila va Leila (1855-1872). 12/17 @GolnarNemat

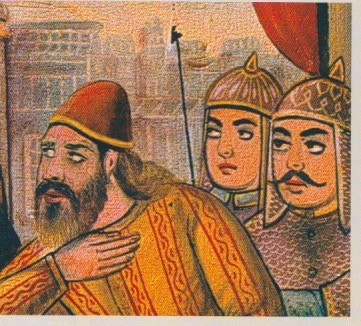

The lowest in the trade were apprentices of the second class and made architectural tiles and textile. These were the often-anonymous painters of Pardeh paintings. This tile mural from Tekyieh Movaven al-Molk (1903, western Iran) is a good example. 13/17 @GolnarNemat

See the two figures seated next to the Omayyad caliph, Yazid (the one on the throne)? They look like European envoys, right? Below a line reads ‘bringing of the prophet’s [captured] family, may God’s praise be upon them, to the malevolent Yazid’s court.’ 14/17 @GolnarNemat

This is the kind of social commentary slipped into Pardeh too. Morsheds of Pardeh Dari (religious storytelling) used these paintings to lead audiences into the battle of good and evil, extrapolating anecdotes of early Islam to their contemporaneous time. 15/17 @GolnarNemat

You may ask, why religious paintings and not epic ones? Because this particular form was unique to its historical time in structure and in performance. It was almost entirely based on oral anecdotes and therefore, varied a lot. 16/17

What were these paintings about? Stay tuned when I talk about the stories and the captivating performance of Morshed tomorrow. 17/17 @GolnarNemat

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh