That’s because if you came here at the beginning of the 1800's, it wouldn't be there at all.

The story of how they ended up in Windsor takes us back to the heyday of the British Empire & to the ancient world of Roman Libya. It shows how the imperial mind imagined ruins of the past & plundered its dominions.

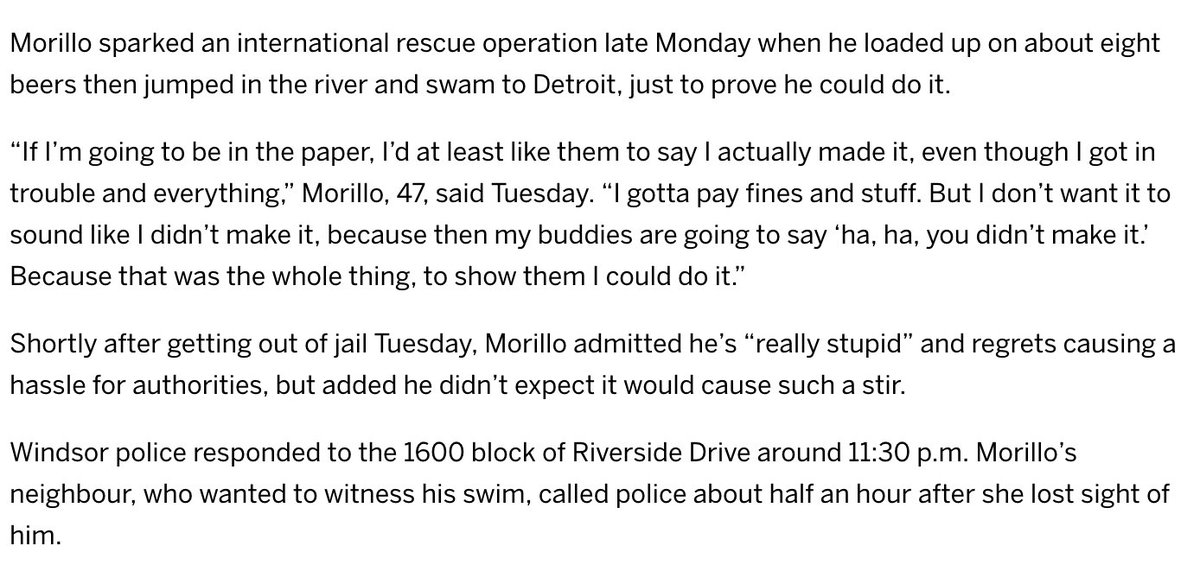

The sight struck them both. Earle even painted this watercolour, showing the sand dunes rolling over the stones.

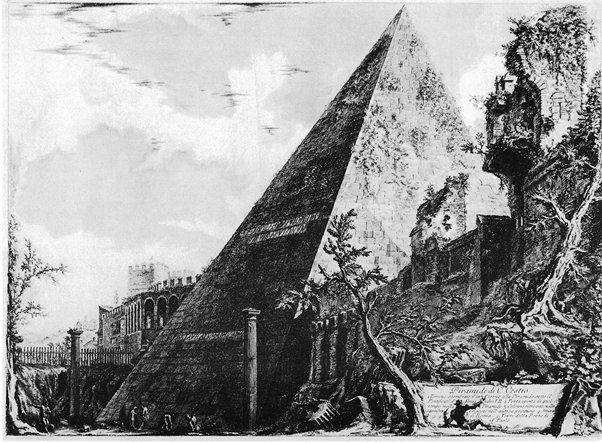

Emperor Septimius Severus was born there, & lavished it with wealth. He turned it into the 3rd-most important city in Africa, to rival Carthage & Alexandria.

A great tsunami in 365 devastated it, then the invasion of the Vandals in the 5th century & Muslim armies in the 7th finally left the city in ruins.

In the C17th, 600 columns from Leptis were taken by Louis XIV for use in his palaces at Versailles & Paris. Its columns can also be found in Rouen Cathedral.

Captivated by the columns of Leptis, Warrington persuaded the local Governor that, on behalf of the British crown, he should be able to “help himself” to the ruins.

However, he became convinced that his gifts would be received gladly, & arranged for them to be transported on his ship, The Weymouth.

The idea of foreigners taking these stones for themselves caused a great uproar.

As a consequence, Warrington collected fewer than planned. Today, 3 large columns he abandoned still lie on the beach.

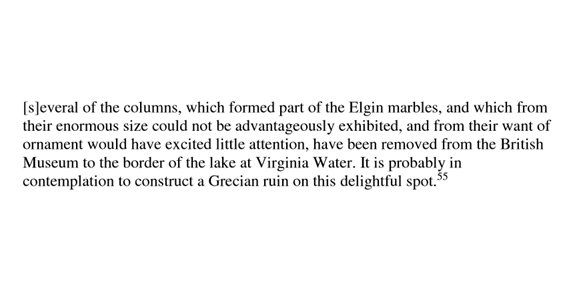

Experts in the British Museum, he recounted, were not “at all impressed or convinced of the value, either aesthetic or intrinsic, of the cargo.”

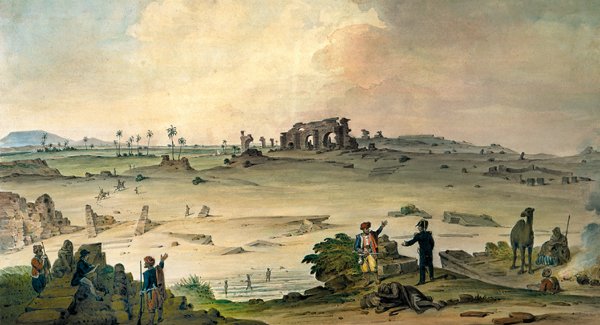

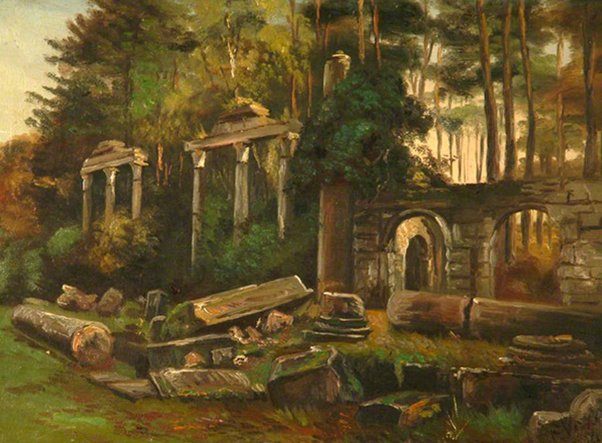

For instance, these ruins at Hagley Castle, Wimpole’s Folly & Schönbrunn, Austria were all built in their current state.

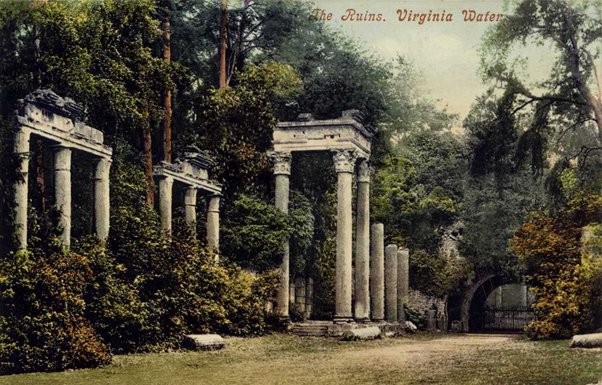

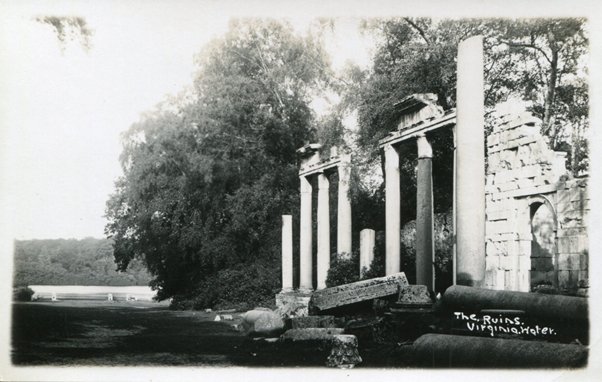

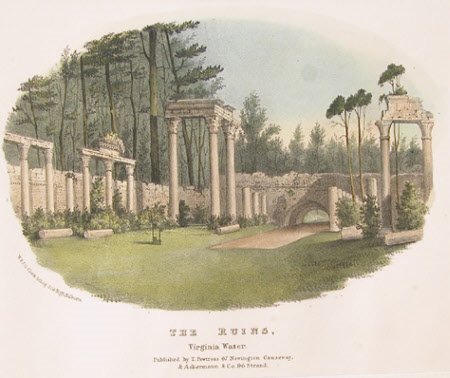

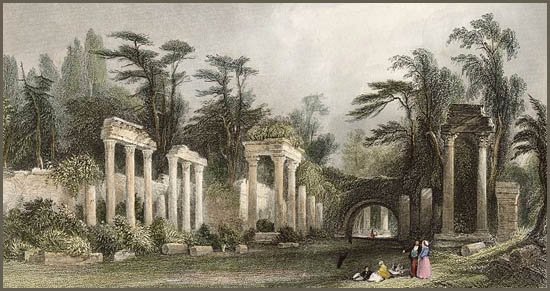

No designs or sketches have survived of how Wyatville wanted the ruins to look, & it seems he relied quite heavily on improvisation.

He added a chipped cornice to a nearby road bridge so it looked like an arch in a city wall.

One architect commented on the difficulty of creating authenticity: “if the mosses and lychens grow unkindly on your walls…if the ivy refuses to mantle over your buttress…you may as well write over the gate, Built in the year 1772.”

His creation, named fancifully “The Temple of Augustus”, was designed to evoke “ruin-ness”, but it was an illusion.

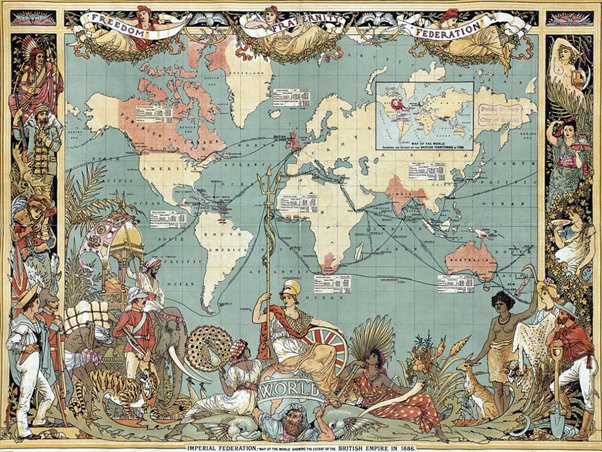

During the 19th century, the “Imperial century”, Britain added around 400 million people & 10 million square miles to its control.

“As the Romans purportedly settled and civilized Britannia, so Britain hoped to do for their own empire.” (Kacie M. Alaga)

In George IV’s official 1821 coronation portrait, you can even see classical columns in the background, marking him as the inheritor of an ancient right.

They mostly focused on the picturesque arrangement of the ruins.

In these paintings, the Virginia Water Ruins become a site of unsettlement & unease.

For Victorian architects, it seemed the next logical step was to build the imaginary ruins themselves.

Were the viewers of the false ruin supposed to wonder, as Gustave Doré did in 1872, whether London too might one day lie in ruins?

Virginia Water raises the spectre of the ruin being used to create a false reality, a false past.

What makes a ruin “real”?

Who owns a ruin?

Can a ruin be ruined?

ecollections.scad.edu/iii/cpro/app?i…