Differences between genealogies aren’t always a problem.

People can be referred to by different names in different circles/sources.

That said, the differences between Matthew’s and Luke’s genealogies are substantial.

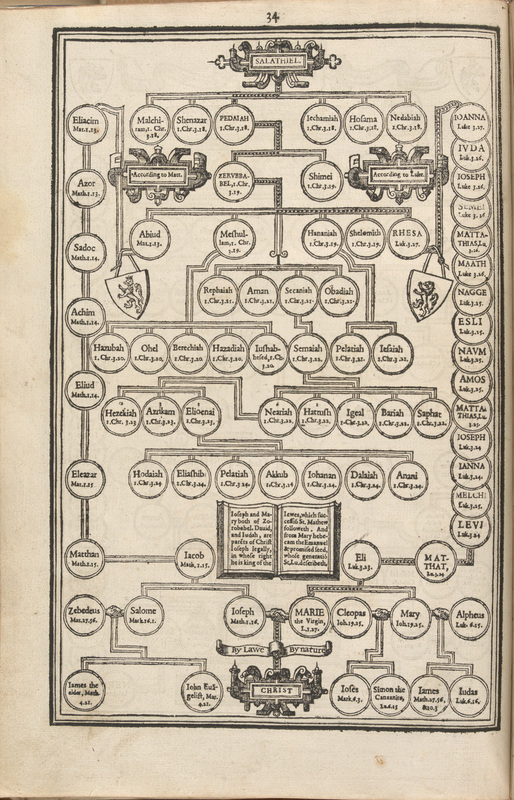

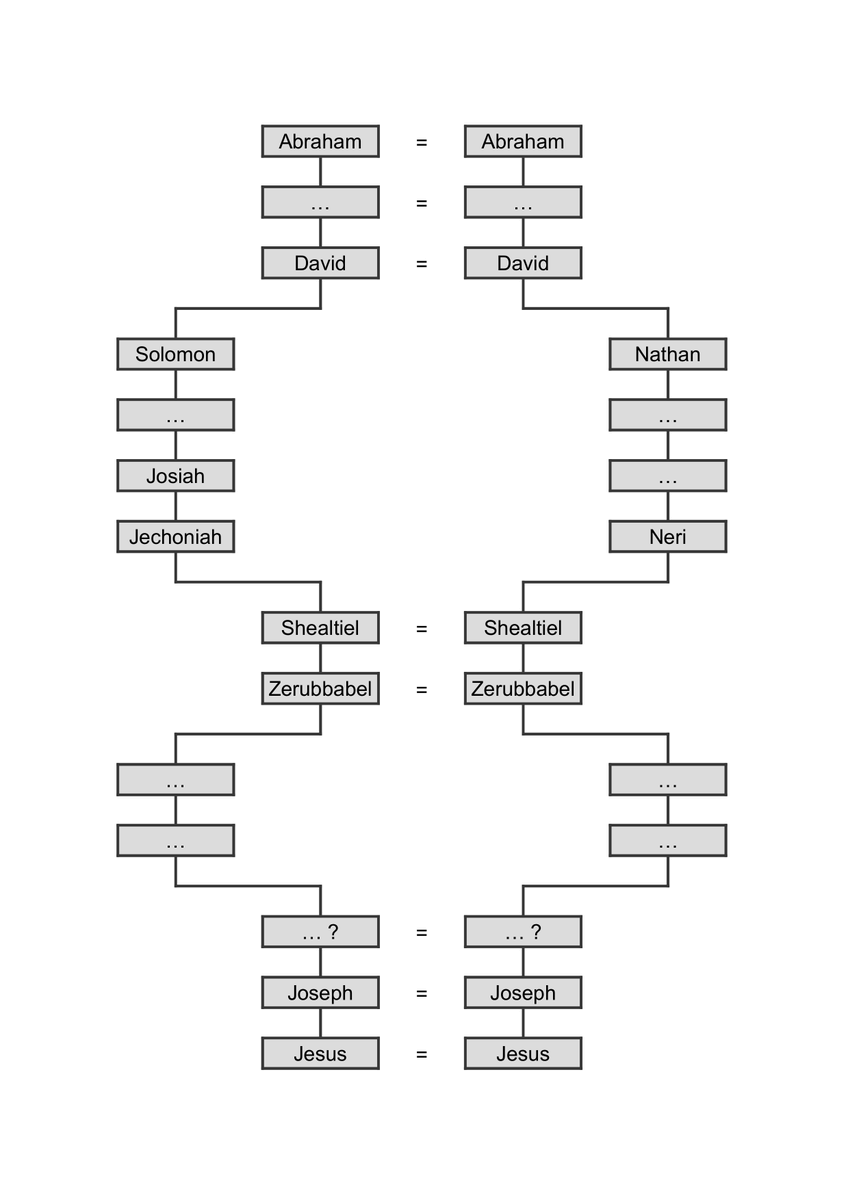

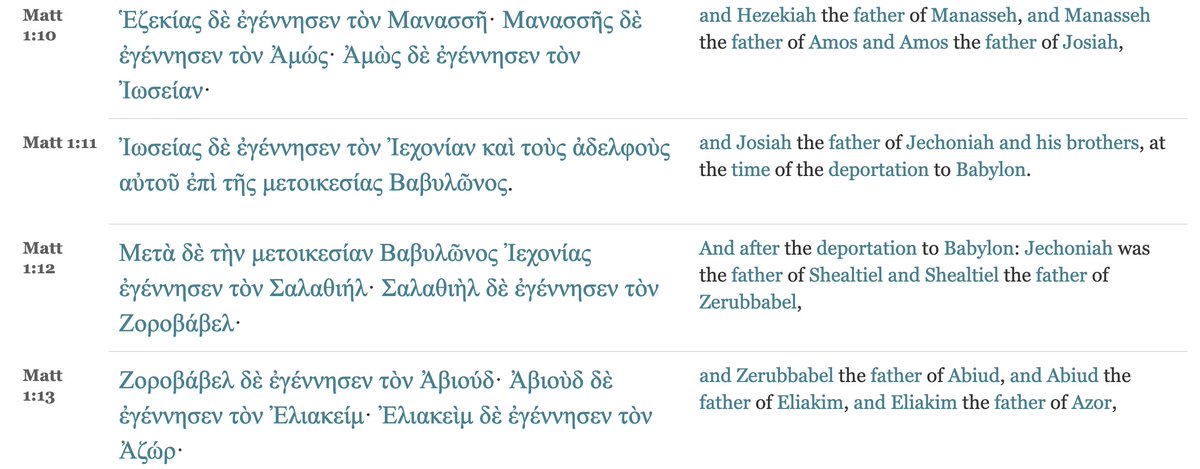

Matthew connects Jesus back to David by means of Solomon,

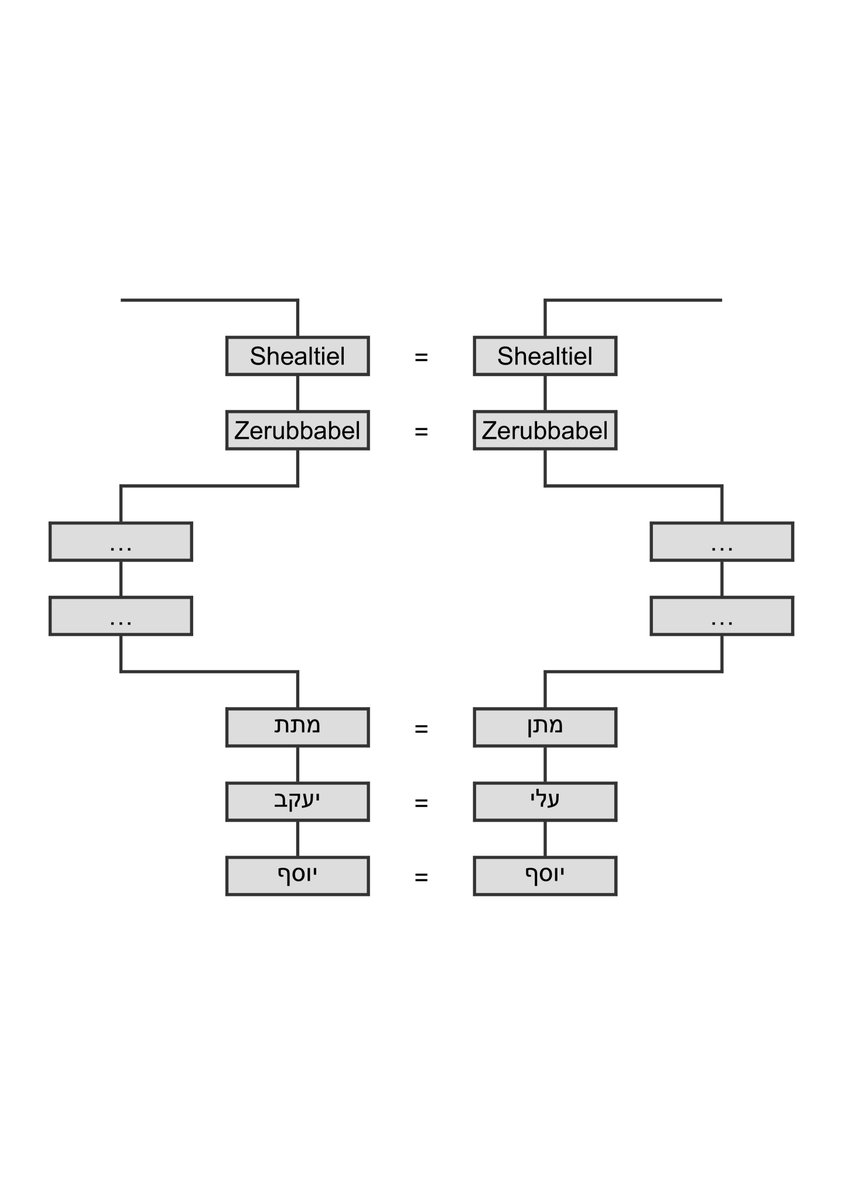

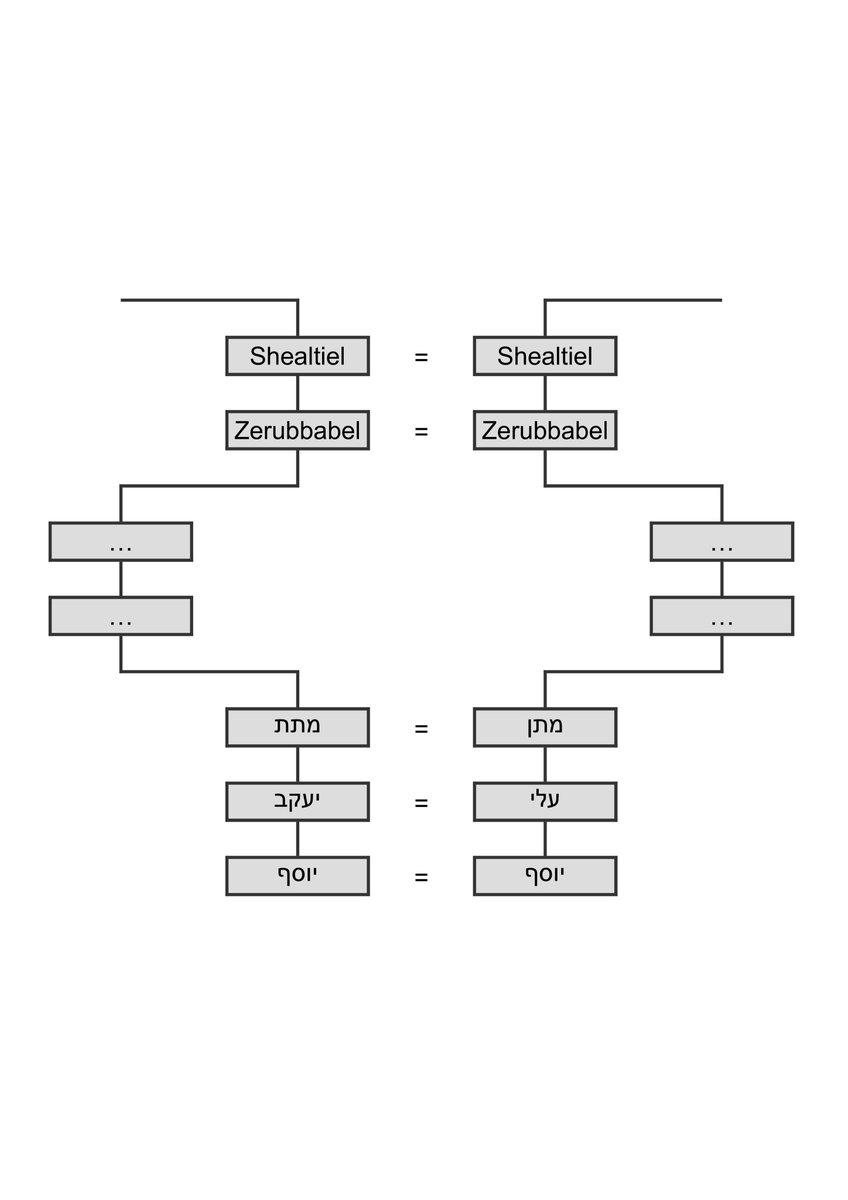

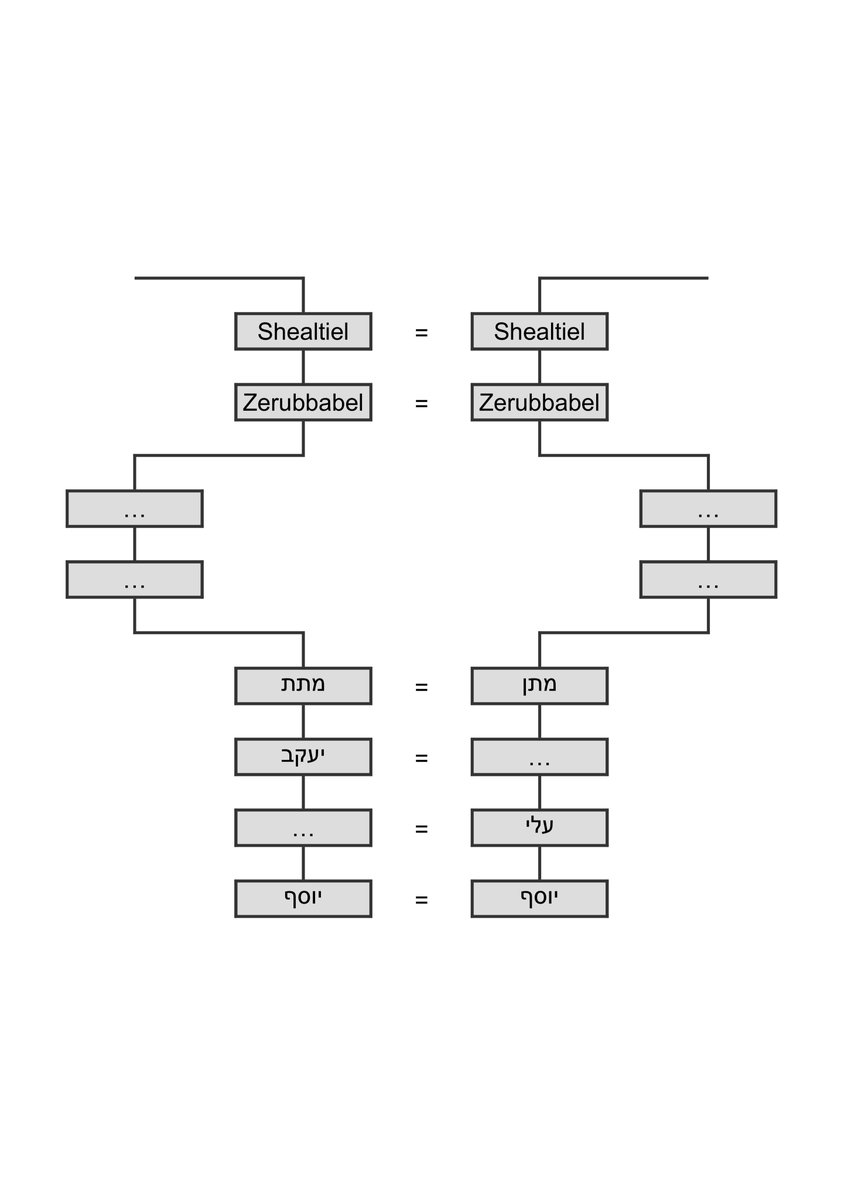

In addition, Matthew connects Joseph back to Zerubbabel by means of {Jacob, Matthan, Eleazar,...},

while Luke does so by means of {Heli, Matthat, Levi,...}.

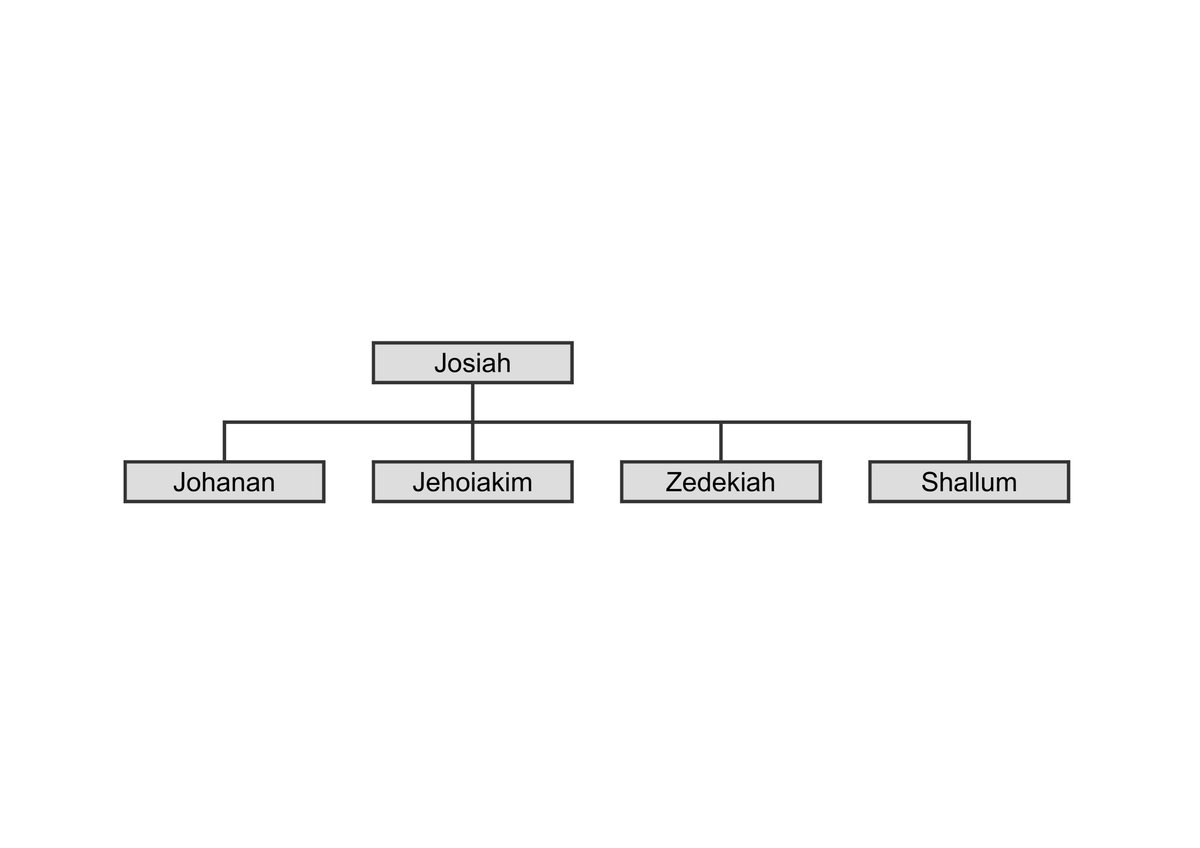

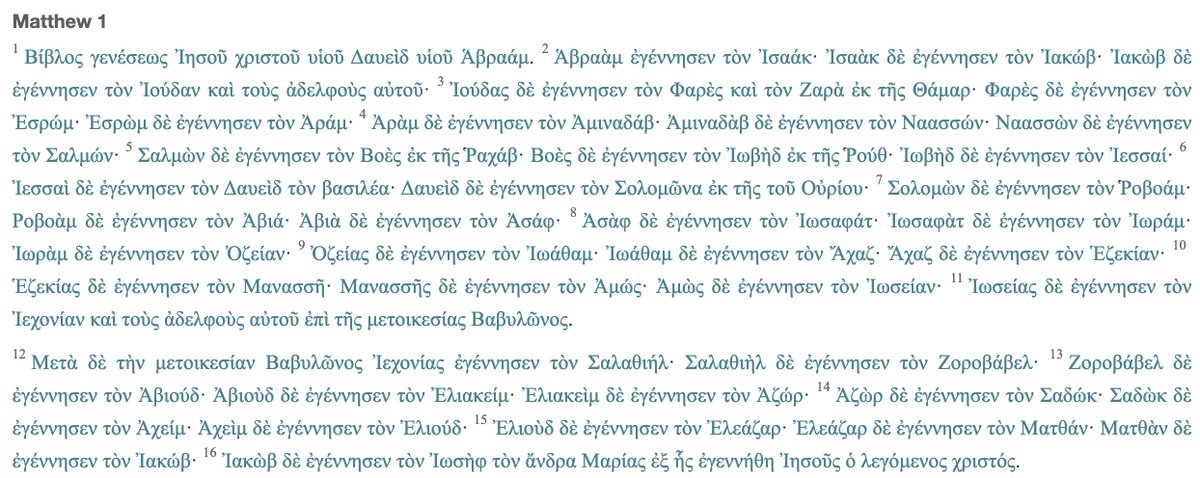

(1). broad agreement from Abraham to David,

(2). divergence over the era of the Kings (with Matthew’s line headed up by Solomon and Luke’s by Nathan),

(3). reunison in Shealtiel and Zerubbabel,

(5). finally, reunison in Joseph and Jesus.

Fine.

So, how are we meant to make sense of all these things?

which seems to be the case here.

#HereGoes

——————

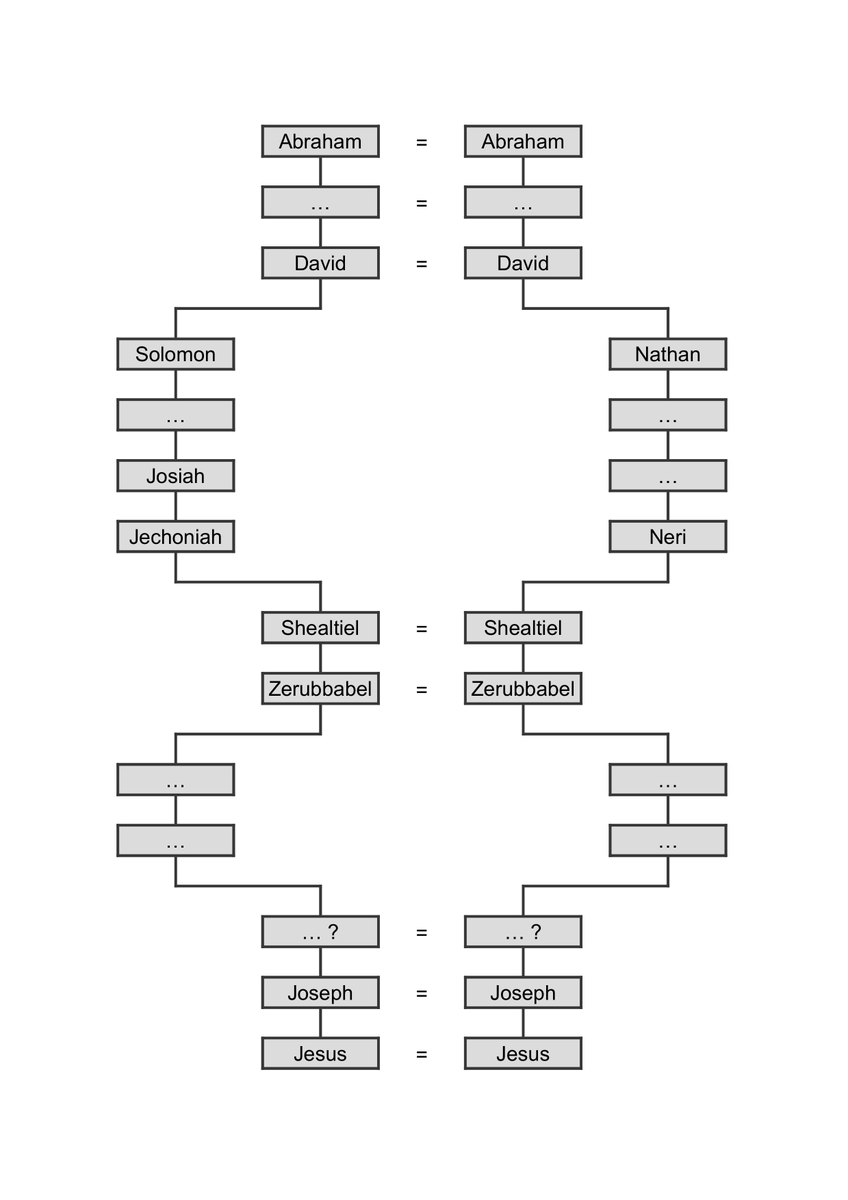

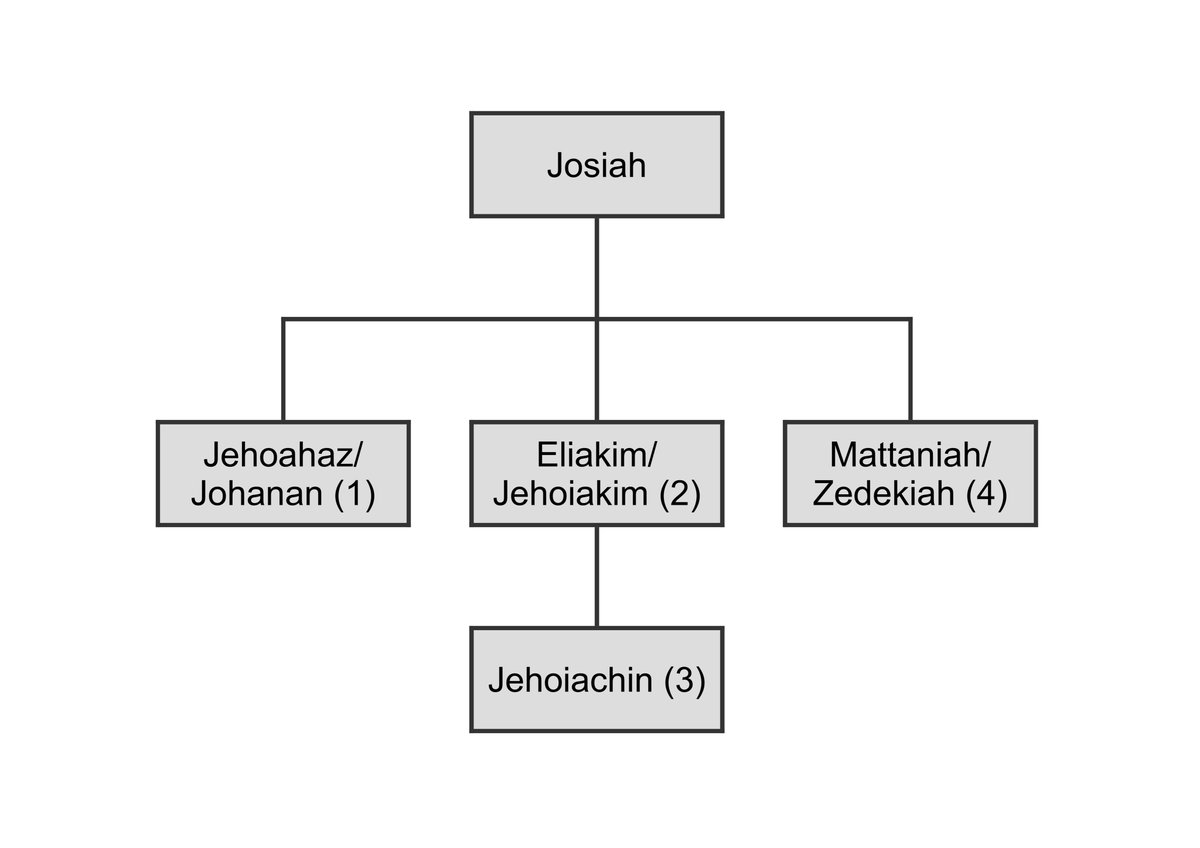

At first, Josiah was succeeded by his son Jehoahaz (2 Chr. 36.1);

then Jehoahaz was replaced by his brother Eliakim (36.4), who was named ‘Jehoiakim’ on his accession to the throne;

and, finally, Jehoiachin was carried away by Nebuchadnezzar and replaced by his uncle Mattaniah, who was named ‘Zedekiah’ on his accession to the throne (2 Kgs. 24.17).

All well and good.

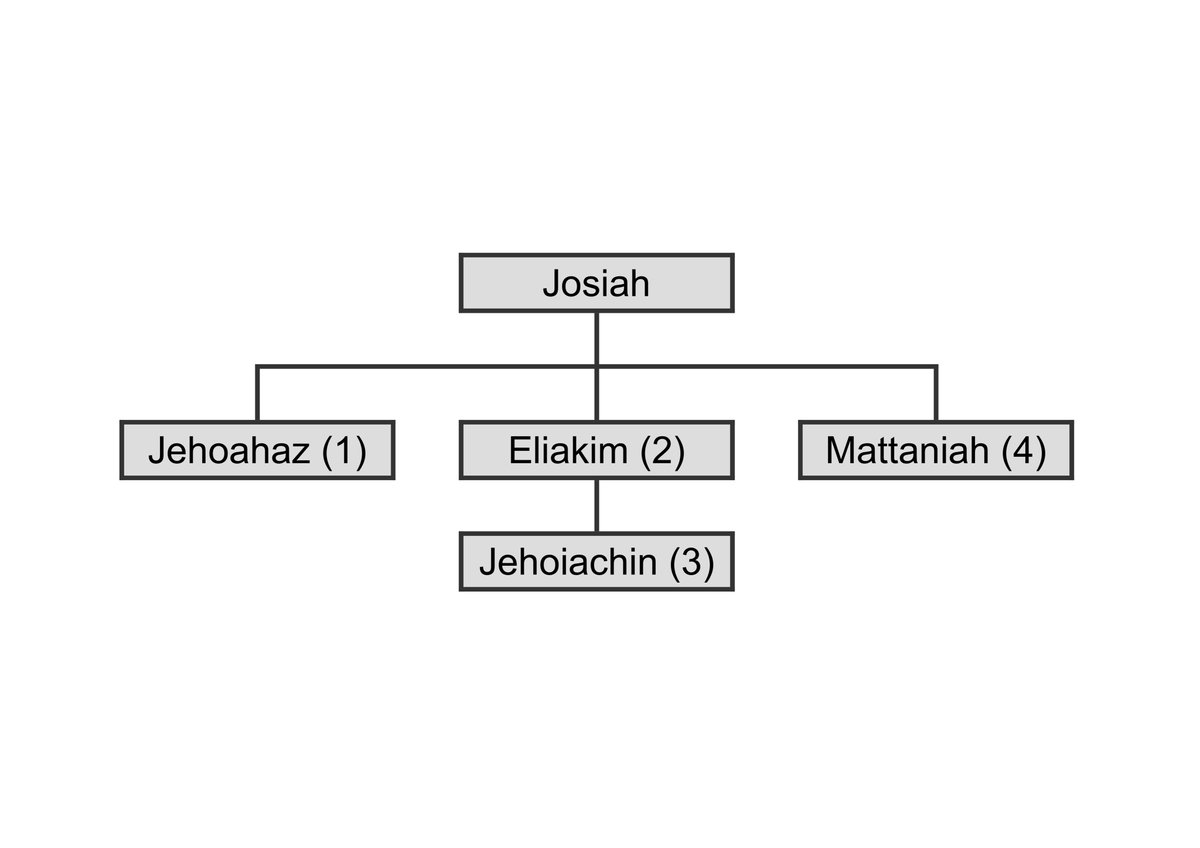

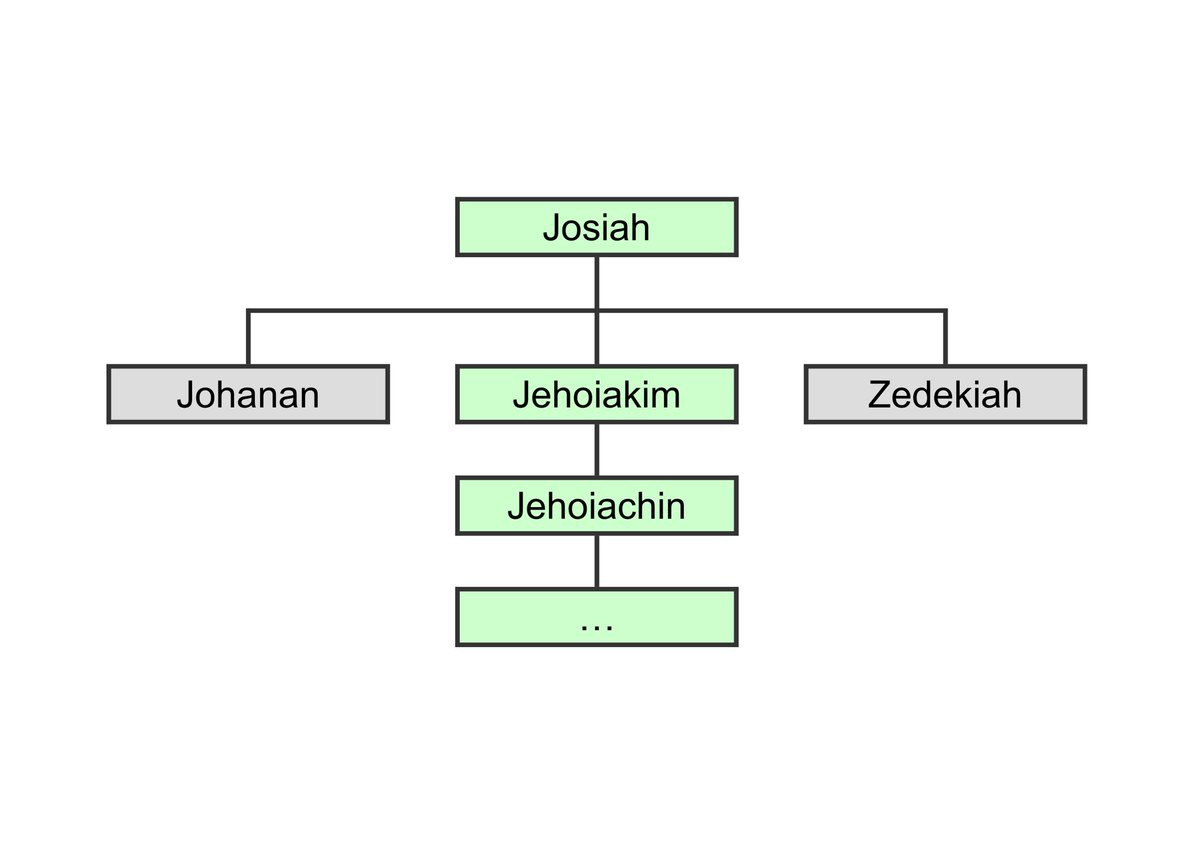

First, who’s Johanan?

That much at least doesn’t seem too hard to figure out.

And, since 1 Chr. 3.15 refers to Johanan as Josiah’s *firstborn* (3.15),

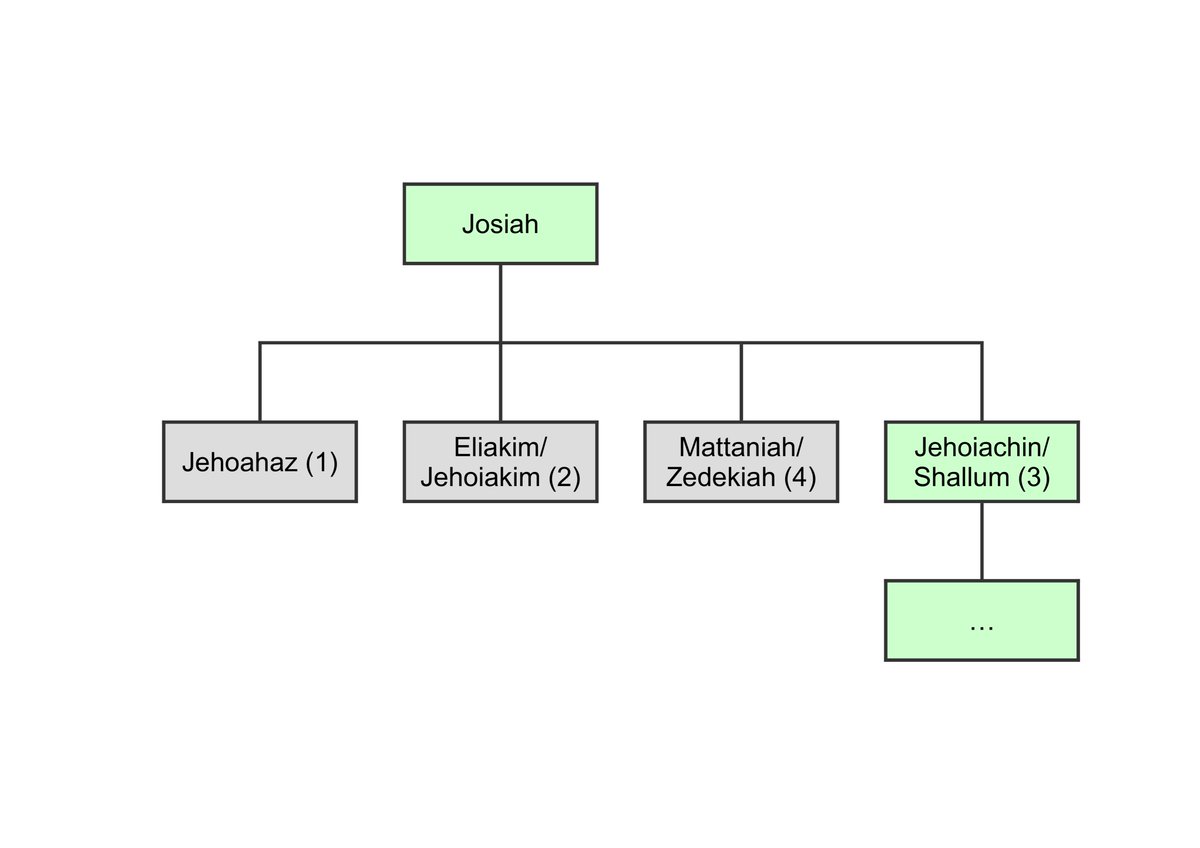

Well, the name ‘Shallum’ isn’t mentioned in the narratives of 2 Kgs. 24–25 or 2 Chr. 36.

It *is*, however, mentioned by Jeremiah,

who refers to Shallum as ‘a son of Josiah’ and as a man who ‘reigned in Josiah’s place’ (Jer. 22.11).

So, who exactly is he?

It’s not immediately obvious.

Let’s therefore make things harder;

🔹 Why does 2 Chr. 36.10 refer to Mattaniah as Jehoiachin’s ‘brother’ when 2 Kgs. 24 refers to him as Jehoiachin’s ‘uncle’?

But, remarkably, they can all be plausibly answered/resolved by the postulation of a single hypothesis:

Hence, like Joseph’s sons (Ephraim and Manasseh), who became brothers and co-heirs alongside the rest of Jacob’s sons,

That hypothesis is then able to explain:

🔹 why 2 Chr. 36 has Jehoiachin accede to the throne at the age of 8 rather than 18,

🔹 why Matthew is able to refer to Josiah as the father of Jehoiachin and his *brothers* (plural).

The man who excised large sections of text from God’s word (Jer. 36.23) was himself excised from the Messianic line/genealogy. God bypassed him.

Note: The occasion of Shallum’s promotion is not clear to me, but the name ‘Shallum’ can plausibly be rendered as ‘He has been compensated’ (cp. שלם in Exod. 22.4–6, JAram. תשלומא = ‘compensation’, etc.).

——————

But we still have a number of other issues to deal with, the most immediate of which is the issue of *Jehoiachin’s* curse.

Jeremiah didn’t just curse Jehoiakim; he also cursed Jehoiakim’s son, Jehoiachin.

As before, Jeremiah’s prophecy raises a number of awkward questions:

And, more importantly, how can Luke have Jesus inherit ‘the throne of David’ (Luke 1.32) when Matthew lists Jesus as a descendant of Jehoiachin?

——————

Despite a wayward start, Jehoiachin appears to have sought (and found) God’s mercy later in life.

Acc. to Jeremiah, the fault of Jehoiakim (Jehoiachin’s father) was twofold. First, he ignored God’s word (22.21).

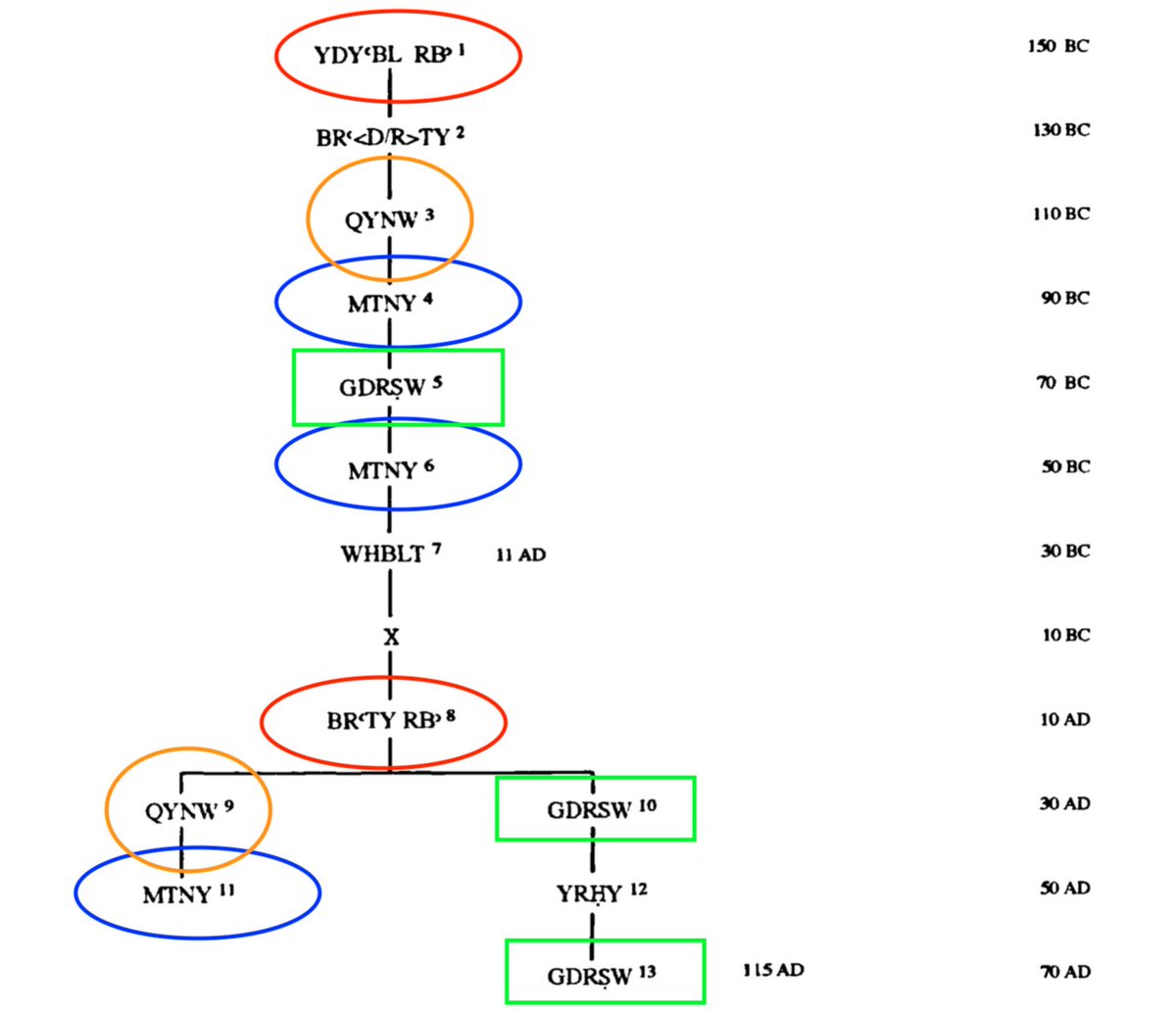

and, in response, Haggai chose to refer to his (great-grand)son Zerubbabel in distcintly Jeremianic terms, i.e., as a ‘signet ring’ on God’s hand (Hag. 2.23).

Remarkably, they are all consistent with a relatively simple and, given our discussion of Jehoiachin’s promotion, non-contrived hypothesis, which is able to answer the various questions outlined above.

And yet, by means of Shealtiel’s adoption, God was able to raise up the Messiah from Judah’s royal line.

🔹 a journey to/from Babylon,

🔹 a mention of ‘a leader and his brothers’—a phrase only found in vv. 2 and 11,

while Luke provides us with Shealtiel’s *biological* genealogy.

Matthew wants to draw our attention to Shealtiel’s connection with Judah’s royal line—a line which is well documented elsewhere and needn’t be reproduced in full in Matt. 1—,

(Acc. to Luke, Shealtiel is the 21st generation from David, which seems about right since Shealtiel and David are separated by c. 450 years.)

but, before we leap to such conclusions, we should consider the historical context of Matthew and Luke’s genealogies.

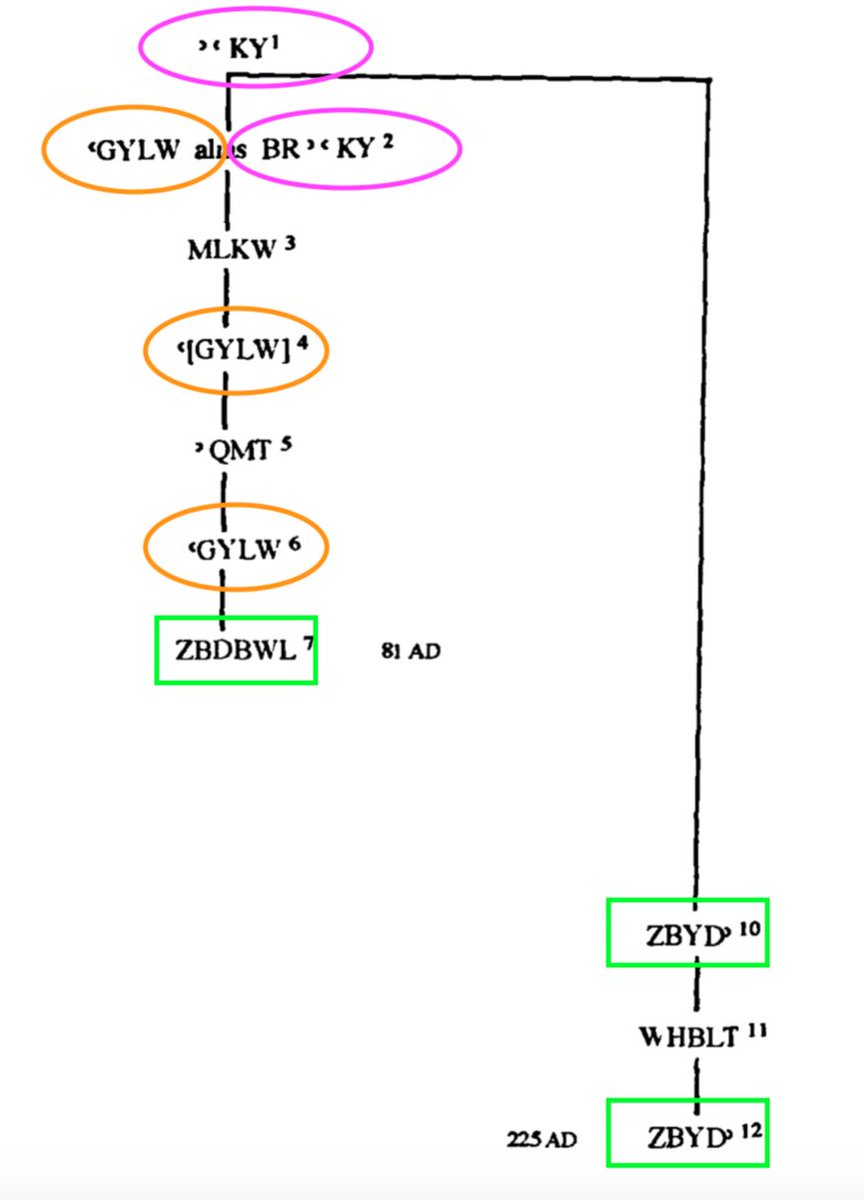

Men were required to perpetuate their name/lineage by whatever means they could.

Sheshan, for instance, didn’t have any sons, so he gave his daughter to his servant (Jarha),

And Abraham intended to pursue a similar course of action with his servant Eliezer (cp. Gen. 15.2–3).

As a result, names/lineages frequently became endangered, which is why the duty of ‘yibbum’ (Levirate marriage) was enshrined in Mosaic law.

Consequently, we shouldn’t be surprised to find messy genealogies in Scripture,

And, as we’ll now discover, Jesus’ genealogy is equally messy between Zerubbabel and Joseph.

Briefly put, I don’t know.

But then there’s little reason why I should.

which allows us to suggest why Matthew’s and Luke’s genealogies differ from one another (between David and Shealtiel).

Why Matthew and Luke differ therefore remains unknown (for now).

In Luke, Joseph doesn’t seem to be very well connected with the house of David.

Wasn’t Joseph known to be a descendant of David?

Had his past been forgotten about for some reason?

It appears to have been a common practice in Jesus’ day for parents to reuse/reinvent the names of their ancestors.

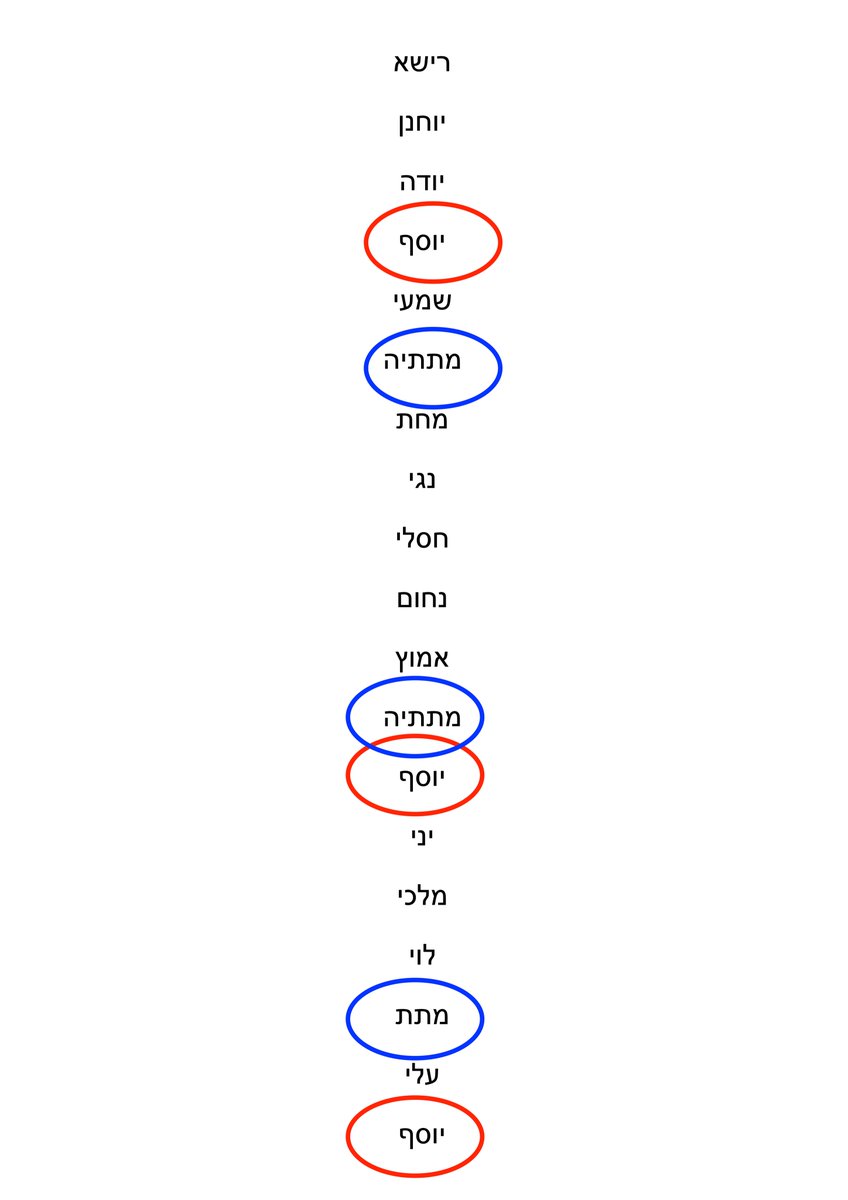

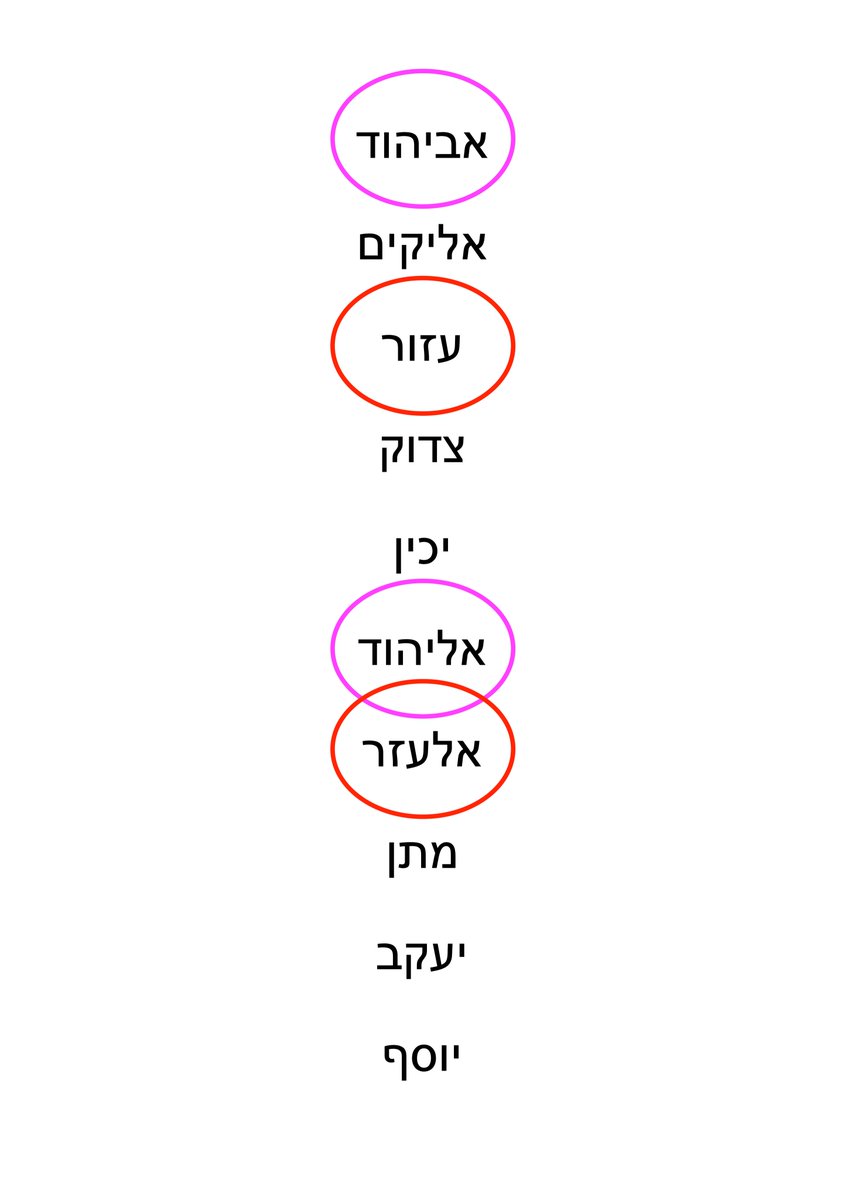

Consider the names recorded by Matthew (in the final leg of his genealogy).

As can be seen, the element הוד occurs in both the names אביהוד and אליהוד (which are separated by 5 generations),

and the root עזר occurs in both עזור and אלעזר (which are separated by 4 generations).

Two of these names are a very good fit with Luke’s genealogy.

The name יוסף is attested in generations 1, 6, & 15.

And the element מתת is attested in generations 3, 8, & 14.

The name יעקב is patriarchal, and hence resonates with יוסף and לוי and יהודה.

The name יוסי is a shortened form of יוסף.

The name שמעון is related to שמעי.

By contrast, the last three names in *Matthew’s* genealogy do not share any notable elements/features with the rest of Matthew’s names, nor do the names of Jesus’ brothers.

which means we can schematise the relationship between Matthew’s and Luke’s genealogies in one of two ways.

which could (as before) explain why Luke’s genealogy is the longer of the two.

Matthew’s and Luke’s genealogies exhibit a superficial tension, but are underlain by plausible principles and patterns.

but they are nonetheless plausible accounts of history.

Shealtiel is grafted into Jehoiachin’s line in order to redeem Jehoiachin from God’s curse;

THE END.

Please Re-Tweet if you’ve found it helpful.