Long after its ban in 1829, Sati remains in public discourse by virtue of being a polemical weapon

"Oh...what about Sati? Was that not also a tradition. Did we not get rid of that?"

Very recently the commentator @sardesairajdeep used Sati as a polemical weapon while arguing in favor of changing the rules of admission at the Keralite shrine of Sabarimala

It is used as a polemical tool by both Western liberals as well as conservatives albeit with different lenses

For others of a more religious disposition, it is a stick to critique Indian religion, and make a case for the superior "Christian" civilization

This is despite the fact that Sati for the most part was a voluntary act

Here's what he said -

(Contd..)

To be perfectly honest, Mansfield's questions are valid.

Among Indian progressives / liberals, the responses have tended to border on self flagellation

Response 1

"Oh...Sati was an incredibly rare practice, exaggerated by missionaries and dishonest East India officials"

"Oh. Sati was non-existent in Ancient India. It is a medieval practice that arose in reaction to Muslim depredations among certain royal houses"

Firstly there is a tendency to conflate the medieval practice of Jauhar in north west India with Sati, which predates it by many centuries

"Oh...ours was an evil religion We used to burn widows...We must thank Mr Bentinck and Mr Roy for reforming us"

It is oblivious to the numerous critiques of Sati within the Hindu establishment for much of the past 1500 years

There are some exceptions like the early 20th cen scholar Anant Sadashiv Altekar, whose work - "The Position of Women in Hindu civilization" published in 1938, remains a classic and worth reading to understand Sati, among other things

While I have referred some primary sources, many of the pointers are taken from Anant Altekar's fine aforementioned work

It is quite likely that the practice was more prevalent among the warrior class and arose from the belief possibly that the departed may require all their "possessions" in the next life

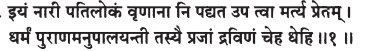

इमा नारीरविधवाः सुपत्नीराञ्जनेन सर्पिषा संविशन्तु

अनश्रवो.अनमीवाः सुरत्ना आ रोहन्तु जनयोयोनिमग्रे

उदीर्ष्व नार्यभि जीवलोकं गतासुमेतमुप शेष एहि

हस्तग्राभस्य दिधिषोस्तवेदं पत्युर्जनित्वमभि सम्बभूथ

"Let these unwidowed dames with noble husbands adorn themselves with fragrant balm and unguent. Decked with fair jewels, tearless, free from sorrow, first let the dames go up to where he lieth"

(Contd..)

So clearly there is no encouragement to the woman to ascend the funeral pyre here

"O Dead man. This lady who cares for your lineage to continue, is practicing her Swadharma, and is now going to come near you. But let her in future have kids, grandkids, and prosperity"

Even the later layers of Vedic literature like the Brahmanas and Upanishads do not mention Sati or anything even approaching it

“After the wife lies beside the corpse at the funeral, her brother-in-law, being a representative of her husband, or a pupil of her husband, or an aged servant, should cause her to rise from that place with "Arise, O wife, to the world of life“

This shows the consistency of thought at work over a very long period of time.

And Asvalayana Grihya Sutra is a much later text probably belonging to 600-700 BC

Yet you see a verse in the latter referencing the former, to drive home the same positive point

“On returning from the funeral pyre, the widow brings back with her the husband’s instruments like bow, jewels, etc. We hope the widow and her relatives can lead a prosperous life”

Here's Manu on Niyoga

He first describes Niyoga but also condemns it, which suggests that even in his time, the practice was not totally extinct

प्रजेप्सिताऽऽधिगन्तव्या सन्तानस्य परिक्षये ॥ ५९ ॥

Ganganatha Jha translation

"On failure of issue, the woman, on being authorised, may obtain, the desired offspring, either from her younger brother-in-law or a ‘Sapiṇḍa’

एकमुत्पादयेत् पुत्रं न द्वितीयं कथं चन ॥ ६० ॥

"He who has been authorised in regard to a widow shall, annointed with clarified butter and with speech controlled, beget, at night, one son,—and on no account a second one"

"विधवायां नियोगार्थे निर्वृत्ते तु यथाविधि

गुरुवत्च स्नुषावत्च वर्तेयातां परस्परम्

"When the purpose of the ‘authorisation’ in regard to the widow has been accomplished, the two should behave towards each other like an elder and a daughter-in-law" (!!)

ततः प्रभृति यो मोहात् प्रमीतपतिकां स्त्रियम्

नियोजयत्यपत्यार्थं तं विगर्हन्ति साधवः

"Whenever any one, through folly, ‘authorises’ a woman whose husband is dead, to beget children,—him the good men censure"

It clearly suggests that the whole idea of widow self immolation would have been anathema in a society that was worldly enough to explore Niyoga to keep the lineage alive

In Ramayana, there is one case of Sati in Uttara Kanda, but not in the main epic.

In Mahabharata we have the famous case of Pandu's second wife Madri who becomes a Sati

But Madri is adamant as she regards herself as responsible for Pandu's death and is suffused with guilt

So it is perhaps closer to a guilt-driven suicide than a case of Sati

Even in Mahabharata, there is no other widow who undertakes Sati, though this is a story of warrior widows.

Not the wives of Abhimanyu, Kauravas. None

Most famously we have the instance of Vichitravirya's wives - Ambika and Ambalika (and their maid), bearing sons through Veda Vyasa, who was Vichitravirya's half brother

And without a single justification or argument in its favor in the very vast corpus of Vedic literature AND Dharma texts

But what is the earliest historical occurrence of Sati that we know of?

Keteus had 2 wives. As with Pandu's wives, both of Keteus' wives were eager to die but the younger one got her wish

Post this instance, we don't get to hear about Sati for a long while except for the Madri exception in the Epic

Ideals of asceticism have become increasingly popular in society, and this is reflecting in the literature of the time

Most notably Bhasa, Vatsyayana, Kalidasa and even Shudraka

In Bhasa's adaptations of MB episodes, we see the wives of Abhimanyu, Duryodhana and Jayadratha committing Sati.

Not in Mahabharata

She commits Sati even before her husband's death (Harsha's father) as there is no chance of his recovery from poor health (Source - Altekar)

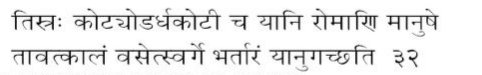

Most notably Vishnu Smriti, and Parashara Smriti - two v late Dharma texts of the second half of the 1st millennium CE

"If a woman follows her departed lord, by burning on the same pyre, she will dwell in heaven for as many years as there are hairs on the human frame- which will reach the number of 3 crores and a half"

Practices like Niyoga are now clearly a thing of the very ancient past. While the reform on that front was perhaps desirable, there was overcompensation in the other direction

Nevertheless it was still extremely rare. And hardly obligatory

So it did not result in any major increase in the incidence of Sati. Actual occurrences remained extremely rare and practically unheard of throughout 1st millennium

And his writings show that this inclination towards Sati among some Smriti writers was vociferously opposed by others like himself

"As in the case of men, even for women suicide is forbidden. As for what Aṅgiras has said—‘they should die after their husband’,—this also is not an obligatory act, and so it is not that it must be done

"To die after one's beloved is most fruitless. It is a custom followed by the foolish. It is a mistake committed under infatuation. It is a mistake of stupendous magnitude"

(Source : Altekar)

The Woman is the embodiment of the supreme goddess and if a person burnt her with her husband, he is condemned to eternal hell

(Source: Mahanirvana Tantra - from Altekar)

It remained rare everywhere else. Infact the oldest Sati stone in Rajputana dates only to 838AD

Most notably the Kings Kalasha and Utkarsha were followed in death by their wives as well as concubines

An intriguing strategem.

Sati cases are also common in the 11th cen work Kathasaritasagara - possibly written in Kashmir

But it remained barred for brahmins

(source - Altekar)

So even as late as 15th century, it was primarily a Kshatriya practice

But even in Deccan we see inroads happening in the middle of 2nd millennium

1100-1400 - 11 cases

1400-1600 - 41 cases

Source - Epigraphia Carnatica (through Altekar)

When Ajit Singh of Marwar died in 1724, 64 women mounted the pyre

However when Shivaji died, just one of his wives became a Sati

There is an 11th cen inscription in Karnataka that tells of a lady named Dekabbe who would not listen to her parents and insisted on mounting the pyre

Though he also speculates that the % was way higher among Rajput rulers (possibly 25% in his words)

Firstly the high concentration of numbers in Bengal - a region not hitherto associated with Sati ( a point remarked by Meenakshi Jain among others).

Second the v wide prevalence among Bengali Brahmins

However we see a change in the EIC years.

Calcutta - 5099

Dacca - 610

Murshidabad - 260

Patna - 709

Bareilly - 193

Benares - 1165

Not because one doesn't trust EIC - that would be a tribalist attitude of not trusting the foreigner

But because the patterns are historically anomalous. Why Calcutta? And why had it picked up so much among brahmins?

In fact many Indian rulers had already taken measures against Sati before Bentinck's ban

But these were anomalous reactions without serious popular backing

While Sati is very much a thing of the very distant past, and was always a marginal practice, nevertheless studying its history teaches us a lot about Indian intellectual history more generally!

AS Altekar's Position of Women in Hindu civilziation

Rig Veda translation- Ralph Griffith translation

Atharva Veda Samhita translation : Ram Sharma Acharya

Manu Smrti - Ganganath Jha