What would be a good choice for the number 10?

We don't need to be Sherlock Holmes to get this. Naturally, all humans share the same number of fingers. But it is not that easy.

We need to close the fingers into a "fist". "Pañcha" पञ्च in Sanskrit comes from that. The similarity can be seen in Persian panjā, English punch etc.

Now we see a peculiar problem with the words for numbers. The original word that was used in that meaning goes down in popularity, due to potential for confusion with the number.

This is because the word "first" doesn't follow the meaning of "alone" anymore. There are multiple objects and this is the "important" one (Latin "primi" Sanskrit "pramukha").

The Sanskrit suffix "ta" त denotes "that which has the property of".

In Arabic, "setta" and "saba" ("ba" and "pa" are equivalent in Arabic).

In Egyptian, "sjsw" and "sfhw".

In Sumerian, 6 "as" and 7 "umin" (5+2).

languagesgulper.com/eng/Sumerian_l…

The 7 heavenly bodies are the rulers that define the calendar. They are the "Sapta Graha" in Sanskrit.

I suspect the word "aha" (day) followed the Egyptian version of numbers.

In Telugu, the word "Elu" ఏలు means "to rule". "Ēlika" is a synonym for "Pālaka".

pragyata.com/mag/the-infini…

What is this new thing about 9? Well after you fold 4 times (you get 8), you need a new cloth, or a new block of clay.

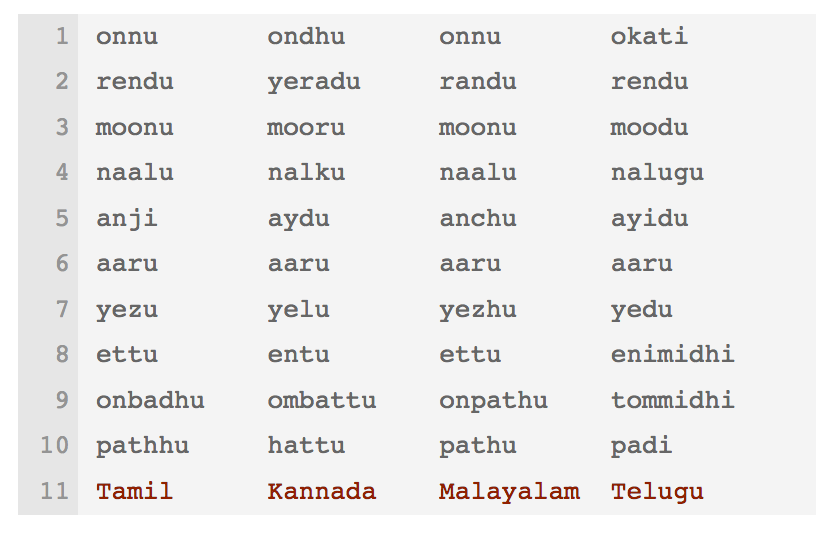

The word is "onbadu" ఒంబదు, which is "on+padu", coming from the words for 1 and 10. It is literally 1 subtracted from 10.

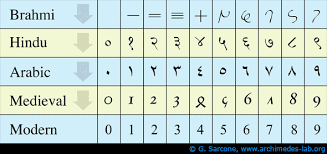

However, I have a theory. The word 4 is related to folding (like for 8). We can also see that in the Brahmi sign for 4.

"Śam nō Mitraḥ Śam Varunaḥ"

May Mitra and Varuṇa lead us to auspiciousness (and lots of 100s). 😃

(End of thread).

Equally possible. 😀