Today’s Left has begun to embrace FDR’s court-packing plan in the 1930s, but in some ways, the antislavery struggle of the 1850s represented an even more sweeping assault on the foundations of judicial power.

Abolitionists and Republicans condemned the Dred Scott decision, “this judicial incarnation of wolfishness,” as Frederick Douglass called it. Yet they knew the problem of proslavery jurisprudence could not be solved by antislavery jurisprudence alone. rbscp.lib.rochester.edu/4399

“We can appeal from this hell black judgment of the Supreme Court,” said Douglass, “to the court of common sense and common humanity.” The remedy for Dred Scott did not reside in a lawyer’s plea or a judge’s opinion, but in mass political struggle.

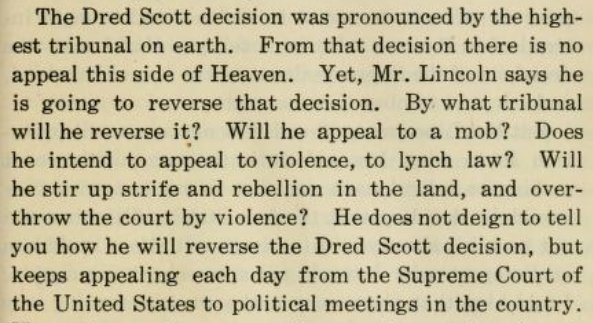

For the Republican Party, that struggle meant declaring political war on the idea of an all-powerful judiciary. After 1857 Republicans responded to Dred Scott, as the historian David Potter wrote, not with “an attack on the decision,” but “an attack on the Court.”

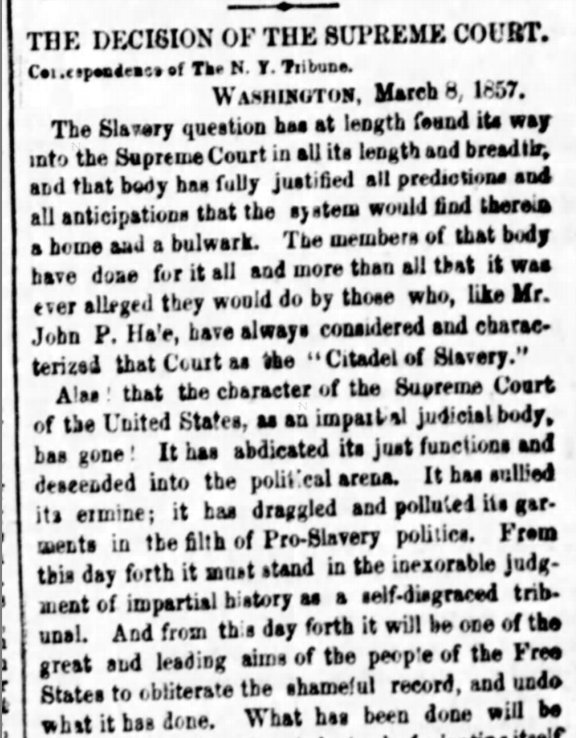

Some suggested immediate reforms, including the appointment of up to five new justices. “This Court is the citadel of Slavery,” reported one Cincinnati newspaper, “and Republicans intend to storm it.”

Probably the most popular idea — maybe even more radical, in its way, than court-packing — was a plan “reorganize” the entire federal judiciary on the basis of circuit court population.

Ultimately, the most important Republican response was not any of the various technical reform proposals, but a concentrated *political* attack on the Court’s authority as an elevated and impartial arbiter of law.

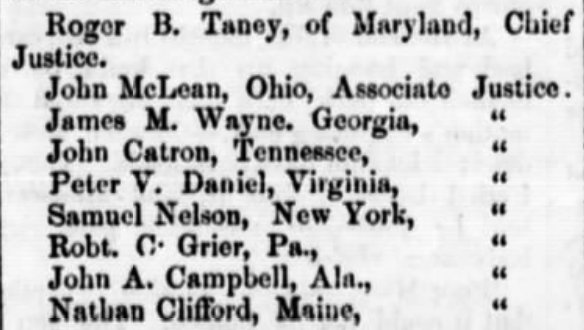

Famously, both Seward and Abraham Lincoln accused the Court of advancing a proslavery conspiracy: Chief Justice Taney had plotted with President Buchanan to craft a piece of legal “machinery” that would make slavery lawful everywhere. abrahamlincolnonline.org/lincoln/speech…

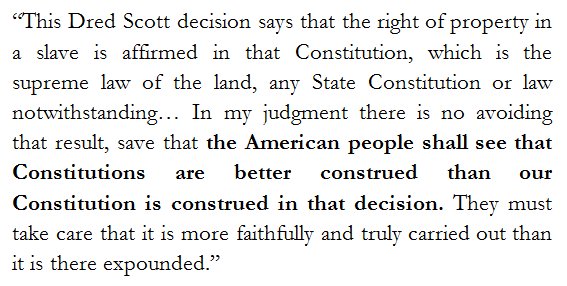

Above all, the Republican assault struck at the fundamental power of the judiciary. The Supreme Court, they argued, had the authority to decide particular cases, but not to settle larger political disputes over the meaning of the Constitution.

Today we call this power “judicial review,” but as scholars like Keith Whittington argue, it really amounts to something much more like to “judicial supremacy,” and its roots are not legal or constitutional but themselves political. press.princeton.edu/titles/8427.ht…

After Dred Scott, Republicans mounted a direct challenge to this power — perhaps the most aggressive popular attack on judicial supremacy in U.S. history. “A Court makes a decision,” argued one New York legislator, “but does not make the law.”

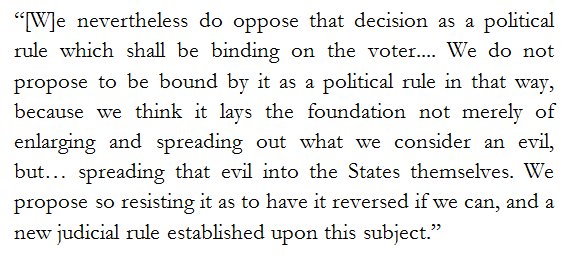

Yet Lincoln persisted in rejecting judicial supremacy — and also the basic idea underlying it, that law somehow exists before or beyond politics, and thus it was illegitimate to resist the proslavery Court through popular antislavery mobilization. quod.lib.umich.edu/l/lincoln/linc…

Across the late 1850s, Lincoln argued that “the American people,” not the Supreme Court, were the true arbiters of the Constitution, and that the only way to defeat the proslavery judiciary was through mass political struggle.

quod.lib.umich.edu/l/lincoln/linc…

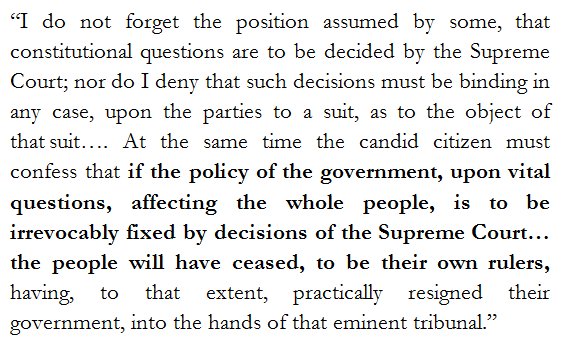

After Lincoln and Hamlin were elected in 1860, the new president’s inaugural address articulated this view in perhaps the strongest language he ever used.

quod.lib.umich.edu/l/lincoln/linc…

Once in power, Lincoln and congressional Republicans “reorganized” the federal judiciary and “packed” the Court, adding an additional justice in 1863. More fundamentally, though, they simply ignored the proslavery precedents established in the 1850s.

In June 1862, for instance, Congress passed and Lincoln signed a bill banning slavery from the federal territories—a direct violation of the ruling in Dred Scott. The Court meekly acquiesced, recognizing that its political power was long since broken.

cwemancipation.wordpress.com/2012/06/19/sla…

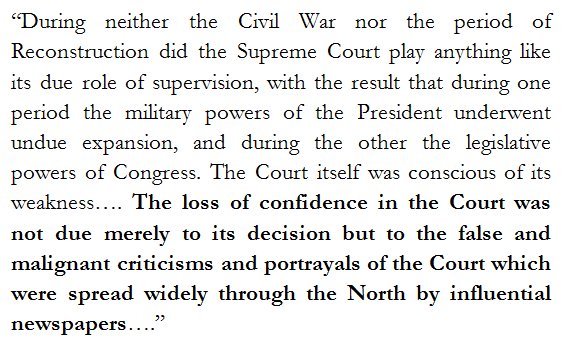

As the legal historian Charles Warren later lamented, Republicans' popular assault on the Court crippled the institution for more than a decade. pulitzer.org/winners/charle…

(For me, this was Good: it helped make emancipation and Reconstruction possible.)

Drawing direct “lessons from history” is a fool’s errand, but at least this should remind us that judicial power — however grandly it may be imagined by friends and foes alike — is critically dependent on political currents.

In some ways, the Left today shares the position of antislavery forces in the 1850s: a rich, well-organized sect, whose commitment to property far exceeds its belief in democracy, has made the Supreme Court a citadel of reaction: thenation.com/article/the-bo… cc @JedediahSPurdy

Yet as Keith Whittington argues, the resort to judicial supremacy is not a sign of strength, but an admission of weakness: a beleaguered regime calls upon the authority of the Court only to achieve what it cannot accomplish through electoral politics.

The Bosses’ Constitution has no more chance of winning public support today than the slaveholders’ agenda of the 1850s. It is, probably, the *least popular* wing of a larger conservative politics that has come to depend on minority rule: slate.com/news-and-polit… cc @jbouie

To make this undemocratic project vulnerable, it must be made visible.

It may not be enough to question the decisions, the justices, or even the structure of the current Court — we may need to challenge, as Lincoln did, the foundation of its power to determine the law.