Why do we administer potassium to a goal of ≥4.0 mEq/L?

As an intern, potassium (oral or IV) was likely my most common order. How did this become a key part of inpatient providers' days?

Let's have a look at potassium and find out why we "replete".

How do you typically handle potassium in your hospitalized patients?

More specifically, what would you do for a [K+] of 3.4 mEq/L

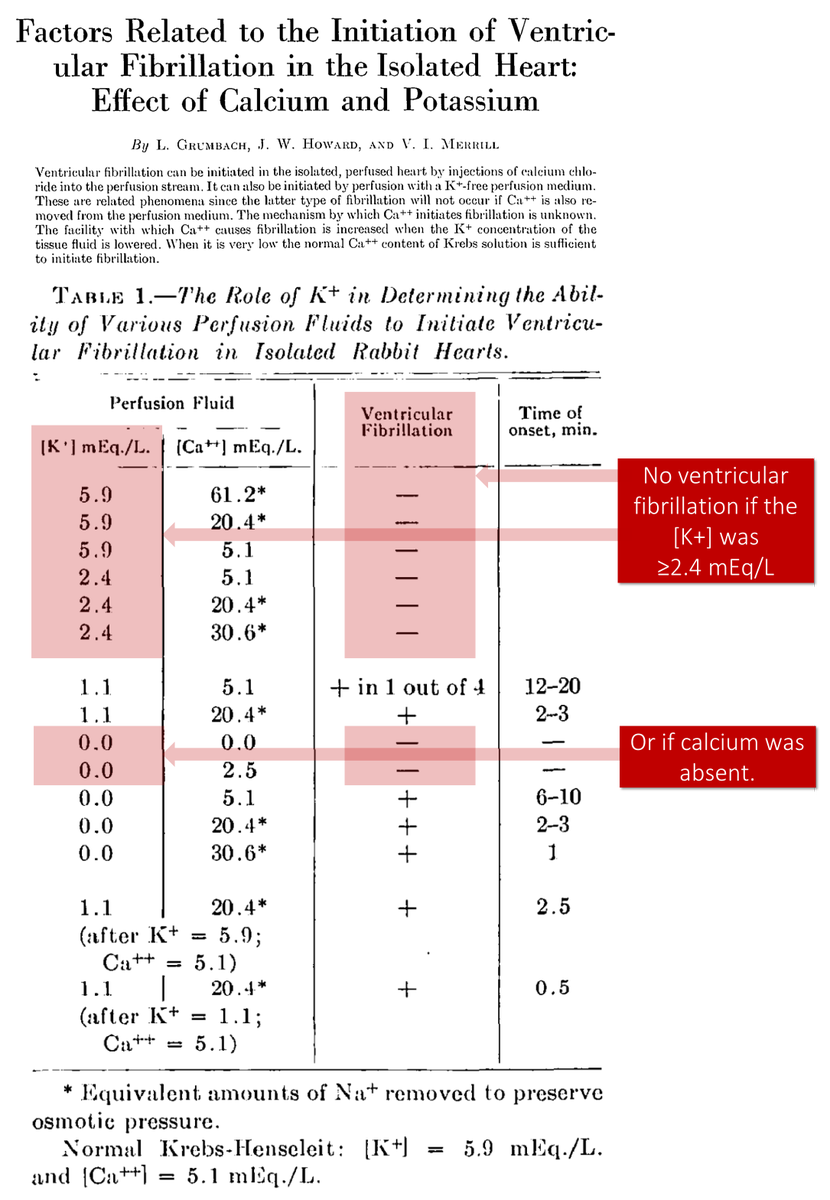

The story of potassium repletion likely began in 1954 when Grumbach et al observed that infusion of low-potassium fluid caused ventricular fibrillation in rabbit hearts.

But, this was NOT seen if the [K+] was ≥2.4 mEq/L or if calcium was absent.

ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/13190630

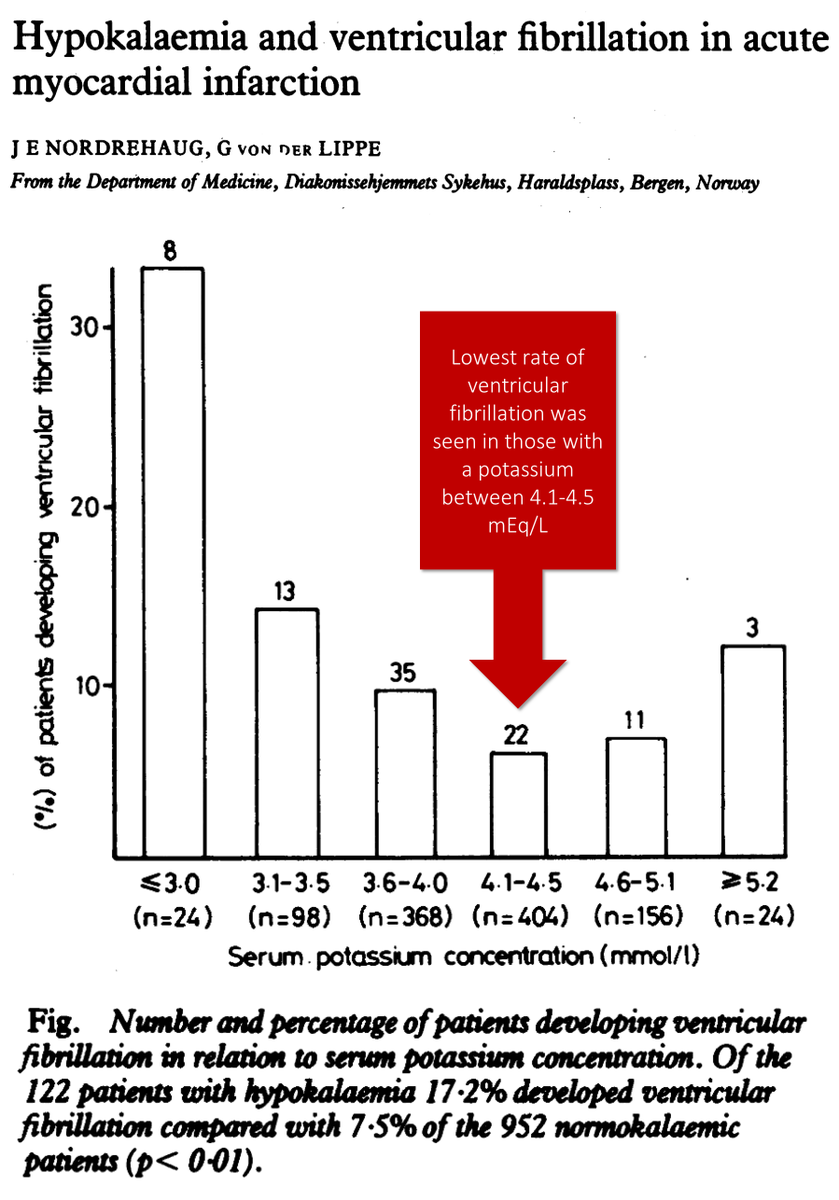

Over the next few decades, observational studies showed that in patients with acute myocardial infarction (AMI), a potassium <4 mEq/L was associated with ventricular arrhythmias (i.e., VT/VF).

ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6651995

There are at least two explanations for the observation that hypokalemia is associated with VT/VF.

a. hypokalemia causes VT/VF

b. hypokalemia is an epiphenomenon, occurring alongside VT/VF in patients with AMI

Which do you think it is?

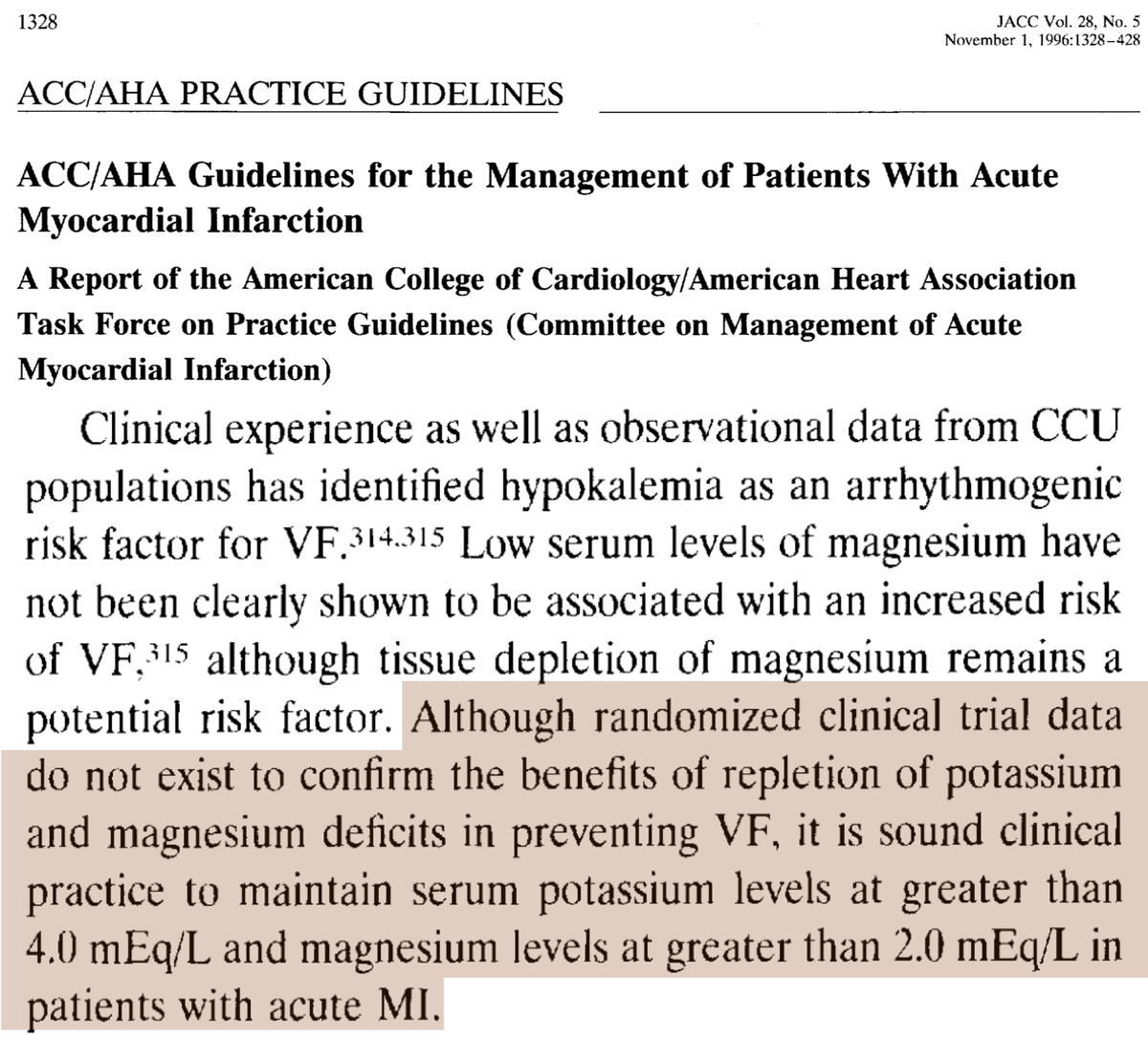

Because we don't have RCT data supporting or refuting the benefit of repleting patients with AMI to a particular value, early guidelines generally erred on the side of caution and suggested we keep patients above 4.

This is an example from 1996.

ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8890834

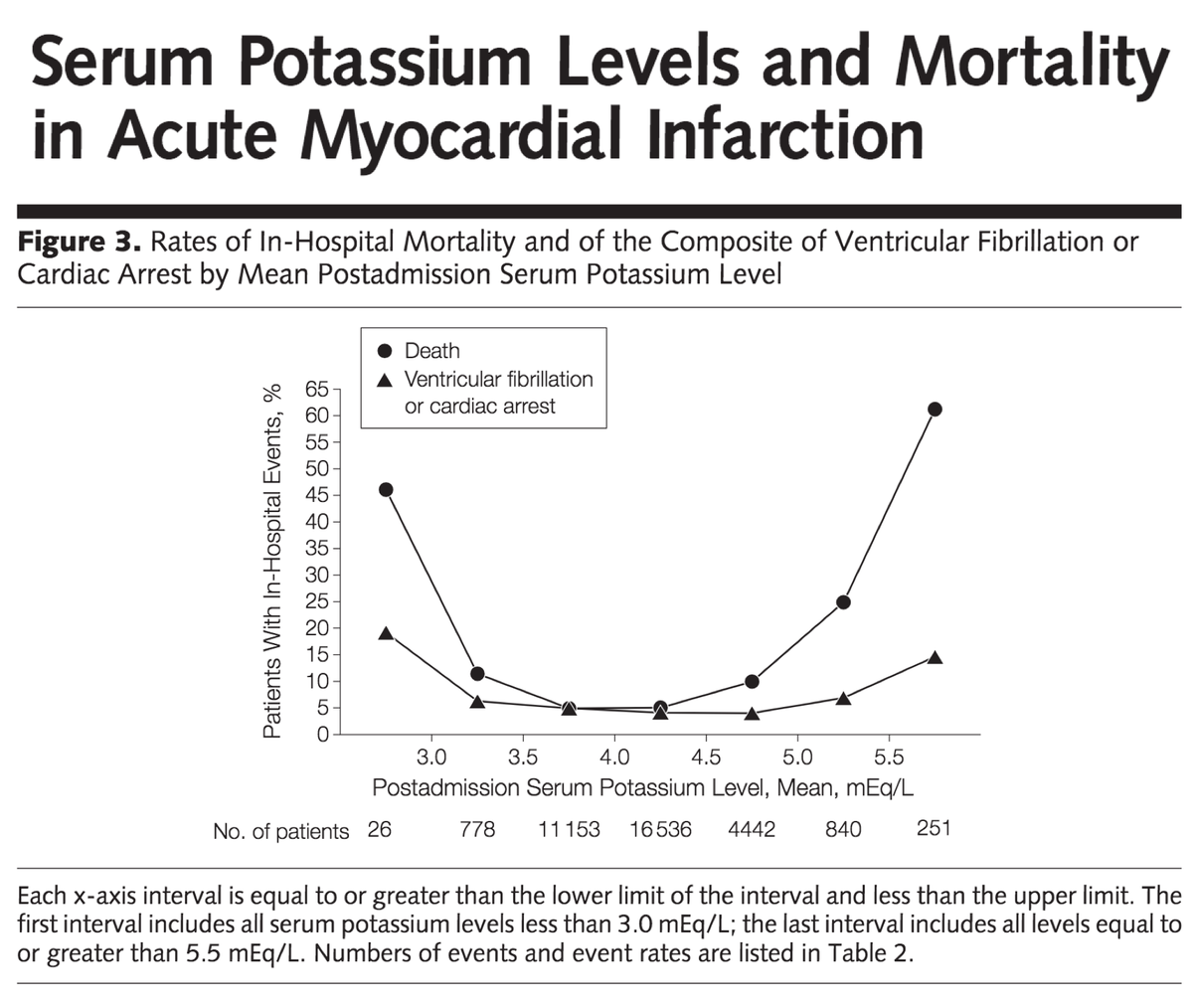

More contemporary data suggests that the "sweet spot" for potassium in AMI may include lower values:

Risk of death is lowest between 3.5-4.5 mEq/L.

Risk of VF is lowest between 3.0-5.0 mEq/L.

ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22235086

The discussion thus far has focussed on patients with AMI. The correlation between potassium and outcomes is clear here and in other cardiac diagnoses (e.g., heart failure and hypertension).

Other conditions (e.g., cirrhosis) may warrant potassium repletion as well.

But...

...many of us are administering potassium to get most of our patients above 4.

I suspect that this is an example of indication creep. We expanded our practice for AMI to other populations, without realizing that their risk of VT/VF is so low that the practice adds no value.

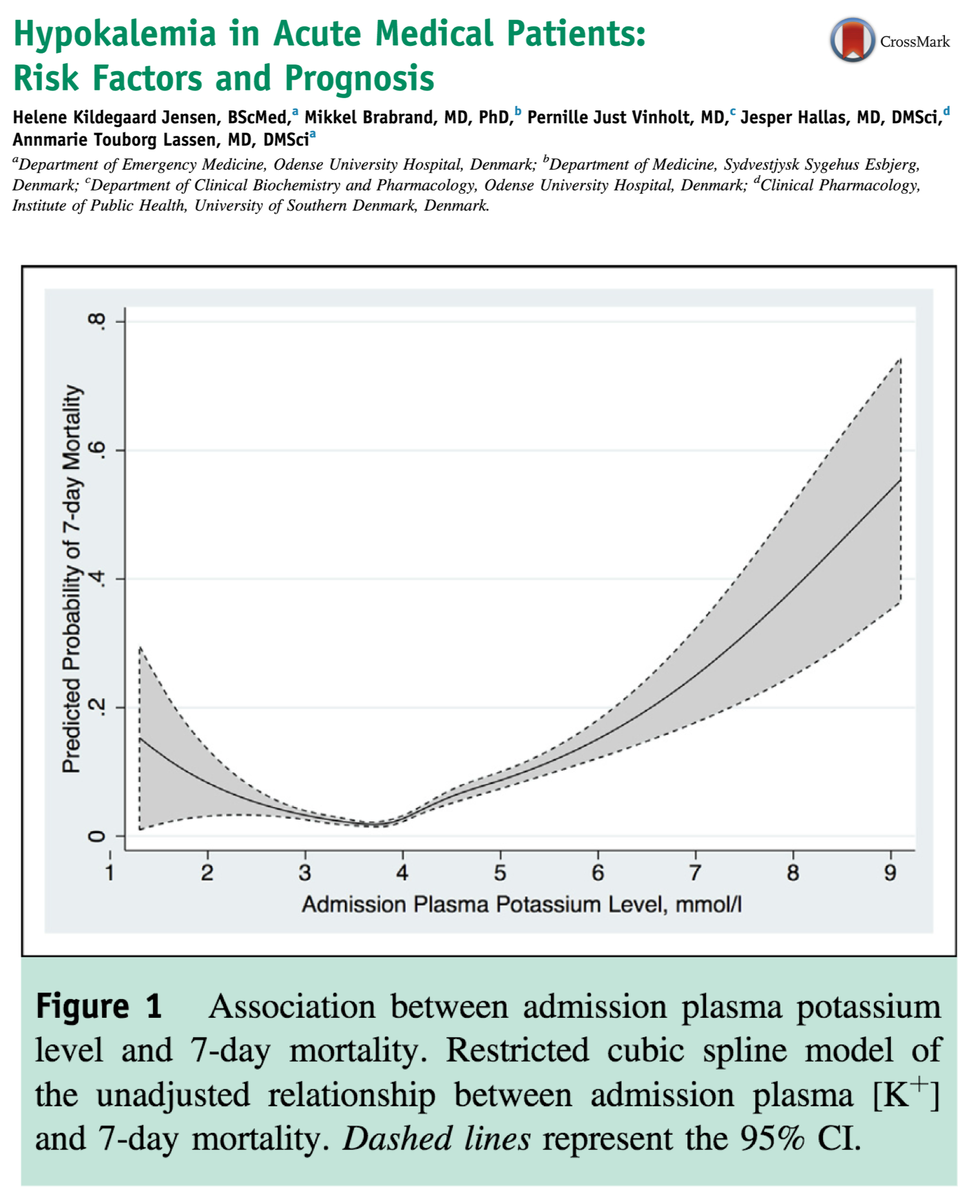

In fact, in acute medical patients, mortality doesn't increase until the admission [K+] is below 2.9 mEq/L.

As with AMI, it's not clear whether hypokalemia is a marker of disease severity or a cause of death.

ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25107385

Based on what's been covered thus far, does anyone plan to alter their practice?

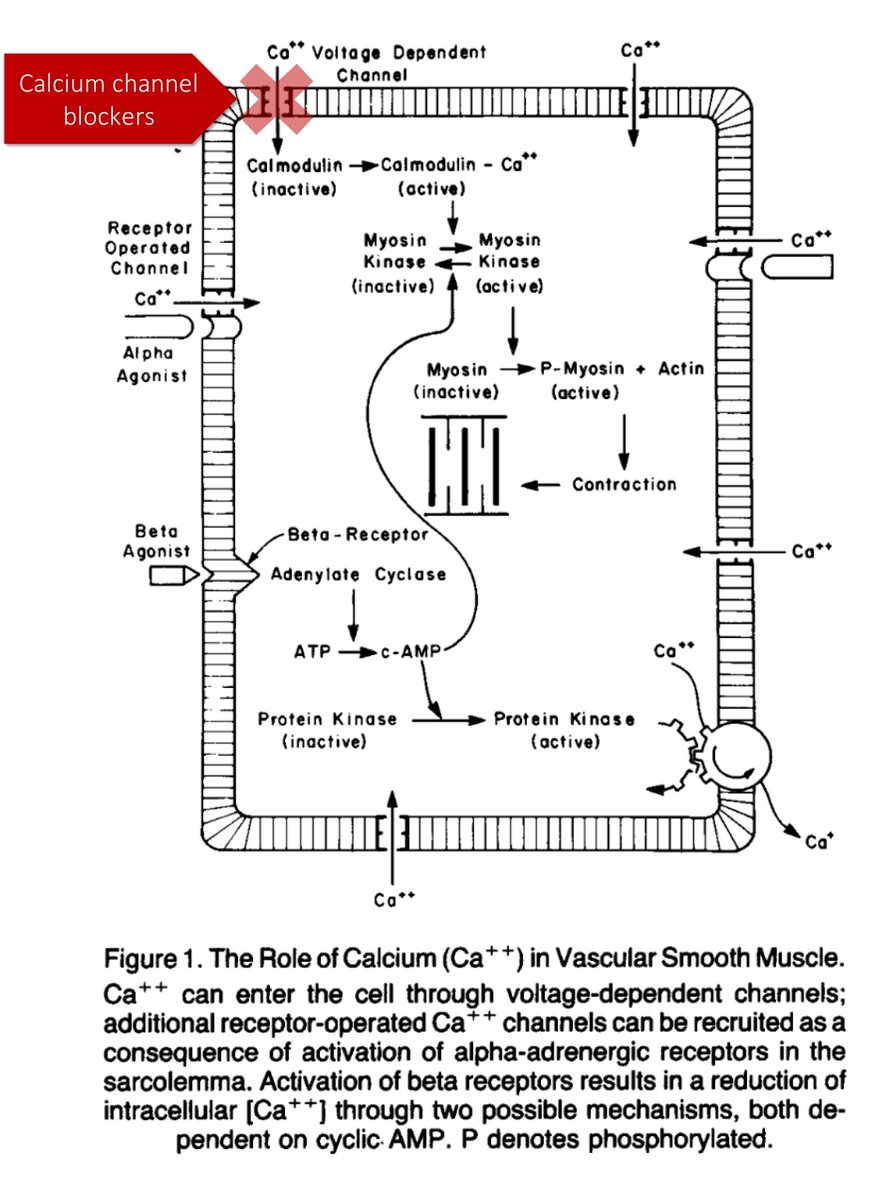

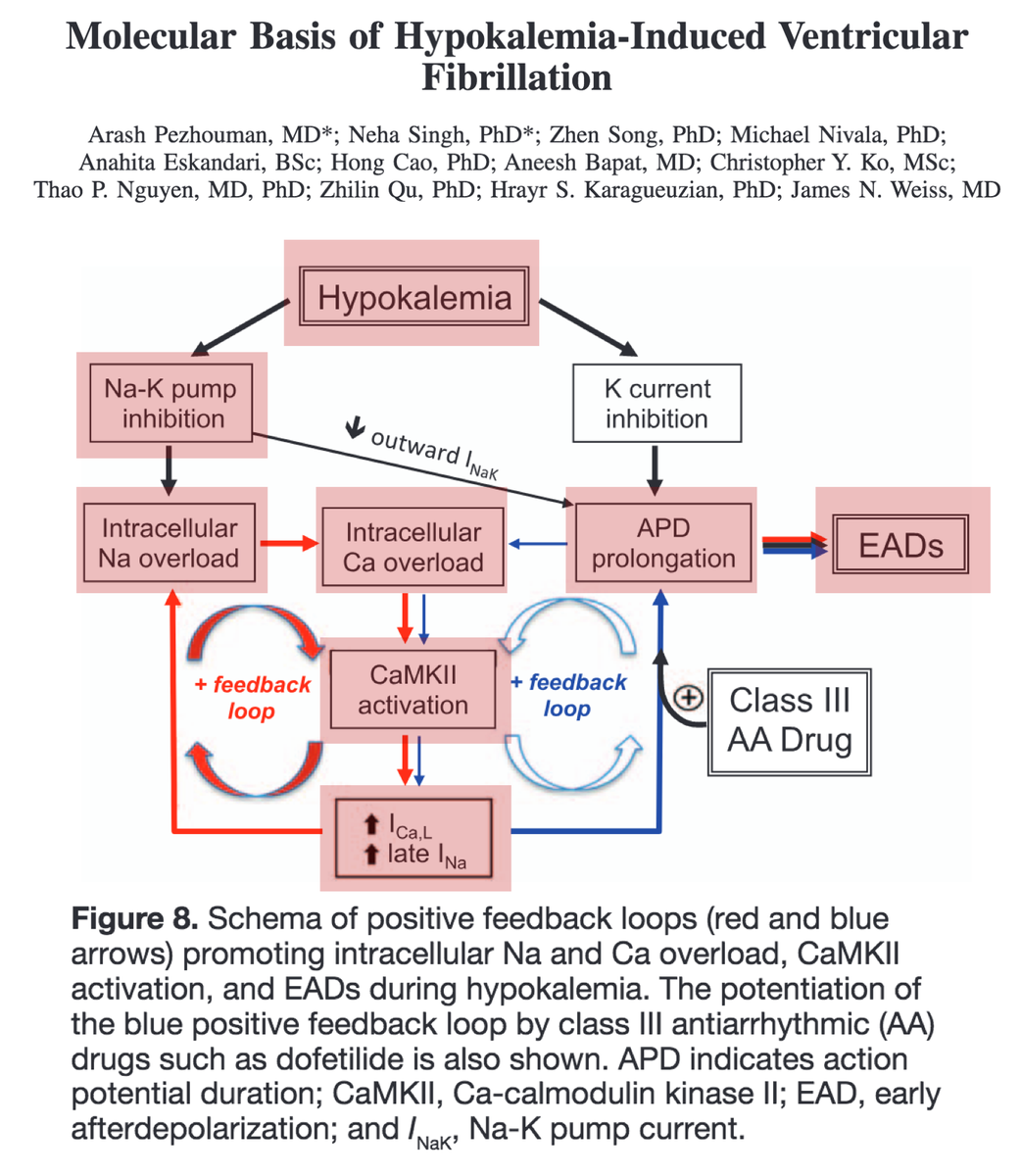

Before closing, it's worth exploring how hypokalemia might cause (or contribute) to ventricular arrhythmias. There are likely many mechanisms, but I'll concentrate on one:

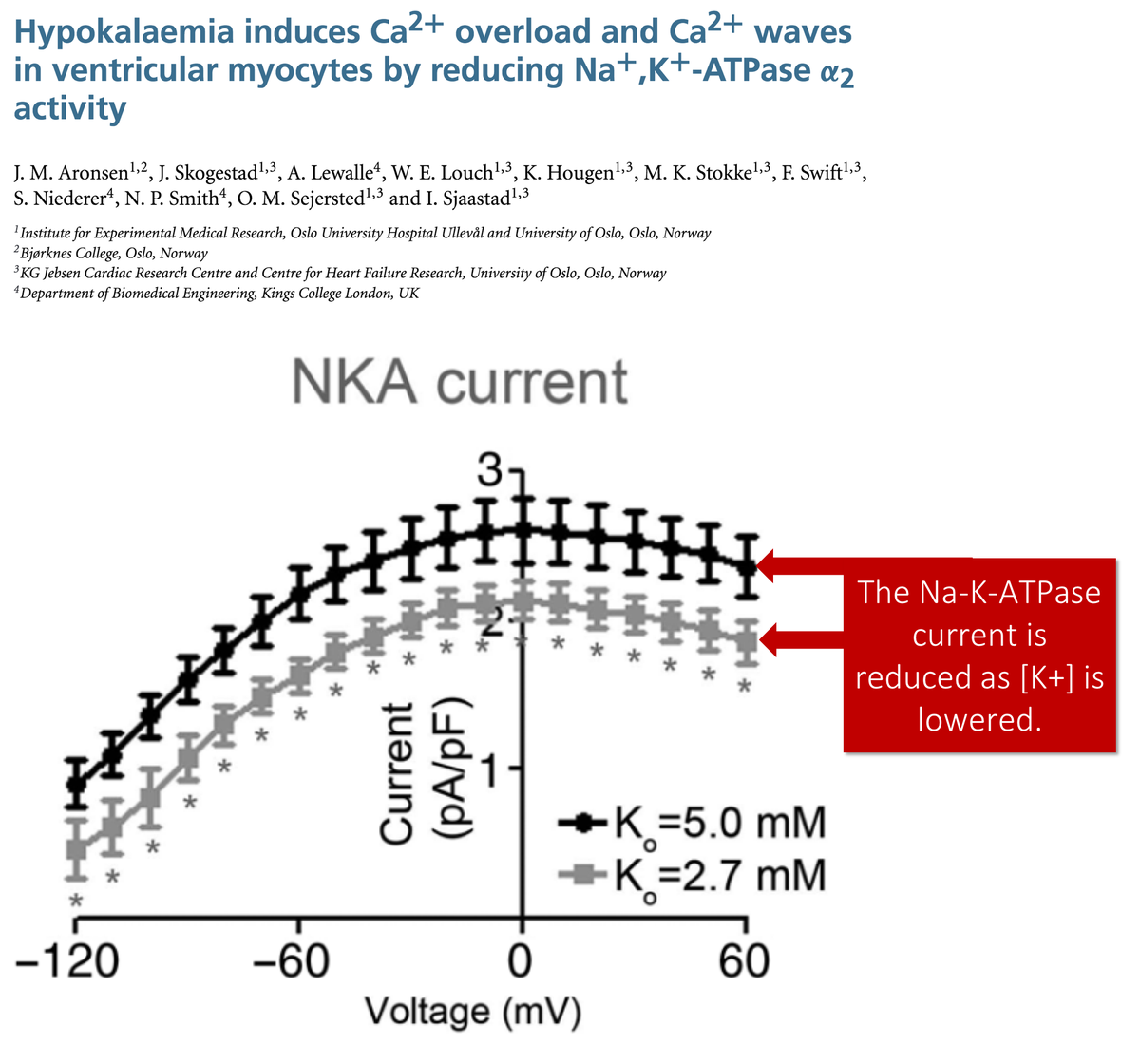

Reduced function of the Na/K-ATPase.

In rat myocytes, a reduction in [K+] from 5.0 to 2.7 mEq/L resulted in a decrease in Na/K-ATPase current of 48%.

As Na/K-ATPase function decreases, this leads to:

⬆️ intracellular [Na+], resulting in

⬇️ Na/Ca exchanger, and

⬆️ intracellular [Ca+]

ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25772299

Increased [Ca+] leads to increased Ca-calmodulin kinase II (CaMKII) activity. Eventually, this can result in early afterdepolarization-mediated ventricular arrhythmias.

The case for hypokalemia being more than an epiphenomenon is strong.

ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26269574

✔️The goal [K+] of ≥4.0 likely derived from studies of AMI

✔️3.5-4.5 mEq/L may be more appropriate in these patients

✔️Repleting all hospitalized patients to >4 is less evidence-based

✔️Hypokalemia may lead to VT/VF via the reduced function of the Na/K-ATPase