How does diabetes mellitus (DM) lead to an increased risk of infection?

I'll often hear this referenced on rounds or in morning report, but I don't recall having heard the mechanism.

As you might guess, there are many potential explanations; let's look at one of them...

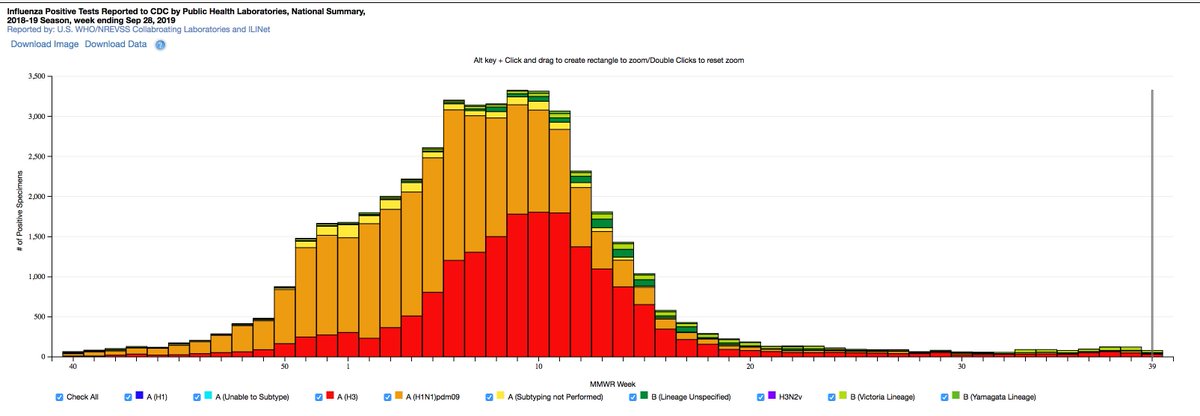

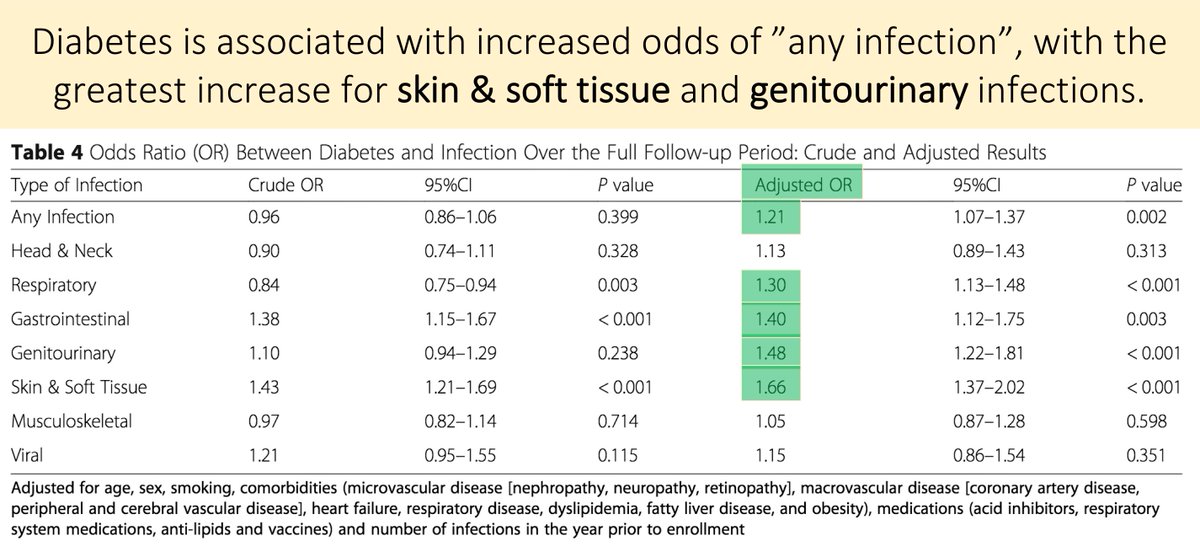

Before moving on, it’s worth establishing that there IS an increased infection risk in those with DM. Though a connection has been reported for >100 years, causality has been debated.

One 2018 calculated an aOR of 1.21 for any infection.

ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed?term=29…

While there are many factors (e.g., concomitant peripheral vascular disease and neuropathy), for this thread, I’d like to concentrate on how hyperglycemia itself impairs the immune system.

More specifically, how DM affects neutrophil function.

ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16960917

Let's ask a question.

Which of the following components of chewing gum is important for the pathogenesis of neutrophil dysfunction in patients with diabetes mellitus?

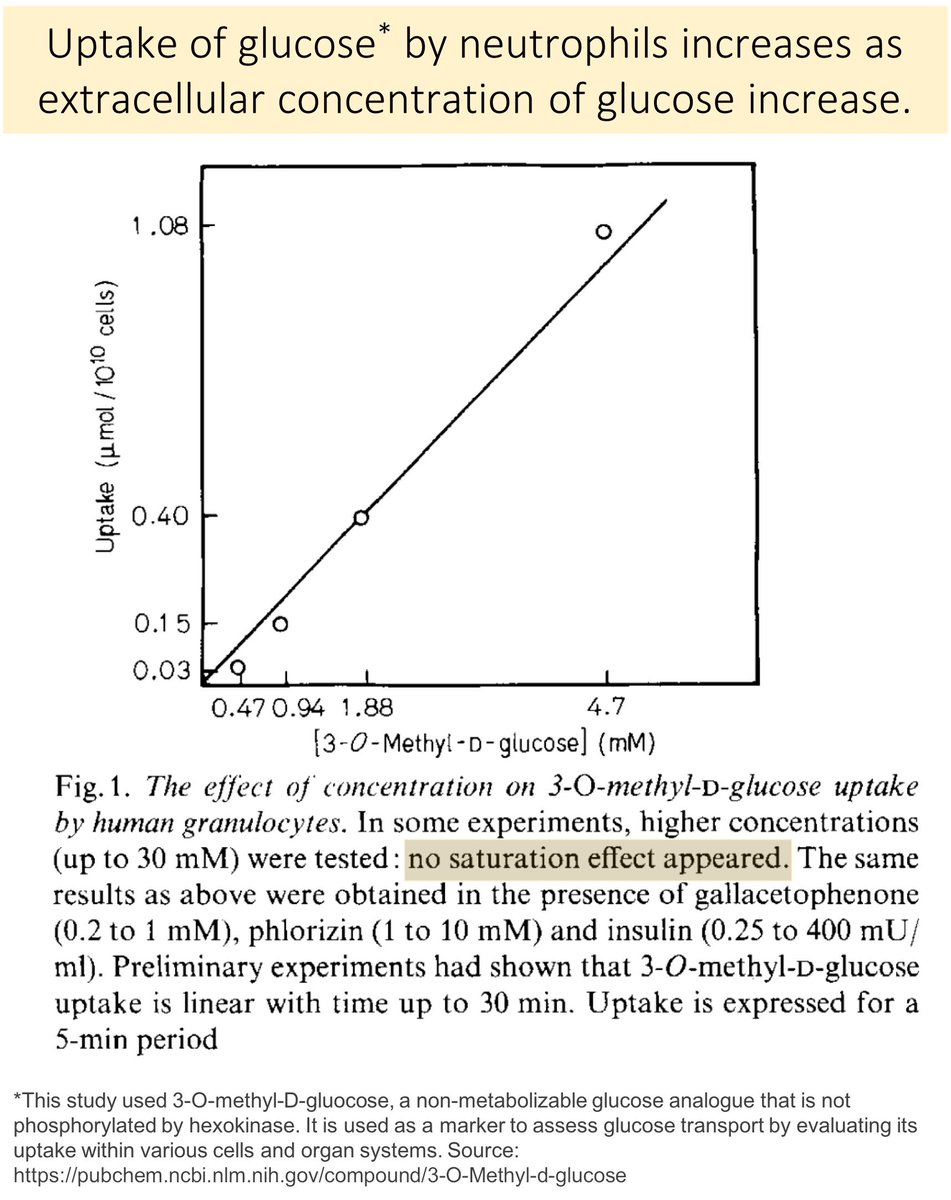

To understand the answer (sorbitol), it is important to first recall that glucose moves into neutrophils via facilitated diffusion.

As extracellular [Glu] increases, intracellular neutrophil [Glu] increases.

ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/171158

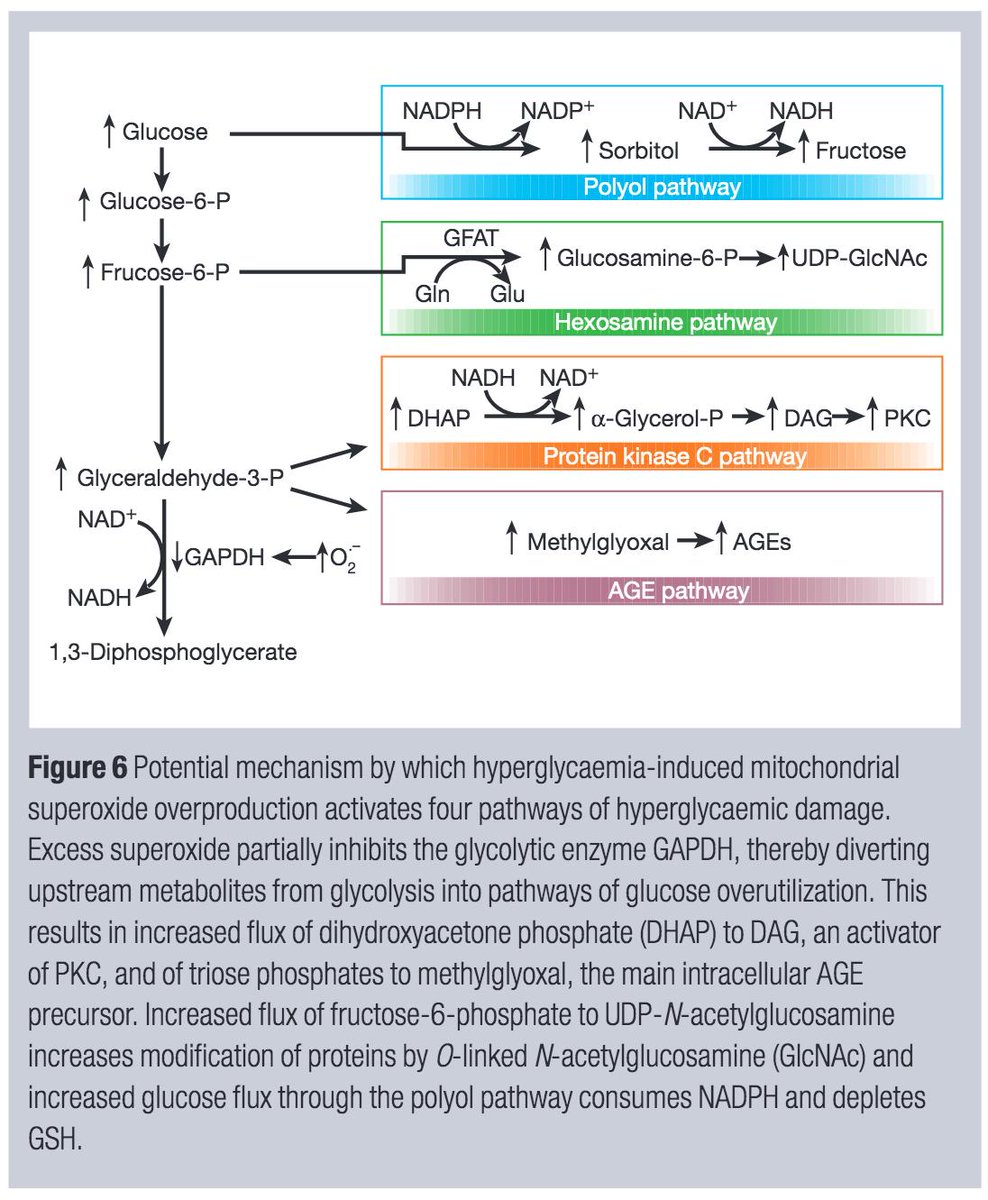

In diabetic animals, the intracellular glucose is converted to sorbitol (the first step in the polyol pathway).

Because cell membranes are relatively impermeable to sorbitol, it gets "trapped" in the cell.

ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/5907911

ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14857197

Based on the two figures in tweet 7, what would your hypothesis be for how increased sorbitol production from glucose would hinder neutrophil function?

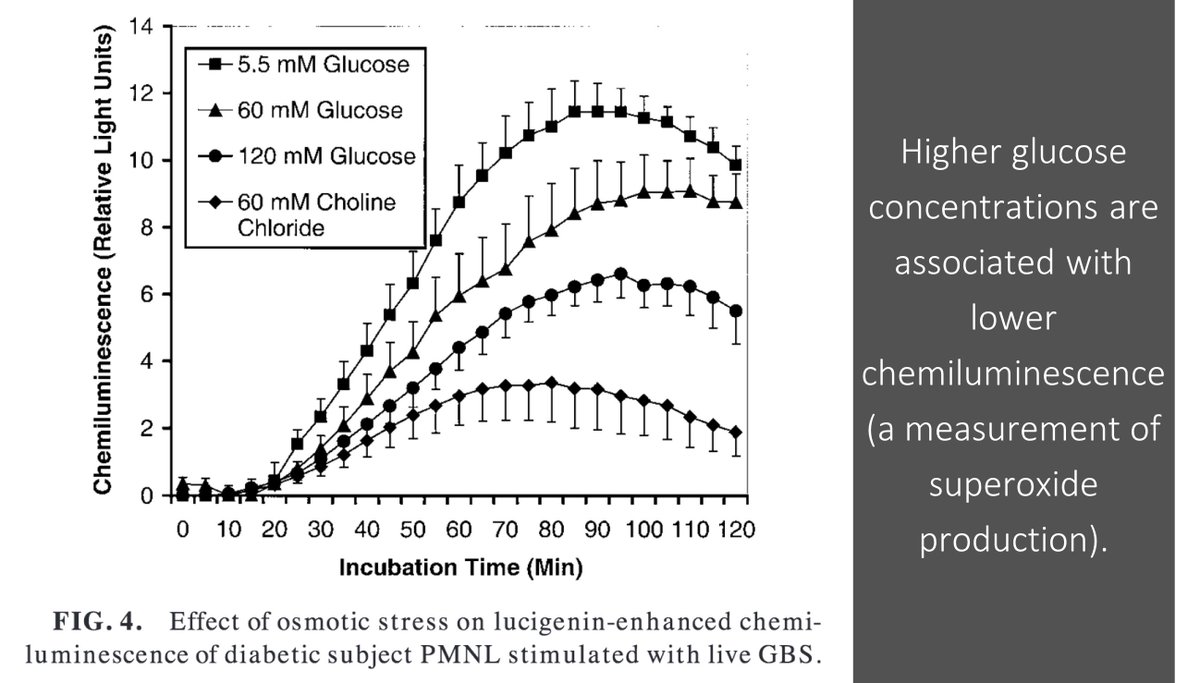

If NADPH is consumed in the production of sorbitol, less is available for the creation of superoxide (O₂⁻) utilized for bacterial killing.

This is one hypothesis for how neutrophil dysfunction might lead to increased infections in DM.

ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11461193

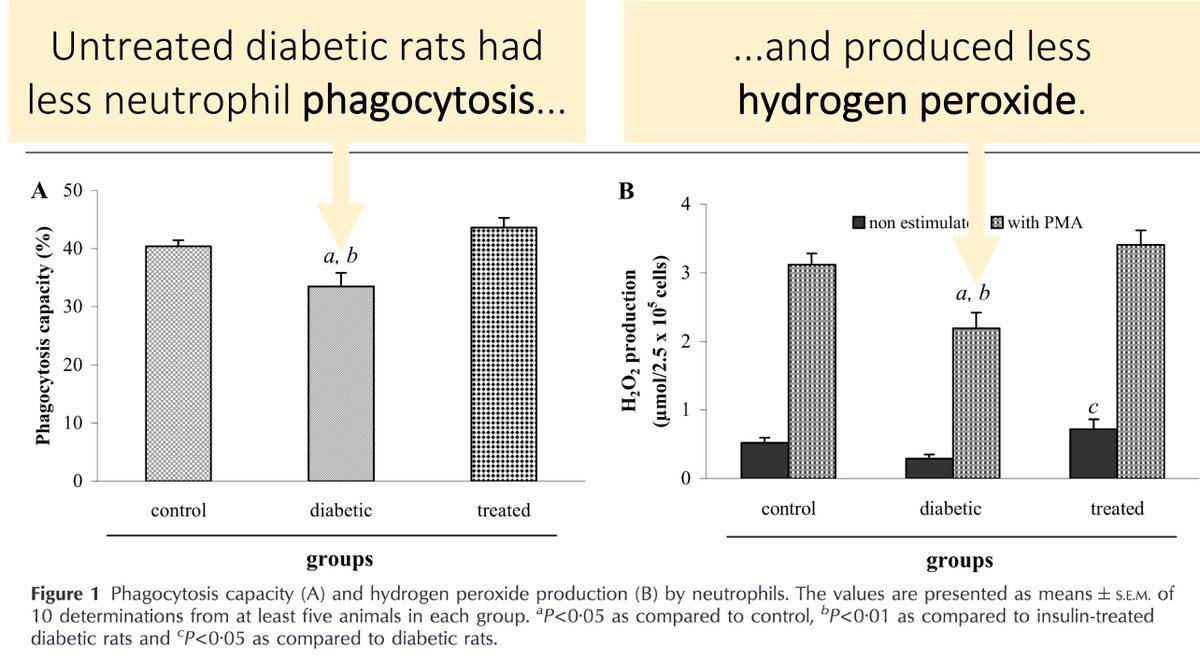

Support for this hypothesis comes from studies showing decreased phagocytosis and decreased production of hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) in rats with DM.

You'll see from tweet 7 that H₂O₂ is another reactive oxygen species made from superoxide.

ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16461555

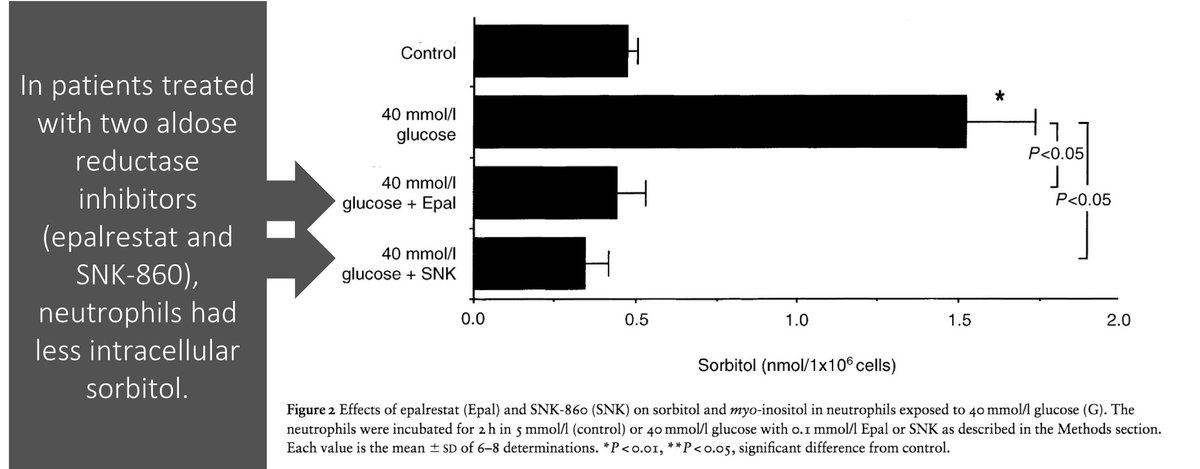

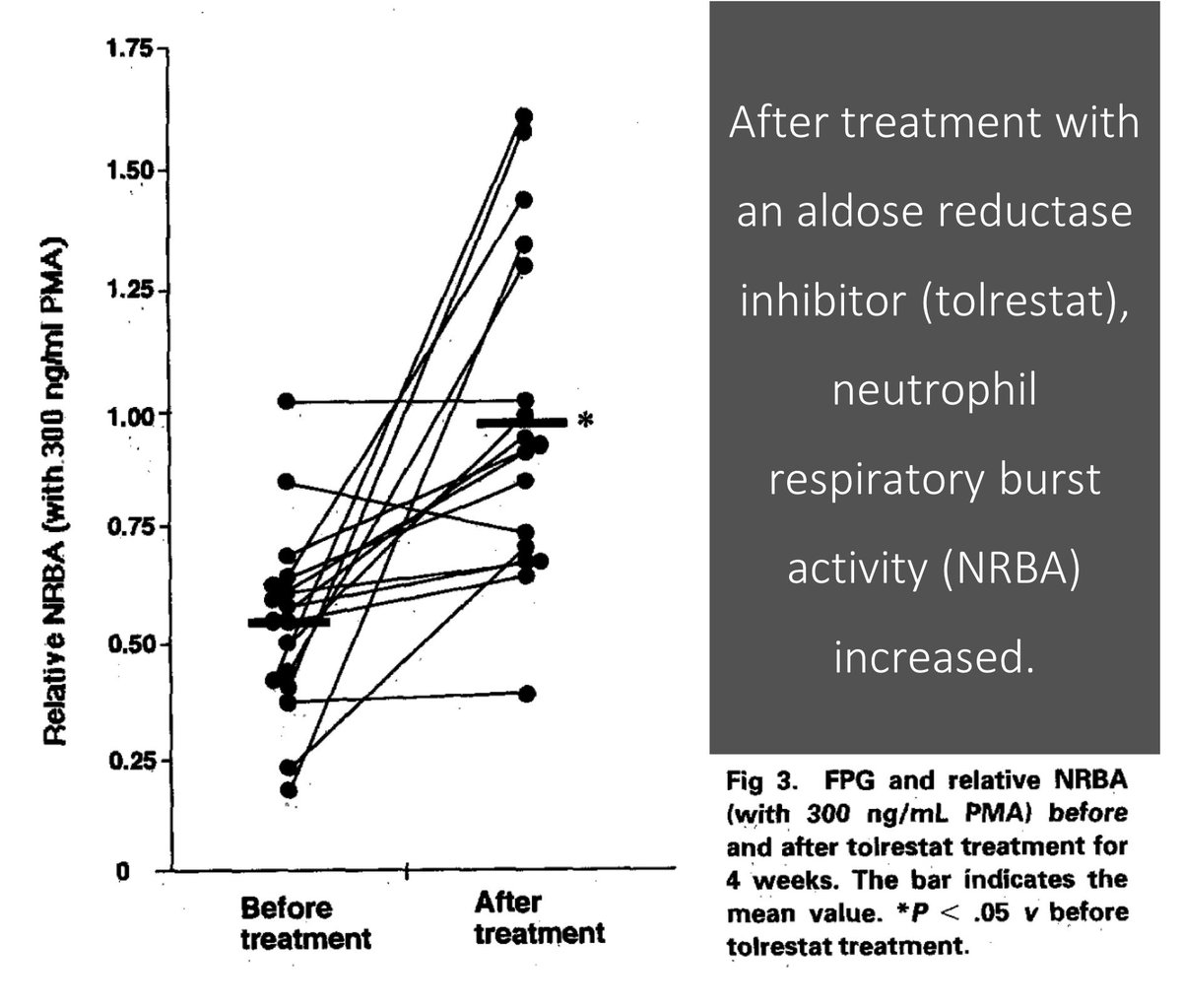

Based on the above, it should come as no surprise that aldose reductase inhibitors have been tested in patients with DM.

There is data suggesting that their use decreases sorbitol in neutrophils and increases oxidative burst.

ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10229296

ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9186297

Unfortunately, there is no data suggesting improved patient-centered outcomes related to infections with the use of aldose reductase inhibitors.

This provides a good example of why an understanding of disease mechanisms doesn't always lead to effective treatments.

Before closing, it is important to note that there are many other ways that diabetes affects neutrophils, including:

↓ adhesion and migration

↓ chemotaxis

↓ bactericidal activity

ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16461555

Another important note: many complications of DM are felt to be related to OVERproduction of superoxide. How this balance plays out in neutrophils is not clear to me.

Here is a great review of the role of superoxide in diabetic complications.

ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11742414

Now, let's ask a final question.

Which of the following would you choose to replenish, if you wanted to mitigate the neutrophil dysfunction seen in DM?

How does diabetes lead to an increased risk of infection?

➤ Glucose is converted to sorbitol, with consumption of NADPH

➤ Without NADPH, less O₂⁻ is made, potentially impairing neutrophil function

➤ Aldose reductase inhibitors haven't proved beneficial