…and its connection to the story of #Esther.

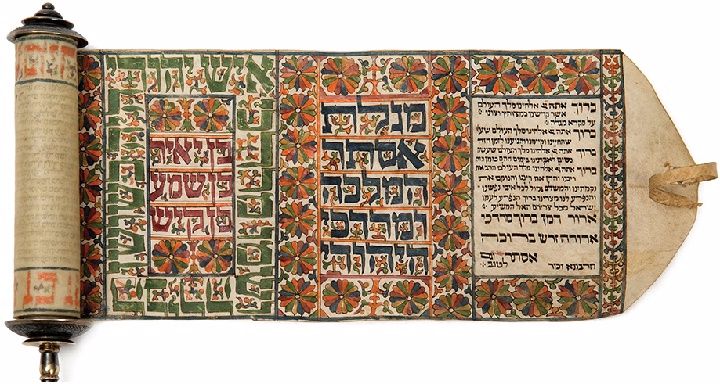

Below, a 19th cent. scroll from Iraq (cf. kedem-auctions.com),

w. blessings and curses to be read before and after in the 1st column.

Scripture isn’t a library; it’s a story—one of creation and redemption and more besides.

Intertwined within Scripture, however, are various sub-themes/stories,

which are typically defined by their intertextuality.

In the present note, we’ll consider Benjamin’s.

When Jacob first meets Rachel (Benjamin’s mother), he begins to weep (Gen. 29.11).

At first blush, his tears appear to be tears of joy.

Might they also, however, embody a deeper significance?

The last person in Scripture to ‘lift up his voice and weep’ (לשאת את קולו ולִבְכות) is Esau, who weeps because he has been tricked out of his ‘birthright’ (בכורה).

It’s hard to say. Either way, Benjamin’s story begins enigmatically.

And it continues in much the same vein.

Her relationship with Leah is a constant source of grief (Gen. 25.22 w. 30.6–8).

And, later in life, as Benjamin is born, Rachel passes away amidst ‘severe birthpains’.

With her final breath, Rachel names her son ‘Ben-Oni’ = ‘son of my travail’, yet Jacob (re)names him ‘Benjamin’ = ‘son of my right (hand)’,

Per his choice of name, Jacob keeps Benjamin at his right hand (in Canaan) while the rest of his sons head down to Egypt.

Moses sees Benjamin as ‘the beloved by YHWH’—one who is ‘sheltered by the Most High’ (Deut. 33)—, while Jacob depicts him as a ‘ravenous wolf’ (Gen. 49).

The first major event associated with Benjamin in the Biblical narrative occurs in Judges 19–20,

where a Levite and his concubine spend a (brutal) night in Gibeah.

Suffice it to say, it is one of the darkest and most horrific stories in Scripture.

And, the next day, the sun rises on the body of a dead (or near-dead) concubine, who has been raped throughout the night.

Consequently, at the conclusion of Judges 20, we find the people of Israel assembled at Shiloh,

Benjamin’s line is about to be erased from history, and the voice of Rachel is about to ring out once again.

Or so it seems.

But the men of Israel devise a ‘solution’ to preserve Benjamin’s line.

It involves a yearly feast at Shiloh, further abuse of women, and the desolation of Jabesh-Gilead. Yet it does enable the tribe of Benjamin to live on.

Against the backdrop of Judges 19–20 (from a canonical perspective), the story of Samuel begins to unfold.

It opens in a grimly familiar manner, i.e., with a yearly feast at Shiloh, tears (בכה) in Ramah (cp. 1 Sam. 1.1, 7),

It therefore seems as if Samuel’s story will follow the trajectory of Gibeah’s (Judg. 19–20).

But, mercifully, it does not.

and the tide of male violence in Judges is hence stemmed by a godly woman.

Soon afterwards, light begins to dawn in Israel.

and Ramah becomes a place of justice (7.16–17) (at least for a while).

And, next, Saul arises.

The question is whether Saul will continue the good work begun by Samuel or go his own way.

In 1 Samuel 9–31, we find out.

Although the rise of Saul is greeted with enthusiasm by the Israelites, it has unmistakably sinister undertones.

Like the Benjaminites of Judg. 19–20, Saul is introduced to us as a Gibeahite warrior of significant renown.

Saul is introduced to us in a highly ambiguous light.

Yet Saul is at the same time associated with a dark and violent history.

Will Saul follow in the footsteps of Samuel or cause further tears in Ramah?

Was Gibeah’s problem its lack of a king (cp. Judg. 21) or will the selection of a king from Gibeah turn out to be a problem in its own right?

Just as the Levite of Judges 19 makes an awful decision when he decides to lodge in Gibeah (Saul’s hometown) rather than Ramah (Samuel’s), so the Israelites make an awful decision when they choose Saul over Samuel,

Samuel is the man Israel should have asked for—which explains the rather unusual statement Hannah makes in 1.20,

Note: The events of 1 Sam. 9 do not represent the last time Israel enter into a covenant with Sheol (cp. Isa. 28.15).

Saul’s reign is mass of contradictions.

In the course of it, Saul rejects Israel’s priesthood, chief prophet, and (replacement) king.

The first to be cast off is the priesthood.

Saul instead elects to officiate over Israel’s sacrifice himself, and goes on to align himself with a deposed priesthood (the sons of Ichabod: cp. 14.1ff.).

Saul’s rebellion is likened to the sin of ‘witchcraft’ (1 Sam. 15), which is exactly what Saul ultimately turns to (at En-Dor: cp. 1 Sam. 28).

Saul becomes insanely jealous of David’s success.

While he refuses to slay Agag (who is handed to him on a plate), Saul is happy to travel the length and breadth of Israel in his bid to slay David.

It is a sad and tragic end to a life of great potential,

As Saul loses popularity, David gains it.

David also, ironically, begins to act like a Benjaminite and to fulfil a number of the prophecies associated with Benjamin.

While Saul is unable to sleep, David dwells in security (ישכן לבטח: Psa. 16) per the promise vouchsafed to Benjamin (Deut. 33.12).

which resonates with Moses’s prophecy in Deut. 33.12, where Benjamin is referred to as ידיד יהוה = ‘the beloved of YHWH’.

Benjamin is born en route to Bethlehem, which foreshadows the way in which Saul the Benjaminite’s kingship is transferred to David the Bethlehemite (cp. Gen. 49.10).

Isaiah describes the fall of twelve cities, at least half of which are closely associated with Saul—viz. Ai, Migron, Michmash, Ramah, Gibeah, and Nob (10.28ff.)—,

In sum, then, Saul dramatically fails to make amends for the Gibeahites’ sins.

Redemption must arise from another place. And, happily, it does.

At the outset of the book of Esther, an age-old foe arises against Israel. The foe in question is Haman.

Haman is a foe whose rise Saul should have prevented, since Haman’s origins can be traced back to Agag the Amalekite.

Note: Below is a midrashic ‘translation’ of Esther (image from thetorah.com) with an extra portion of Mordecai’s ancestry written in the top margin...

But, happily, they soon begin to diverge.

While Saul lets his power go to his head, Esther uses her power with great wisdom.

Meanwhile, Esther arranges a similar sequence of feasts, at which she turns Ahasuerus’s anger against her enemy, Haman,

Consumed by hatred, Haman’s behaviour becomes progressively more extreme...

...until he finds himself prostrate on the ground at the feet of a woman whom he has previously terrorised, overcome by fear and anxiety.

Furthermore, while Saul is not permitted to take Agag’s spoils yet disobediently does so (and thrice proclaims his innocence in the matter: 1 Sam. 15.13, 15, 20),

But, as wonderful as they may be, Esther’s actions do not constitute a full reversal of Saul’s failures,

since the consequences of Saul’s failures go beyond an unvanquished foe.

And, in the context of the Biblical narrative, that enmity is not laid to rest until a later Benjaminite rises to power: the apostle Paul.

Both men are Benjaminites and have the same Hebrew name.

And both men set themselves against Israel’s Messiah and his people.

But, for all the similarities between Saul and Paul’s live, the two men end up in very different places.

And so, like his ancestor Benjamin, Paul becomes the lastborn of ‘the twelve’ (1 Cor. 15).

For a start, Paul inherits aspects of the young Saul’s character.

No longer is his behaviour characterised by pride and self-ambition.

and replies with prudence and modesty when his authority is called into question (e.g., 1 Cor. 4, 9).

he recognises what Jesus the Messiah has done for him and hence knows he is ‘beloved of YHWH’ (cp. Gal. 2.20 w. Deut. 33.12).

And, as a result, Paul’s life will never be the same.

No longer does Paul act like one of the ‘ravenous wolves’ about whom Jesus warns his disciples (cp. λύκοι ἅρπαγες in Matt. 7.16).

not by means of a second chance or a fresh start, but by means of a personal and transformative encounter with the risen Messiah.

THE END

Please Re-Tweet. #Purim2020