Do robots destroy jobs and cause mass unemployment?

No, they don’t!

Happy to share that our paper

“The Adjustment of Labor Markets to Robots”

has been accepted for publication in the Journal of the European Economic Association.

Here’s a little thread about it. (1/18)

No, they don’t!

Happy to share that our paper

“The Adjustment of Labor Markets to Robots”

has been accepted for publication in the Journal of the European Economic Association.

Here’s a little thread about it. (1/18)

It’s been a long journey – starting in Sept. 2017, when we first published this widely read @VOXEU column (the older ones on #Econtwitter might still remember).

And here we are, four years later, with the final version #JEEA: drive.google.com/file/d/1dNv9lb…

voxeu.org/article/rise-r…

And here we are, four years later, with the final version #JEEA: drive.google.com/file/d/1dNv9lb…

voxeu.org/article/rise-r…

The paper received in media attention in >25 countries.

A personal highlight was my double interview @faznet with popstar philosopher Richard David Precht, where I argued that his claim – robots cause mass unemployment – is, well, not true. /3

faz.net/aktuell/wirtsc…

A personal highlight was my double interview @faznet with popstar philosopher Richard David Precht, where I argued that his claim – robots cause mass unemployment – is, well, not true. /3

faz.net/aktuell/wirtsc…

I won’t do the usual summary thread of methods & findings – please read the paper 😉

Instead, I'll focus on just one (potentially policy-relevant) aspect: how have German labor markets handled big transformations in the past? Maybe as a guide for the future. /4

Instead, I'll focus on just one (potentially policy-relevant) aspect: how have German labor markets handled big transformations in the past? Maybe as a guide for the future. /4

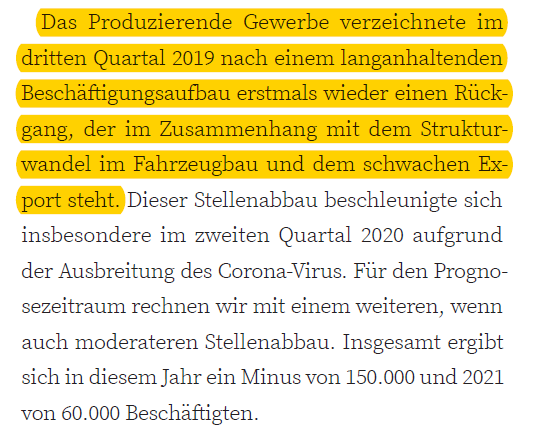

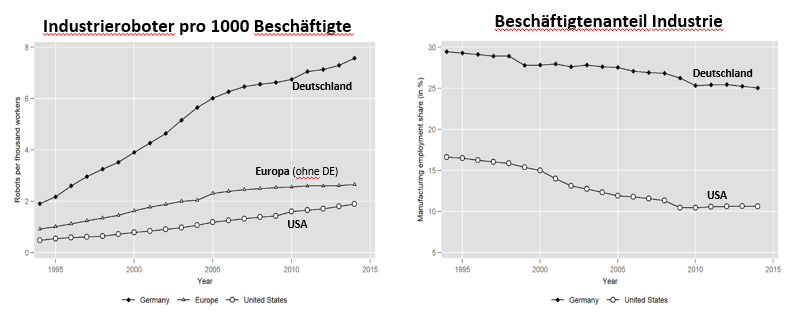

Starting in the 1990s, robots entered German manufacturing.

This has led to displacements of tasks. Many production steps previously carried out by humans, such as the assembly of cars, were now entirely performed by robots. /5

This has led to displacements of tasks. Many production steps previously carried out by humans, such as the assembly of cars, were now entirely performed by robots. /5

Obviously, this has raised *many* concerns about technological unemployment

But our key finding is that firms did *not* fire those displaced workers. Instead, they retained & retrained (most of) them, and the majority ended up performing new & more complex tasks on their jobs /6

But our key finding is that firms did *not* fire those displaced workers. Instead, they retained & retrained (most of) them, and the majority ended up performing new & more complex tasks on their jobs /6

I.e., the same guy who used to bolt cars was turned into a maintenance, software, marketing… person.

Sure, firms could have fired the car screwers, and looked for young specialists to fill the new jobs. But they decided differently, and went for “firm-specific human capital” /7

Sure, firms could have fired the car screwers, and looked for young specialists to fill the new jobs. But they decided differently, and went for “firm-specific human capital” /7

Was that voluntarily? Sure, but with a twist.

We find evidence that the ret(r)aining strategy was chosen more often in regions with higher density of union members. That probably reflects some sort of deal between management and works councils... /8

We find evidence that the ret(r)aining strategy was chosen more often in regions with higher density of union members. That probably reflects some sort of deal between management and works councils... /8

Like: “Ok, we hang on to the old guys, but then you moderate your future wage demands”. This stabilized jobs for incumbents

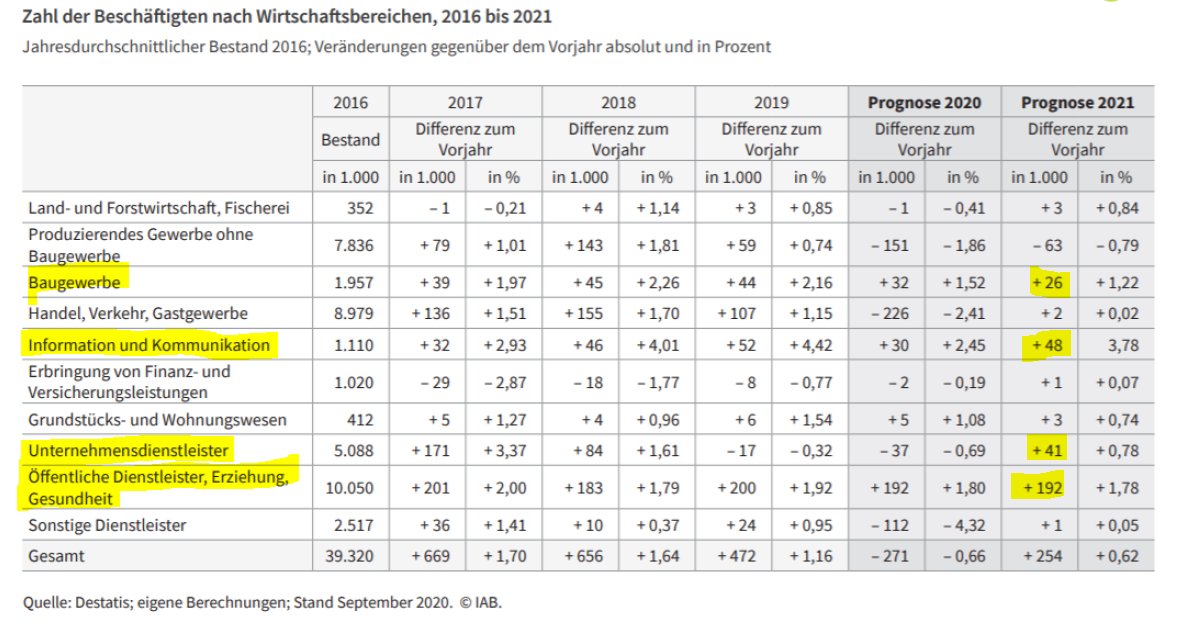

At the end, Germany seems to have digested the rise of the robots better than the US, despite the fact that 🇩🇪 is *much* more robotized than 🇺🇸 /9

At the end, Germany seems to have digested the rise of the robots better than the US, despite the fact that 🇩🇪 is *much* more robotized than 🇺🇸 /9

In a related paper, @DrDaronAcemoglu and Pasqual Restrepo find that robots caused severe job and wage losses in the American “hire&fire” labor market.

No such thing in 🇩🇪 - thus, the corporatist German model has apparently delivered pretty well. /10

voxeu.org/article/robots…

No such thing in 🇩🇪 - thus, the corporatist German model has apparently delivered pretty well. /10

voxeu.org/article/robots…

Another positive news is what happened to the young generation in Germany in response to the robots.

Since firms mostly went for the ret(r)aining of old incumbents, this meant that fewer new factory jobs were created in the manuf sector. /11

Since firms mostly went for the ret(r)aining of old incumbents, this meant that fewer new factory jobs were created in the manuf sector. /11

Young entrants, thus, had to start their careers elsewhere. And they did! Mostly in business-related services at comparable starting wages.

We even find that young students, in anticipation of all the changes, responded to the “robot shock” by investing more in education. /12

We even find that young students, in anticipation of all the changes, responded to the “robot shock” by investing more in education. /12

The unlucky ones were those incumbents for whom the ret(r)aining strategy did not play out, possibly because they worked for relatively weak, non-robotized firms that lost market shares.

Read more about it in this follow-up paper /13

voxeu.org/article/robots…

Read more about it in this follow-up paper /13

voxeu.org/article/robots…

Now, what could all of this mean for the future?

Obviously, quite massive transformations are ahead in many industries, in manuf and beyond.

No longer from robots, but from other digital technologies, and from the need to reduce carbon emissions. The concerns are similar. /14

Obviously, quite massive transformations are ahead in many industries, in manuf and beyond.

No longer from robots, but from other digital technologies, and from the need to reduce carbon emissions. The concerns are similar. /14

What will happen to workers who currently produce combustion engines, or parts thereof? What will happen to small cities like Kirchheimbolanden, whose local economy depends heavily on just one firm that happens to produce Diesel turbochargers? /15

rheinpfalz.de/lokal/donnersb…

rheinpfalz.de/lokal/donnersb…

.@Fraunhofer claims that the total number of jobs in the new, green car industry will be roughly the same as today.

But it will be very different jobs: less bolting of turbochargers, more customer-services for self-driving electric vehicles etc. /16

isi.fraunhofer.de/de/themen/elek…

But it will be very different jobs: less bolting of turbochargers, more customer-services for self-driving electric vehicles etc. /16

isi.fraunhofer.de/de/themen/elek…

On a positive note, our robot paper raises the hope that German manuf could manage this transformation in a similar, non-disruptive fashion. But for this to work, on-the-job training and education will probably be crucial elements.

We’ll see if this works out. /17

We’ll see if this works out. /17

For the time being, we’re very happy that our paper has landed in a nice journal such as #JEEA, and we hope you’ll enjoy reading it.

And remember it the next time you see headlines such as theses ones 🤖

And remember it the next time you see headlines such as theses ones 🤖

PS: A side remark. One reason why it took almost 4y is that we tried different journals before.

My favorite response from #Referee2 was: "oh yeah, your results are really interesting and convincing, but they are specific to the German case. What can we learn from it?" 😐

My favorite response from #Referee2 was: "oh yeah, your results are really interesting and convincing, but they are specific to the German case. What can we learn from it?" 😐

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh