en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ecologica…

commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Jule…

netleland.net/hsampa/mansoes…

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Belgo_Bui…

New Urbanism’s ideal was modeled as a “transect”, which is a concept borrowed from ecology.

transect.org/transect.html

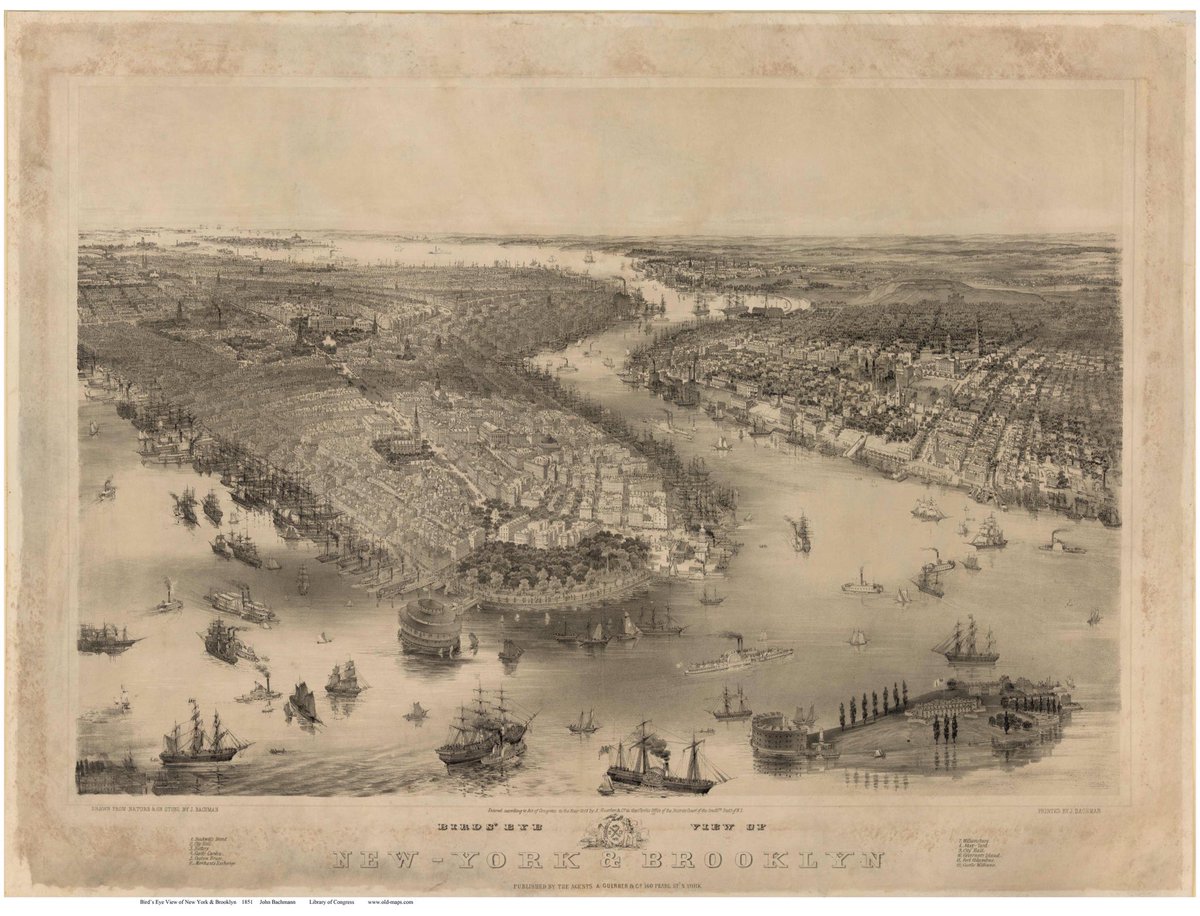

It models transitions from one community to another as a sequence of distinct geographical layers.

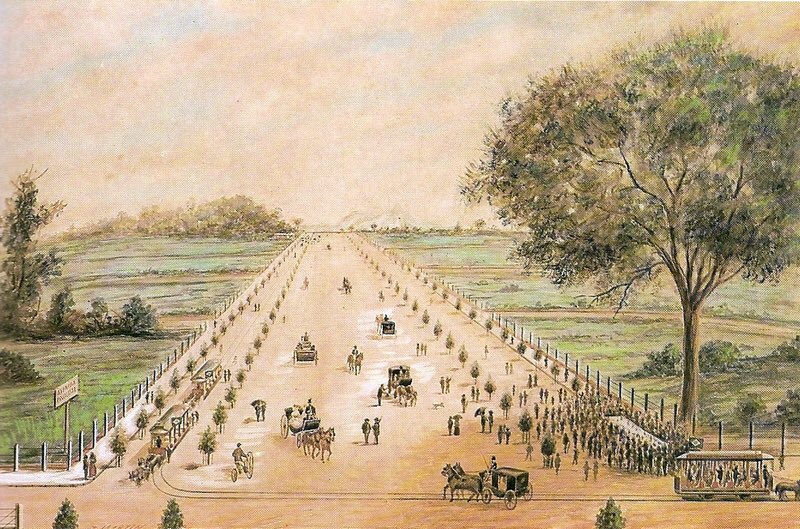

It tried to shortcut its own model, going from T2 to T4-5 without first going through T3.

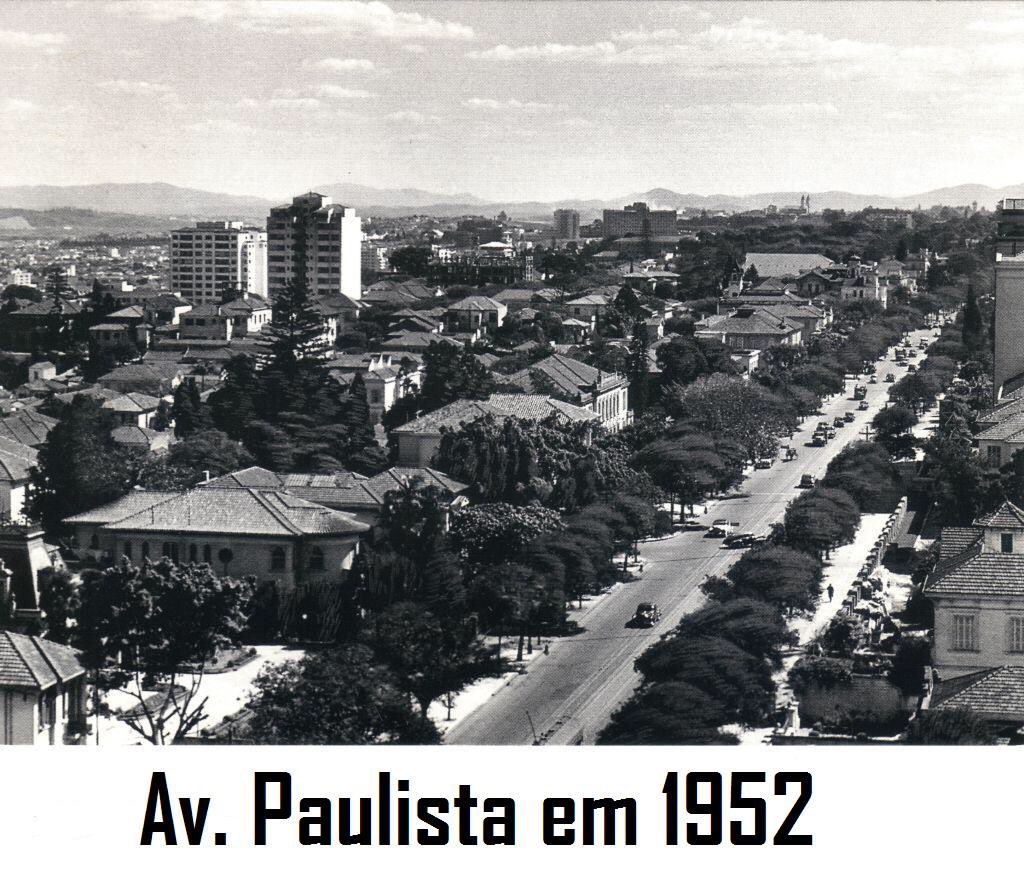

What needs to be added to the transect is the vertical axis of time.

This future needs to be invented.

This is where “accessory dwelling units” get their importance.

Should neighborhoods change?

NIMBYs and anti-gentrification activists agree that they should not. The modern planning system was invented to enforce that agreement.

We need energy-efficient transit, but we’re stuck with weedy urban growth that can’t sustain it.

The problem is our urban planning has no concept of lifecycle.

granolashotgun.com/2019/03/04/mar…