New #COP26 analysis: 🚨🌡️🌍

Is COP26 on track to keep 1.5°C alive?

Here I connect the dots between findings of the most recent scientific reports and look at what current pledges mean for carbon budgets limiting warming to 1.5C

(1/n)

Is COP26 on track to keep 1.5°C alive?

Here I connect the dots between findings of the most recent scientific reports and look at what current pledges mean for carbon budgets limiting warming to 1.5C

(1/n)

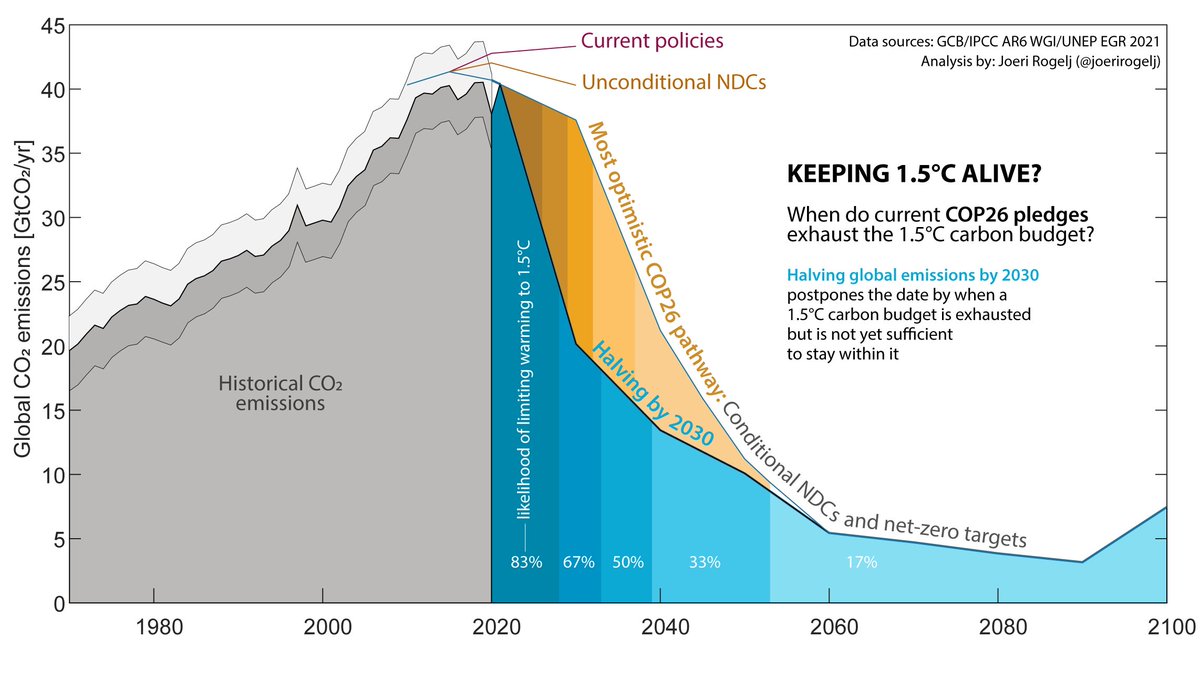

I start with historical CO2 emissions from the Global Carbon Project @gcarbonproject as assessed in the latest @IPCC_CH #AR6 #ClimateReport

About 2400 billion tonnes of CO2 (GtCO2) have already been emitted between the years 1850 and the end of 2019 (2/n)

About 2400 billion tonnes of CO2 (GtCO2) have already been emitted between the years 1850 and the end of 2019 (2/n)

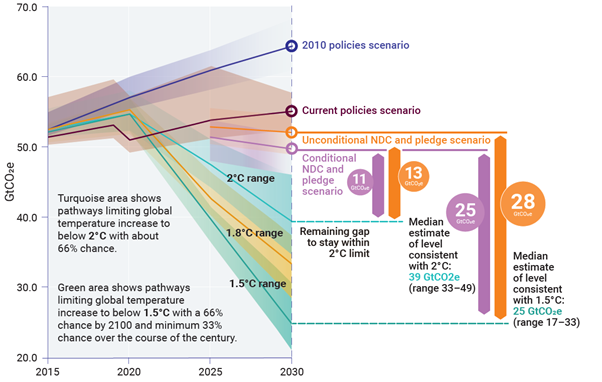

I then add global emissions pathways consistent with current policies, and various interpretations of country pledges (called NDCs, or nationally determined contributions) from the latest update of the @UNEP #EmissionsGap Report 2021. (3/n)

wedocs.unep.org/bitstream/hand…

wedocs.unep.org/bitstream/hand…

The lowest, most optimistic pathway assumes that all conditions that countries include in NDCs are met, and all #NetZero are achieved.

(Note: the @UNEP report highlights that few 2030 targets are in line with meeting countries' long-term net zero targets at this stage) (4/n)

(Note: the @UNEP report highlights that few 2030 targets are in line with meeting countries' long-term net zero targets at this stage) (4/n)

For the remainder of the analysis, I only work with this lowest, most optimistic pathway.

And compare the emissions under the curve with the remaining carbon budgets for limiting warming to 1.5°C from the latest @IPCC_CH AR6 #ClimateReport

(5/n)

ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg1/

And compare the emissions under the curve with the remaining carbon budgets for limiting warming to 1.5°C from the latest @IPCC_CH AR6 #ClimateReport

(5/n)

ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg1/

As it stands today, under the most optimistic pathway of #COP26 pledges and announcements, the carbon budget for keeping warming to 1.5°C with 50% or higher chance will be exhausted by the early 2030s.

(6/n)

(6/n)

What can be done?

What about increasing near-term ambition to ensure emissions are halved by 2030?

This postpones the date and is critical to keep 1.5°C alive, but action (and emissions reductions) cannot end there.

(7/n)

What about increasing near-term ambition to ensure emissions are halved by 2030?

This postpones the date and is critical to keep 1.5°C alive, but action (and emissions reductions) cannot end there.

(7/n)

Only when further combined with the achievement of #NetZero CO2 emissions by 2050 can total CO2 emissions be kept to within a 1.5°C carbon budget.

Even then the likelihood that warming is kept to 1.5°C is barely about 50%. Not great, but keeping 1.5°C alive!

(8/n)

Even then the likelihood that warming is kept to 1.5°C is barely about 50%. Not great, but keeping 1.5°C alive!

(8/n)

Uncertainties in past emissions, interpretations of pledges, and the size of carbon budgets do not change the core message that ambition needs to be increased to keep 1.5°C alive. (end)

With a big thank you to @RobinLamboll for helping to calculate these pathways!

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh