Hello #twitterstorians! Sorry about the break for the last two days. There were...uh...technical difficulties...

But we're back! In this thread, I, @StevenMVose, want to give a brief #history of the #Delhi Sultanate and share some facts and recent scholarly takes that may complicate the #narrative of the Sultanate, and of #Islam in So. Asia, that I alluded to in the previous thread.

I will also highlight some #Jain interactions with the Sultans, which suggest a complex set of interactions between #Indian religious communities and the emerging #Islamicate "state" in the late 13th and early 14th c's. CE

The Delhi Sultanate was not a single polity but rather a series of five dynasties that ruled varying amounts of #India between 1206 and 1526 CE, reaching its height between 1326 and 1334, when Jinaprabhasūri was in Muhammad bin Tughluq's court.

But let's start by backing up a bit and taking stock of the advent of Islam and #Muslims in South Asia, and then think about the problematics of calling it "Islamic Rule."

Before any military engagements, Arab Muslim traders regularly traveled to India. The earliest mosque there is in #Kerala, claimed to have been built in 629 CE (three years before the Prophet Muhammad PBUH died).

At the dawn of the 8th c., India was ruled by numerous small kingdoms. Muslim traders In 711/2 CE, Muhammad bin Qasim, an Arab, led the conquest of #Sindh. This marks the first rule by a Muslim king in South Asia.

Muslim rulers of the region regarded the local Hindu population as "ahl al-dhimma." The Sun (Aditya) Temple in Multan, e.g., was allowed to carry on with worship and hosting pilgrims, dividing ⅓ of the revenue (keeping ⅔). Reversing course, Ismailis destroyed it in 986.

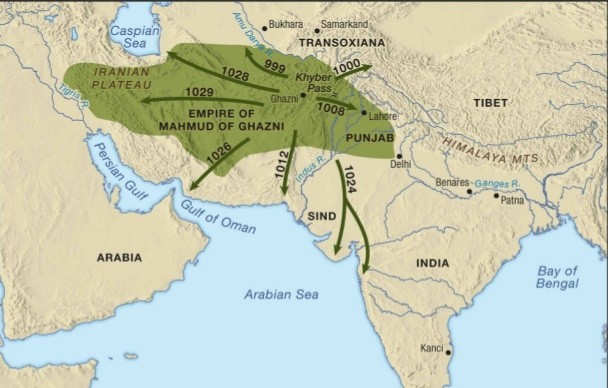

In the early 11th c., Mahmud of Ghazni, an Afghan, launched a series of plundering raids in India. However, he had no interest in ruling in India; he used the plunder to pay his armies for his westward aspirations.

Mahmud "famously" plundered the #Somnath Temple on the coast of peninsular Gujarat in 1024/5. #Persian sources claim that he carried the linga back to Ghazni. However, the wooden temple was restored quickly and a stone temple was constructed a century later (see photo).

In fact, no #Hindu sources note this sacking. Persian narratives suggest this event, along with his campaign against the Ismailis in Multan, helped Mahmud to gain an investiture from the #Abbasid Caliphate, which granted him the title of "Sultan" - the first to use it.

In his 1333 "Chapters on Various Pilgrimage Places" (VTK, Ch. 17), Jinaprabhasūri notes that in 1081 VS (1024/5 CE), "Gajjaṇa" attacked the temple.

The story of Mahmud's desecration came into Indian public consciousness in the 19th c., as #British colonialists deployed divide-and-rule tactics in the wake of the 1857 #SepoyRebellion, portraying it as evidence of Muslim antagonism against Hindus and #Hinduism.

Now for the main event. Between 1175 and 1192, another Afghan empire, the Ghurids, waged several campaigns against N. Indian kingdoms, finally defeating #Prithviraj Chauhan in 1192. Led by Mu'izz al-Din Muhammad, they established a permanent base in Delhi.

After Muhammad's assassination in 1206, his Mamluk (slave) General, Qutb al-Din Aybak declared independence from the Ghurids. This marks the beginning of the Delhi Sultanate.

Establishing their capital on the grounds of "King Prithviraj's Fort" (Qila Ra'i Pithora), one of their first tasks was to set up a Jama mosque. The Qubbat al-Islam (Dome of Islam) was built from parts taken, acc. to its inscription, from some 27 Hindu and Jain temples.

While temple parts were clearly used with faces effaced, expediency and conquest were likely the motivating factors. Quarrying new stone takes time; the same area of the temples was used for the mosque; and not all temples in the area were destroyed.

Until 1290, a series of Mamluk generals became sultans. They controlled much of N. India and the Ganges River.

In 1290, the Khaljis, a Turkish-Afghan family, ascended to power. Though short-lived, this dynasty would become the benchmark for future Sultans. Ala' al-Din (r. 1296-1316) launched a series of campaigns that greatly expanded the Sultanate, establishing a vast empire.

Although colonial and modern historians cast his conquest in religious terms and modern legend calls him "The Bloody" (Khuni), Ala' al-Din's army consisted of Hindu infantry (paiks) and disaffected Mongol generals.

They were also equal opportunity plunderers, taking equally, for example, from Hindu, Jain and Arab merchants in Cambay (modern Khambhat, Gujarat). This plunder and territory helped the Khaljis maintain a large army that fended off several #Mongol invasions.

The Khalji army launched campaigns in western India in 1298-1310, which brought many Jains into the Sultanate state. In 1313, a Jain temple at #Shatrunjay was plundered and the main image broken.

Several Jain sources note that the local governor, Alp Khan (d. 1316) worked with a Jain layman, #Samara Shah, to restore the temples and images in 1315.

Ala' al-Din employed Hindus and Jains to important positions. Thakkur Pherū, a Jain, held a high position in his mint, where he authored a number of #Apabhramsa works on #coin alloys ("billons"), #gemmology, and mathematics. He served the #Tughlag court, too. (See SR Sarma)

The Tughluqs succeeded the Khaljis in 1320. Muhammad (r. 1325-1351) expanded the empire to its greatest extent, holding more territory than any Indian empire since #Ashoka's Mauryan Empire (321-185 BCE).

I’ll be back in a few hours to talk more about the reign of Muhammad bin Tughluq. Preview: everything you know about him is wrong. Goodnight!

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh