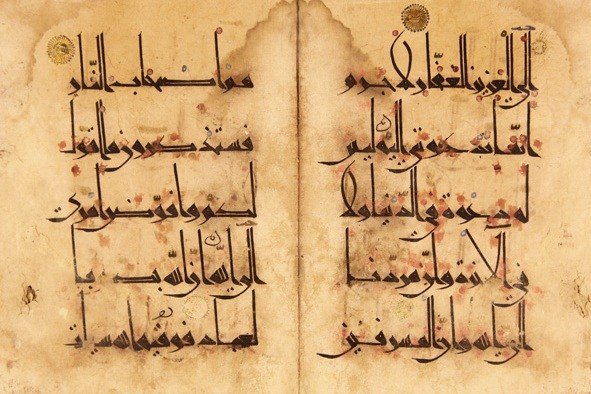

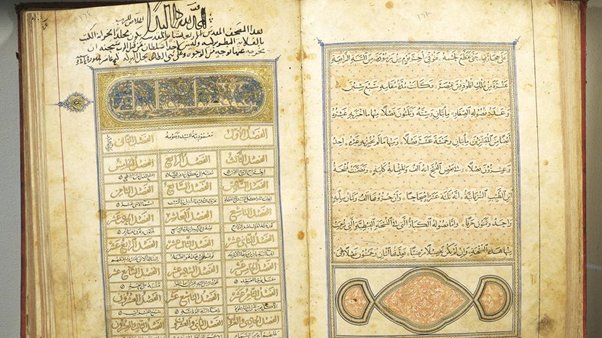

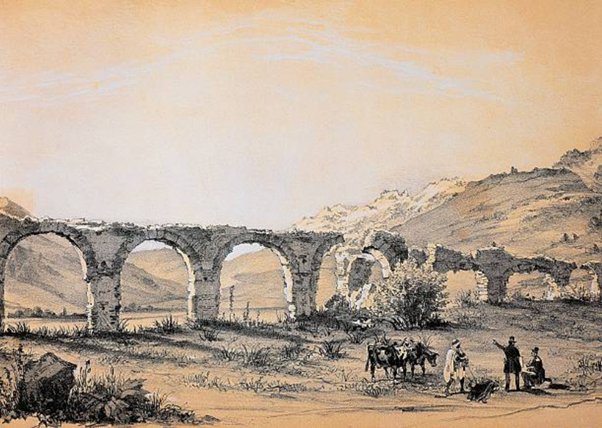

So here's the story of how a tiny fragment from the opening of ancient poems became one of the most enduring poetic tropes in history: that of "stopping by the ruins"

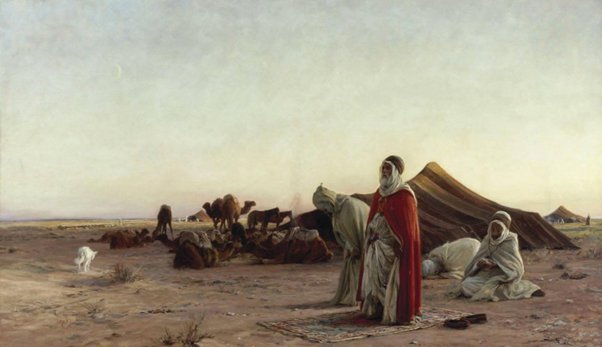

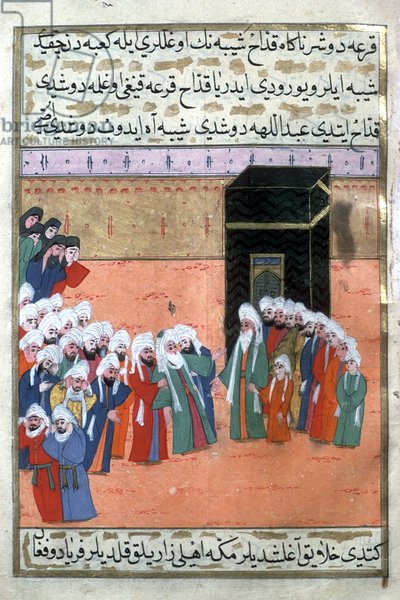

This beautiful motif originates in the pre-Islamic period, & occurs continuously in the history of Arabic poetry.

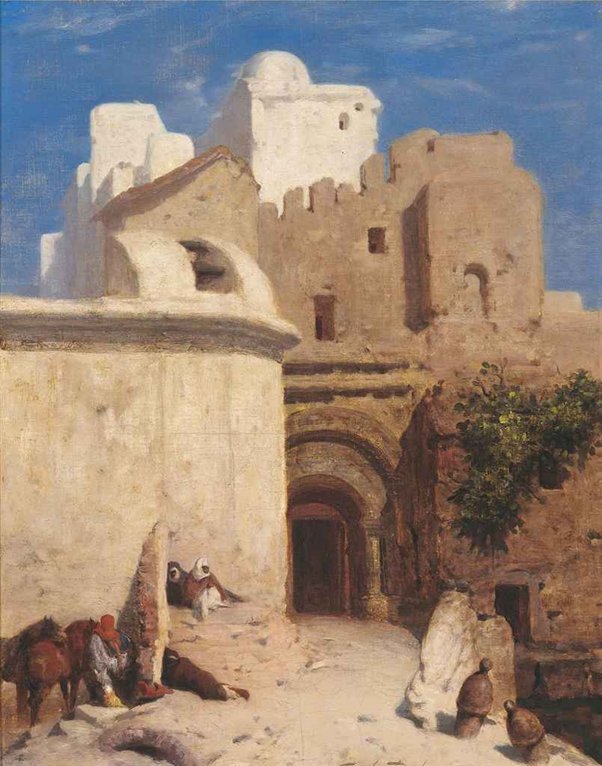

The word wuquf / وقوف holds the double meaning of standing & stopping, so this portion of the poem usually forms a moment of stillness & meditation, outside of time.

Poets sometimes returned to it at the end, but not always.

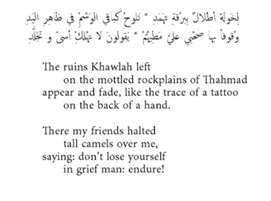

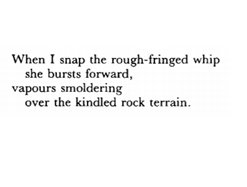

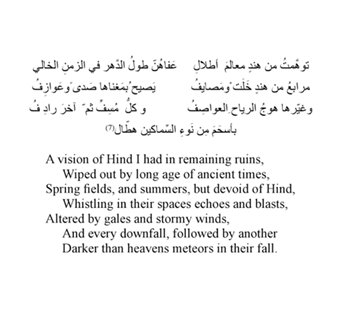

Tarafa’s Mu’allaqa poem opens with ruins appearing on the horizon like an apparition.

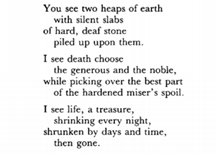

Here landscape & memory become one: the ruin becomes a repository for memories that can be accessed by spending a moment of stillness there

For Tarafa, the ruins around him are reminders of the cruelty of fate & the indiscriminate passing of time. They speak of life’s injustice & the inevitability of loss.

scholarship.haverford.edu/cgi/viewconten…

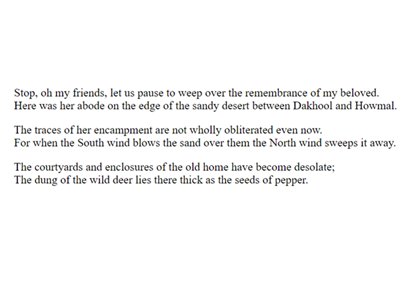

He opens by describing the desolate place, broken and overgrown by nature.

And read it in English here: sacred-texts.com/isl/hanged/han…

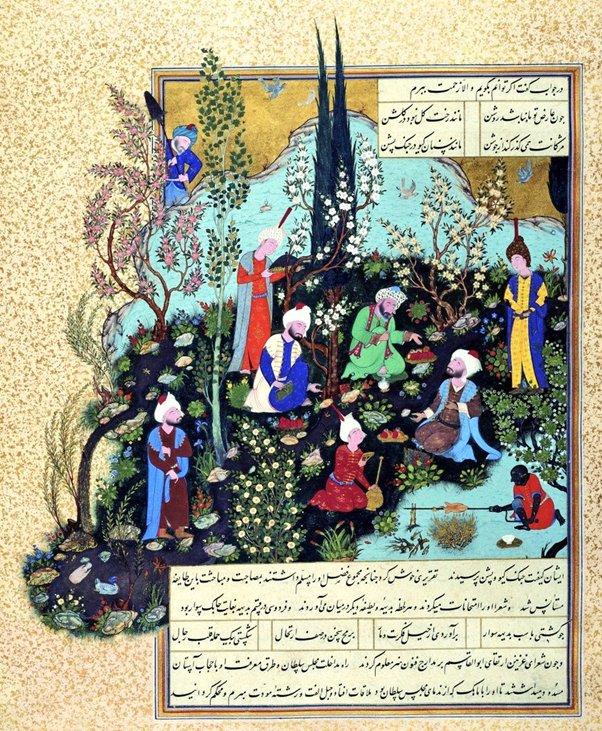

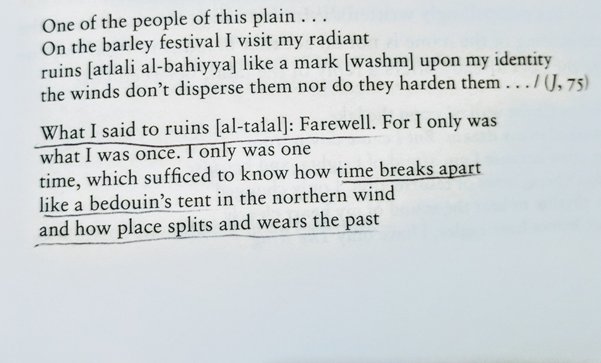

Just as European poets have rewritten & adapted epics like the Odyssey, so have modern Arabic poets returned to these odes.

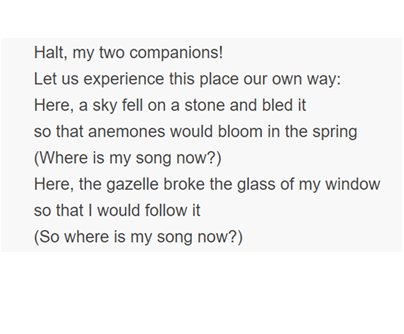

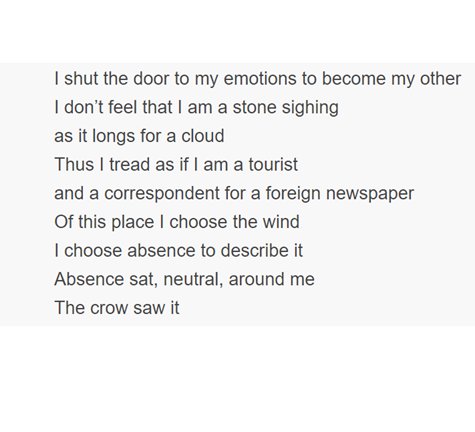

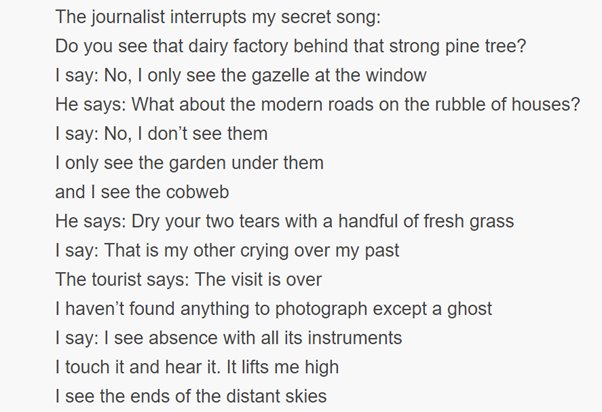

His poem “Standing Before the Ruins of Al-Birweh” is only one example (trans. @sinanantoon) of the motif finding new life: jadaliyya.com/Details/23789/…

In 1948, when Darwish was 7, the village was depopulated of its Palestinian inhabitants after it was captured by Israeli forces.

In the ruins of his former village, the memories of his childhood resurface, just as the medieval poets saw memories of their lost loves.

“It was a citadel of my imagination that has collapsed,

Pour me a drink and let us drink of its ruins”

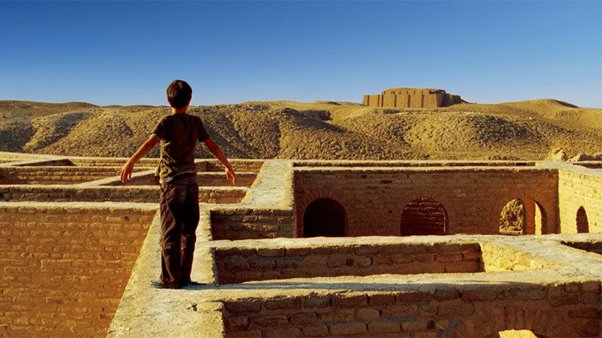

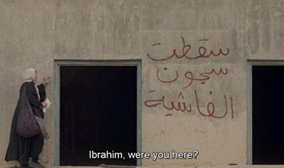

In 2010, the award-winning Iraqi film Son of Babylon (ابن بابل) by director Mohamed al-Daradji made heavy use of the motif, having characters wander through Iraq’s ancient ruins & its modern ones alike.

The film tells the story of a young boy, Ahmed, who is trying to find his father after the 2003 US invasion.

They search the ruins, trying to find any trace of him. But instead of finding bittersweet memories there, they find only absence & pain, a loss without redemption.

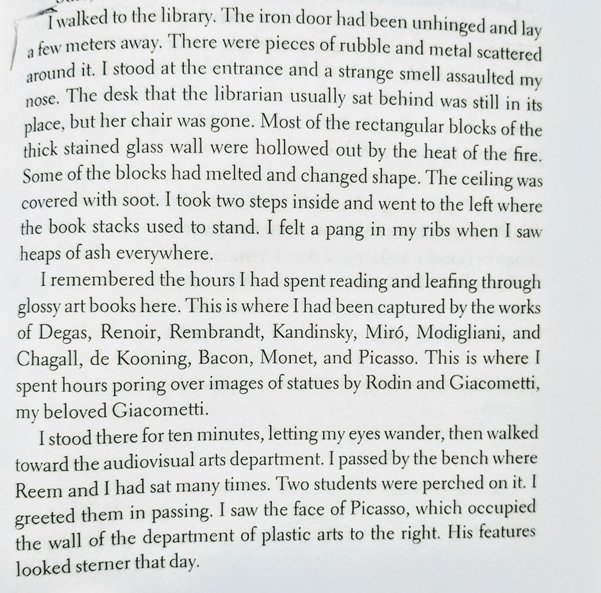

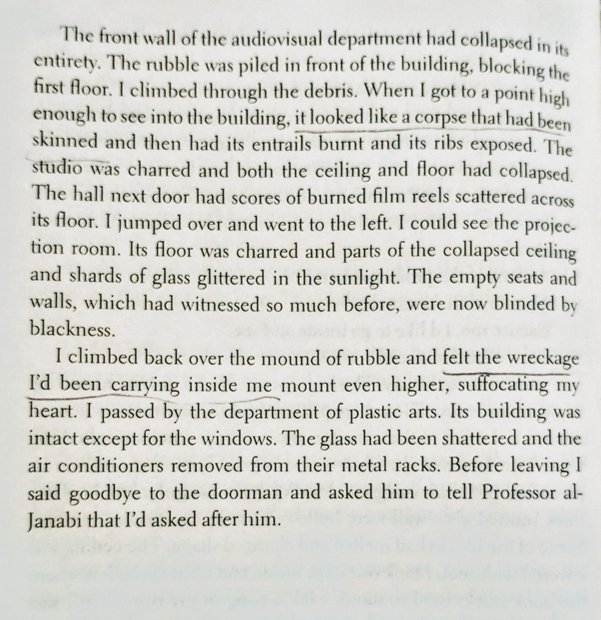

To take just one example, in his novel The Corpse Washer (وحـدهـا شـجـرة الـرمّـان), Iraqi author Sinan Antoon has a character wander through the ruin of the Baghdad National Library, & remember.

The ruins of Baghdad are human & bodily, “like a corpse”.

The bodies & souls of the people, conversely are like ruins: “the wreckage I’d been carrying inside me mount[ed] even higher”.

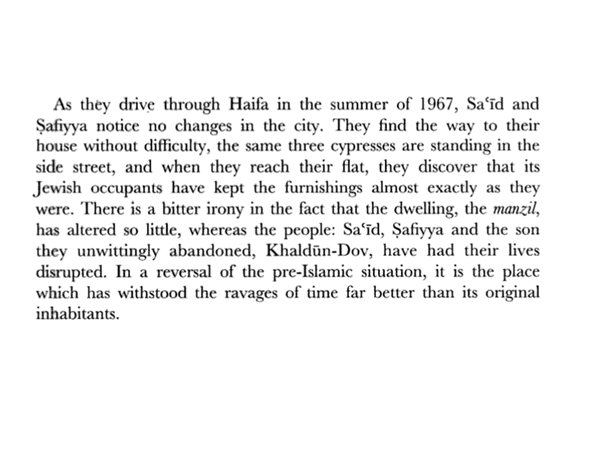

Hilary Kilpatrick describes how one Palestinian writer, Ghassan Kanafani, turns the motif on its head in his 1969 novel 'Ai'd ila Haifa (Return to Haifa).

From the earliest days of the Bedouin poets to the battlefields of modern neo-imperialist wars, it has expanded to become a whole way of reacting to loss & memory.

If there are any ruins in your area, go stop by them today & see what memories they bring up! But don't lose yourself in grief...