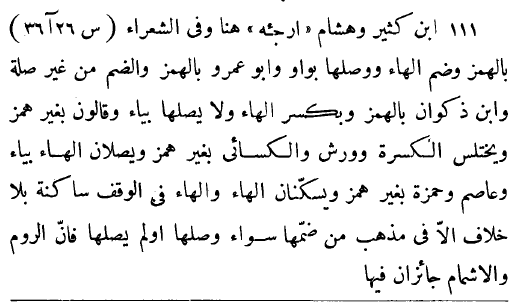

A thread with annoyances:

Owens oversimplification obscures and misrepresents this.

(I also don't understand why he uses a modern commentary on the didactic poem based on the Nashr, rather than, you know, just use the Nashr).

This type of ʾimālah is very interesting:

Others (like al-Farrāʾ) do recognise this ʾimālah and its an ancient retention of a contrast from Proto-Arabic.

arabianepigraphicnotes.org/journal/articl…

(where I don't actually mention al-Kisāʾī, which is honestly a little silly, but I was just getting into that material at the time).

ʾAbū ʿAmr has much more limited ʾimālah, bizarre to call it regular.

Rawm is the replacement of a final vowel /u/or /i/ with ultrashort [ŭ] or [ĭ]. It cannot apply to qāla, since it ends on /a/.

This can thus only be done if the vowel was /u/.

nquran.com/ar/ayacompare/…

Where he got the idea from that rawm is the labialisation is utterly unclear to me.

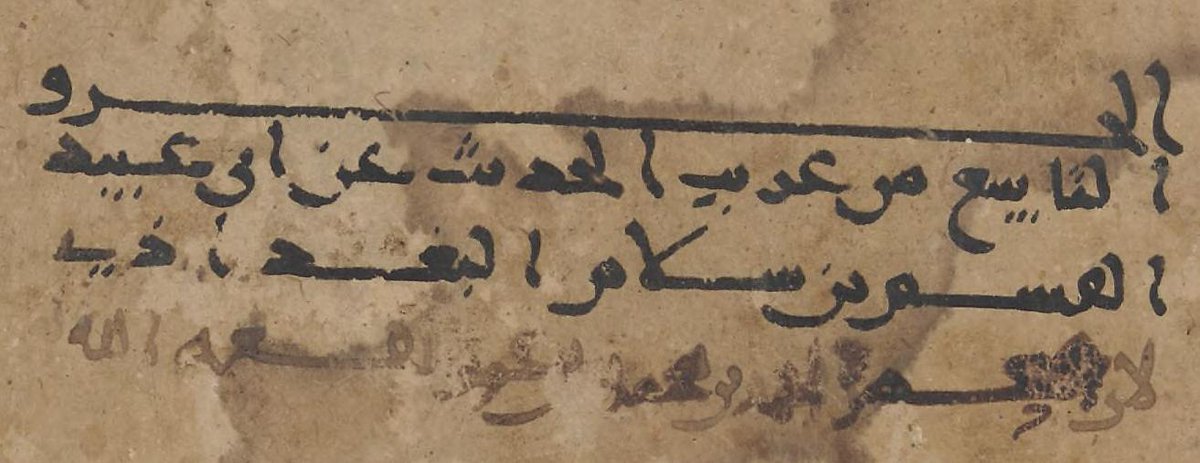

qāla lahum, yaqūlu lahū, bi-l-bāṭili li-yudḥiḍū

ʾidġām: qāllahum; yaqūllahū; bilbāṭilliyudḥiḍū

+ʾišmām: qāllahum; yaqūlʷlahū; bilbāṭilliyudḥiḍū

+ rawm: qāllahum; yaqūlŭ lahū; bilbāṭilĭ liyudḥiḍū

ʾišmām likewise increases, adding an audible reflex of /u/.

Idġām reduces the most distinctions.